The Rise and Fall of RITA GORR (1926 – 2012)

(All photos courtesy Suzanne Geirnaert, Freddy Verschaffel and Charles Mintzer)

1. THE RISE

(Rita second from left between her mother and deceased brother)

(Rita second from left between her mother and deceased brother)

Rita Gorr was born in Zelzate, a small industrial town to the north of Ghent (official name in Dutch = Gent). Her father, a plasterer, had left Ghent for a new job in Zelzate. Jules Geirnaert and his wife Maria Lambrechts had an older son who died at his birth. Another brother died at 33 from cancer. Her younger sister Suzanne (Suzon) was born in 1930. Gorr was baptised Marguerite Philomène, two Christian names with more than a French ring to it. This was quite normal at the time. The bourgeoisie in Flanders preferred to speak French (or something that resembled it and was often a ridiculous literary translation of their local Dutch) and common people often followed that example when giving names to their children. Remember that when she was four years of age the state university of Ghent finally switched to Dutch; 100 years after the Brussels mutiny that created “le royaume de la belgique” and due to a racist attitude - still nowadays representative for the speakers of le belge (the walloon language that resembles French somewhat)- Flemings were finally allowed to study in their own language at a university. Those far gone days of social ostracism of Flemings in their own country had quite an influence on Gorr as we shall see later on. When the family moved back to Ghent she was six years of age. At the time Ghent shopkeepers in the centre and the better suburbs often refused to speak Dutch or they pretended not to understand it. So did almost all employers, industrialists, merchants etc. (Nowadays French is almost a dead language in Flanders, not spoken anymore and detested by pupils who no longer want to lose time studying it). But 80 years ago young Rita knew, as did all Flemish working class children, the importance of foreign languages (which would be so important in her later career). On the other side they often neglected their own language which they thought they already knew. Up to her last days Gorr would perfectly speak her local Ghent dialect but always had some difficulties in using correct and modern Dutch which would cause some embarrassing situations in later life. Gorr’s French pronunciation in singing was perfect and only a linguist could hear from her spoken French that it was not her native language. Moreover the Dutch speaking countries never had the parochial outlook typical for France, Germany, Britain or the US. Nobody ever thought of dubbing the immensely popular movies during the thirties and up to now all movies, documentaries and sitcoms on TV are still broadcasted in the original language with subtitles. That meant Gorr at an early age was exposed to foreign languages, especially French, English and German. Moreover Gorr had four years to practice that last language. She was fourteen when the Germans overran the country. Movies were soon exclusively German; radio often broadcasted German language snippets in all kinds of programmes and there was a steady stream of orders, instructions and judgements in German (with translation in Dutch which is a Germanic language too). It was a time of sorrow, poverty and oppression but with one advantage: French, British, American and Italian singers often had difficulties in learning German roles Gorr took far less time to master the Wagner libretti.

(at age two and her communion)

(at age two and her communion)

Gorr was a very fine pupil at elementary school. Better off children started high school at twelve but for most working class children elementary school lasted till they were fourteen and then they started their working life. Gorr, due to several child illnesses, was fifteen when she completed her eight years of elementary school. For a short time she hoped to become a nurse but the family didn’t have the money to pay for courses and uniforms and moreover Rita Geirnaert was faint-hearted when she saw blood. By 1941 German occupation extortion rose steeply to keep the “Vaterland” quiet and cosy and living standards plummeted all over Flanders.

(at her graduation)

(at her graduation)

Fifteen years old Rita Geirnaert had to look for a job. She found one with the Lecompte family in Sint-Amandsberg, nowadays a suburb of Ghent. The Lecompte’s were wealthy, educated and cultured and they were French, coming from Lille (Rijsel in Dutch): for hundreds of years the capital of the French speaking part of the historical county of Flanders which was lost when Louis XIV conquered the city. They were looking for a maidservant and Rita Geirnaert got the job. In his badly researched biography French writer Georges Farnet says Gorr didn’t speak a single word of French until her sixteenth but this is simply not true. The family wouldn’t have engaged a servant who couldn’t understand their orders. Gorr was the classical maidservant of those days. Running courses, cleaning, cooking, washing all kinds of things (often in ice cold water) and looking after the children. In the evening she had to retire to a small room in the attic; Moreover there is a well founded story that Monsieur Gustave demanded some other services as well as was not unusual in a relationship between boss and maidservant in those lean times. Gustave Lecompte was a teacher of music and he was the first who heard something in the voice of his maidservant when she sang some ditties for his children or when she sang along with radio. Later on Gorr herself said she had a small pretty soprano voice which sounded somewhat like French chansonnière Rina Ketty. Monsieur Gustave mentioned his maidservant’s talent(s) to his brother Félicien who took an interest as well in the girl. He was a producer of his own perfumes which he sold in a shop in one of the fine streets in the Ghent Centre. Félicien Lecompte agreed to finance the young girl’s musical studies in exchange for some services as well. One is reminded of Battista Meneghini’s financial support during the first months of his discovery of American soprano Mary Callas in exchange for those same services. There are some differences as well. After all Callas was 24 at the time, an adult and not a teenager, Meneghini was not married and only 26 years older while Monsieur Félicien was married and had three children. He was born in 1890 and therefore thirty-six years older than his protégée.

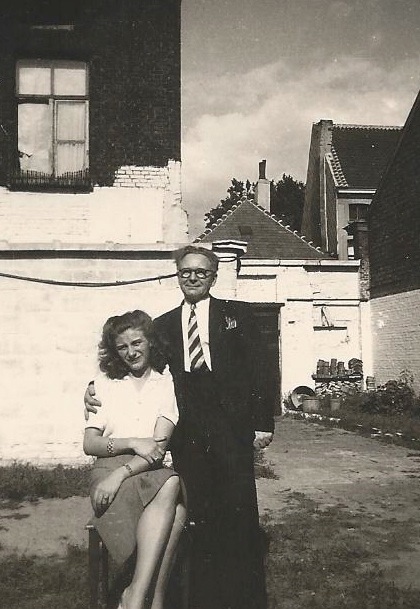

(early photo with her husband)

(early photo with her husband)

Gorr started studying with a well-known Ghent teacher Ms. Polfliet. Contrary to some stories she never studied at one of the conservatories in the country. Polfliet soon recognized the talent of her pupil and proceeded very carefully for quite a time. Gorr was not allowed to sing higher than a middle F. She had to sing scales a lot and slowly her real voice came out: a rich and at the time a rather dark mezzo soprano. Thanks to her uncle Robert Geirnaert she and her sister Suzon sometimes visited the Ghent opera. Due to German support production values and musical performances were quite high during the war (remember Callas’ praise for the German administrators of the Athens Opera). The budding mezzo consulted with a famous Brussels teacher as well: Jeanne Pacquot-D’Assy (two Zonophones) and better known as the wife of bass Pierre D’Assy. Pacquot had been a dramatic soprano who often sang mezzo roles as well and it is possible she put some ideas in Gorr’s head on the possible combination of soprano/mezzo roles which would have grave consequences. Liberation came in September 44 but the first months in the after war period were a period of greater deprivation. Gorr met a young Canadian soldier and for a time dreamed of leaving the country. Nothing came of it and she agreed to set up shop with Félicien Lecompte. By 1946 communications and food situations became less stringent. Young Marguerite Geirnaert was told a famous Walloon pre-war singing competition would restart and she travelled to the small but rich (at the time) textile city of Verviers (to the north east of Liège, the biggest Walloon city). Verviers (60.000 inhabitants) still had its own opera house; well documented in “Cent ans d’Art Lyrique à Verviers” by Georges Cardol. Every biography of Gorr mentions her triumph when she won first prize but Cardol publishes the correct information. The winner was Gilbert Dubuc, a fine Walloon baritone much admired in Flanders (he sang an exceptionally fine Dutch), Wallonia and Germany. Marguerite Geirnaert received one of the five Prix d’Honneur; not bad for an inexperienced twenty-years old singer. The competition and the theatre still exist though there is no longer an opera season at Verviers and the contenders nowadays are not of the quality of yore (Prix d’honneur in 1948: Leonie Rysanek; Honorary mention in 1950: Walter Berry; Winners: Nicolae Herlea – 1957, Luisa Bosabalian – 1961, Tamara Sinjavskaya – 1969- and Renee Fleming – 1985). No real engagement came of Mrs. Geirnaert’s success and she continued to study, this time with another famous Ghent teacher Yvonne Derieck. These remained lean years for the singer and to earn a little money she competed in popular contests where every budding singer could try to earn a few franks in whatever genre. Lecompte lost a lot of money in the after war money reform which wiped away most of richness earned during the occupation (by selling perfume for example to the Germans) and by that time he probably had to pay up for his wife and children as well. In 1949 Marguerite Geirnaert (as she was still known) got third prize in a singing contest in Ostend (official Dutch name = Oostende). At the time it seems she also got some radio engagements at Flemish Public Radio. Did someone important hear her in Ostend or did she audition ? Anyway, she got a three year contract for the opera of Strasbourg as “membre de la troupe” starting with the season 1949 – 1950. She and Félicien were preparing to move to Strasbourg when she received the visit of a Ghent representative of the Koninklijke Vlaamse Opera in Antwerp (official Dutch name = Antwerpen). Their Fricka for performances in De Walkure (in Dutch as was the custom at the time) had become ill and maybe young Geirnaert could substitute in a week’s time. Gorr counted the number of lines she had to sing and decided to accept. Thus she made her official operatic début in Antwerp in May 1949; the only time she would sing an operatic role in her own mother tongue. In Antwerp they were not foolish and recognized her talent but she declined an offer as she had already signed her French contract.

(Rita's sister Suzanne Geirnaert who was a singing artist herself under the name of Suzy Wall)

(Rita's sister Suzanne Geirnaert who was a singing artist herself under the name of Suzy Wall)

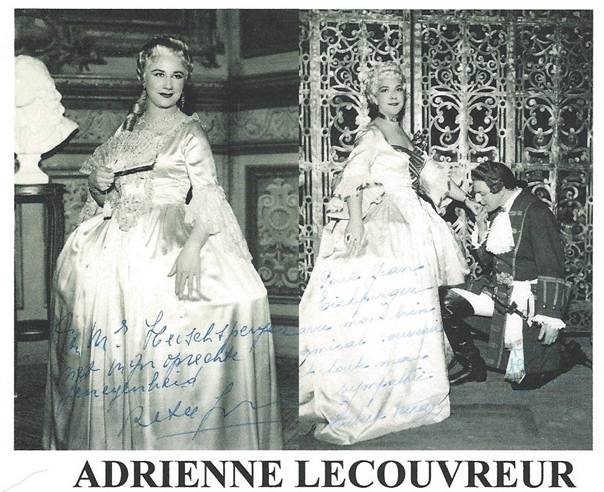

So she started her career in the capital of (what is wrongly known in English) as Alsace, though its real name is Elsass. The German speaking region was one of the victims too of Louis XIV’s aggression who annexed it. After the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 Alsace was once again incorporated into the new German empire and a lot of French adherents left the country (the Dreyfus family among them). Still there remained a strong core of French supporters and French speakers (some 35 % of the population; mostly better off bourgeoisie). At the 1918 armistice Alsace had to be handed over to France again; without a vote as the victors realized the results were not sure to be favourable. This time a lot of German people were thrown out, among them the Tiana Lemnitz family and the soprano would become an ardent Hitler supporter. In 1940 Alsace once more changed hands and government. All young males were recruited into the German army and thousands among them died involuntary as by that time a lot of them preferred to remain French so they didn’t have to fight. Other were rather enthusiastic Nazi’s and it was an Alsace SS regiment that destroyed the village of Oradour (now in its entirety an open air museum) and murdered the whole population. So Alsace once more and this time for definitive became French in 1944 though the common language of a lot of people and above all its mentality remain strongly German. When Gorr and Lecompte left for Strasbourg he advised her to change her too Dutch sounding name into something more suited for her new career like Fernand Smeets (aka Fernand Faniard), Clara Impens (aka Clara Clairbert) or Emma Luwaert (Emma Luart) had done when moving to France. He concocted the simple but easy artist name of Rita Gorr. The couple was so poor they had to borrow the money with her sister for travel expenses. Still the mezzo-soprano’s memories of her three years at Strasbourg were extremely favourable. She learned her trade as a singer and an actor in that place; including all the necessary tricks to survive on the scene. But there was more to the place. “French inventiveness and German discipline” she called it. Musical and scenic preparation were state of the art. Sloppiness was not tolerated and young singers got a lot of help. As so many youngsters Gorr was not one to pace her performances. In fact she would always be famous for not pacing. In Antwerp people had praised her for her vocal talent but added that if she continued that way her voice would just last one year. She profited from the help of soprano Germaine Hoerner who advised her on streamlining her vocal exuberance. Gorr started her career with a mixture of small and not so small roles: Mercedes in Carmen belonging to the first category and Suzuki to the second one; a role she would never sing again. During the next season 1950 -1951 there were roles like Maddalena in Rigoletto and some parts for which she would become famous like Orphée and Dalila. A pity there exist no live recordings of youthful Gorr in interesting parts like Carmen or Venus in Tannhäuser. Her last season at Strasbourg was 1951-1952. As she was allowed some performances on a free lance base she could make her début in the opera house in her home town.

She opened the Ghent season as Hérodias in Hérodiade. Though she was quite successful she did not return to Ghent for another four years. General manager of the house was soprano Vina Bovy, -another Ghent native- who combined management and singing in her own theatre. Probably the elder manager/soprano did not like overmuch competition by another world class Ghent lady which would make Gorr the new favourite. During her last Alsace season Gorr felt her progress was such her career could take a higher flight. She employed a method common today but less used 60 years ago: once more participating in a vocal competition. Gorr chose the at the time well known Lausanne competition where 144 singers tried to win some laurels. This time Gorr won. As a result she was officially received at the Ghent city hall, accompanied by her teacher Yvonne Derieck and her “impresario” as Félicien Lecompte was discreetly called. A more important result was an audition for the boss of the two Paris opera houses Opéra Garnier and Opéra-Comique without telling anyone at Strasbourg. He offered her a three year contract as “membre de la troupe” with the possibility of free lancing during part of the season. She gladly accepted and then told the Strasbourg management that she would not return any more. Her Alsace boss was angry and felt deceived but had to accept Gorr’s decision.

The season 1952 – 1953 saw Rita Gorr in Paris. It was a shock and a disillusion. For a girl of the Ghent working class Paris had a magic reputation as the centre of richness, frivolity and culture besides being the capital of the most important world language (as a lot of people, born during pre-war years wrongly thought). At the Paris opera houses Gorr soon discovered another reality which contrasted with her Strasbourg experiences. She naively had thought Paris meant world class and discovered that performances were often run of the mill, productions were old and worn, musical preparation was often sloppy while work ethics were low resulting in strikes for almost no reason at all. The members of the orchestra for instance wrote themselves an unofficial sickness roster for the months of January and February. Afterwards most “ill” players returned nicely bronzed as they went on a skiing holiday. And then there was the disillusion of the roles offered: often parts like “Magdelaine” in “Les Maîtres-Chanteurs de Nuremberg”; Bellone in Les Indes Galantes; Albine in Thaïs; once more “Madeleine” in Rigoletto besides a lot of other small bit parts. She ought to have known better. Did she really think for a moment that talented older colleagues like Suzanne Juyol, Solange Michel, Hélène Bouvier and Denise Scharley would step out of their way and offer her a free ride ? These ladies did not have the world class potential of Gorr but their many recordings prove that nevertheless they had lots of voice to offer. Another reason for some discontent was the fact the couple Lecompte-Gorr had to move to Paris and Lecompte didn’t like the city; too busy, too much noise, too crowded. Big parts only came slowly Gorr’s way and in the meantime she made her début at De Munt in Brussels; then still a city theatre managed by a concessionary. She quickly became popular in the capital of her own country where her outstanding gifts were soon recognized.

She sang another series of Carmen and some of her best roles like Charlotte, Orphée and Dalila. Her renown led to engagements in Wallonia as well and she made her début in Liège and Verviers. In Paris she would from time to time get some meaty parts like Amneris and Dalila as well but even in her third and last season 1954 – 1955 she had to perform such parts as Puck in “Obéron”, “une voix” in “Prince Igor” and “femme de Théogène” in Nuance de Barraud. From autumn 1955 onwards she felt sure enough to become a free lance singer. Nevertheless she remained at heart a Ghent working class girl still somewhat in awe of “La Grande Nation” and therefore centring her career on France with a lot of engagements in her own country. This is understandable as France and its overseas departments (Algeria, part of France at the time) still offered an awful amount of performances in a plethora of theatres as every town of 100.000 inhabitants (or even less) staged a season of opera and (more popular) operetta. Everything was still sung in the vernacular and French or French speaking artists were numerous. Most of them rarely crossed the borders and did not feel the need to learn their roles in the original languages as there were performances enough in France, Wallonia and the French speaking part of Switzerland. Those were the last years of “l’école du chant français” and one is struck by the richness of talent: Vanzo, Poncet, Botiaux, Mallabrera, Chauvet, Lance (Australian), Laroze among the tenors; Jaumillot, Sarroca, Micheau, Crespin, LeBris, Angelici, Guiot, Monmart among the sopranos; Massard, Borthayre, Dens, Blanc, Bianco among the baritones. Apart from those mezzo’s already mentioned Gorr was joined by Rhodes, Berbié and Kahn as well. Maybe her Flemish and provincial outlook restrained Gorr from going for a real international career though she performed a few times as Dalila with a real world star as Mario Del Monaco (Marseille 1956). Then it was back to Paris for a few guest performances as Fricka in “La Walkyrie” de “Richaar Wakneir”.

(with Del Monaco in France)

(with Del Monaco in France)

The world at large got an idea of this exceptional voice at the end of 1957 when the first complete recording of Le Roi d’Ys appeared with her stunning singing of Margared. The set didn’t sell in the thousands abroad but critics and some managements took notice that here was a singer who sounded like a throwback to the golden age of French singing around the start of the 20th century. Slowly it dawned upon Gorr that there was an operatic world outside France where she could have a place. She started to look at libretti in their original language; especially to Wagner as she spoke herself a Germanic language. The odium clinging to German slowly disappeared and more and more international casts were performing Wagner’s opera’s in that language; even in Italy and France. Gorr sang roles as Venus (with Beirer in Paris), Ortrud (with Windgassen in Strasbourg) and Fricka (with Hotter and Varnay in Brussels): outstanding Wagner singers who undoubtedly confirmed her artistry in Bayreuth By that time it is possible the Wagner-brothers already knew her name. From 1955 on one of their conductors was André Cluytens, another Fleming, born and educated in Antwerp at the Koninklijk Vlaams Conservatorium. The Wagner-brothers thus gave Gorr her real first chance on the operatic world scene because Bayreuth had a far more exultant rank in the fifties than is nowadays a reality. Wieland Wagner (an ardent Nazi, more than even mother Winifred and brother Wolfgang, and a coward who let his mother take all blame) succeeded in making a virtue out of poverty. Even before the war Heinz Tietjen had already used some spare sets and stylized movements (approved by financial backer Adolf Hitler) but now Wieland out of necessity reduced all sets to utter simplicity and acting to a small number of limited gestures. Wieland converted to the political left and immediately his sins were forgiven and forgotten and from everywhere praise was heaped upon his “revolutionary” ideas. Musical and even political press flocked to Bayreuth and stumbled over each other in praising the “denazification” of Wagner and the rebirth of German art (in reality the number of Wagner performances heavily declined during the Nazi area as Verdi became the most performed composer). The Wagner brothers were still lucky enough to have real Wagner voices at their disposal (with the exception of the tenor department) and singers still thought it an honour to sing at the festival for little money and long rehearsal weeks. Critics too in those days had some musical education, still listened to singers and had more to tell than “ X sang well” or “Y was not suited to the role” instead of devoting 95 % of their review to the brilliant concept from an inflated producer’s ego as is nowadays “de rigueur”. Thus contrary to today singing at Bayreuth was noted and an investment in one’s career. Gorr gladly accepted the Wagner proposals and in 1958 sang Fricka in Das Rheingold and Die Walküre and had no problem in singing Third Norn as well in Götterdämmerung. More and more her name circulated in operatic circles and at the end of the year she was asked to participate in one of those mammoth projects: “The History of Music in Sound”; a series of LP’s and books produced by EMI. She recorded arias from Les Troyens and from the original French version of La Vestale (a soprano role, ouch !). Later on EMI would publish her contribution on an E.P. 45 T. My version has the full text of the arias and a musical analysis on the back cover and not one word on Gorr. Gorr was asked as well to record the role of Marthe Schwertlein in the Faust stereo rerecording with De los Angeles, Gedda and Christoff.

(curtain call with Tebaldi at the Paris Aida)

(curtain call with Tebaldi at the Paris Aida)

Her real international career started in 1959 when she no longer limited her performances to France and her own country. She learned Gluck’s Orfeo in Italian for her début at the San Carlo in Lissabon. Opera Magazine published the following review: “Rita Gorr as Orphée sang this serenely beautiful music with genuine feeling and conviction. Her expressive movements seemed so masculine and to stem so naturally from within that only an abruptive feminine head movement there and there broke the spell of complete conviction.” May 1959 finally saw her Italian début as Brangäne in Rome (with Nilsson and Windgassen). And then came the call that often changes a career for the better. Regina Resnik was indisposed and couldn’t sing an Amneris at Covent Garden (a less important theatre at the time but London was the capital of the recording industry). By that time Gorr had already looked at the Italian lines as she had to sing an original language performance later on the same year. She accepted a London début (with Leontyne Price and very much underrated tenor Flaviano Labo). Even a difficult, chauvinistic and nitpicking reviewer as H.D. Rosenthal was bowdlerized and wrote: “ We had Miss Rita Gorr, the Belgian-born mezzo-soprano from the Paris Opéra (a house she had already left four years JN) whose performance was little short of magnificent. Miss Gorr possesses a most beautiful, full mezzo voice, even throughout its register, and used with the utmost musicality and intelligence. This is surely the kind of French mezzo one used to read about. The audience was in no doubts about her abilities and rewarded her with a tremendous ovation. “ It is no coincidence that another hair-splitter, Dutch critic Leo Riemens, used almost the same words in September when she opened the Ghent season with an original French (the tenor sang in Italian) La Favorite performance: “ Being born in Ghent, Rita Gorr makes a few annual appearances here, and these are the rare occasions when she can be heard in her own country. She is now at her very peak. The voice has lost some of its dark velvet tone of a few years ago, but has gained in dramatic intensity and acquired some luminous top notes. I cannot imagine a better Leonora, especially in the French version, where Donizetti approaches the grandiose style of Meyerbeer. Again and again I was reminded of such legendary French contraltos as Marie Delna and Jeanne Gerville-Réache. In these lean days when France does not seem able to produce any large voices for the dramatic works of the first part of the last century, Rita Gorr is one of the few artists who evokes that glorious period.”

(with Tebaldi and Uzunow)

(with Tebaldi and Uzunow)

Nevertheless Gorr had not forgotten her humble Flemish origins and she still felt a bit unsure when singing with a real legendary diva. Félicien Lecompte had to convince her she was worthy of the occasion as she feared to be not on a par with the star. One must have lived throughout the fifties to know the impact of the name of Renata Tebaldi. At the time the Italian soprano’s name was as well known as Callas’. Their rivalry was commented upon in popular magazines and discussed by a lot of people and real singing was often heard on radio before or after a programme with pop singers. 50 years later Tebaldi’s name still rings out loudly but only among adapts of operatic singing while Callas is still the symbol of bel canto ( and a lot of pop lovers wonder if operatic singing means wobbling and shrieking above the staff ). Callas had visited Paris in 1958 and a grand occasion it was: the last public appearance of president René Coty before handing over power to Charles de Gaulle. The Callas concert was (happily for us) broadcasted in Eurovision and as at that time most Western European countries had only one (public) station all Europe watched it. Tebaldi demanded the same red carpet treatment for Aida and got it. Radio listeners got the whole performance while on TV we got the third act (like we got the second act of Tosca one year earlier for Callas). The Paris opera could hire a few local stars to shine humbly besides Madame Tebaldi and asked Rita Gorr as Amneris. Tebaldi’s tenor Dimiter Uzunov did not raise to the occasion but the performance became legendary for Tebaldi’s crack on the difficult high C in “Qui Radames verra”. People in the house or glued to their radio set were far less impressed by Tebaldi than by Gorr’s magnificent Amneris and it remains a pity that we don’t have a single video recording of Gorr at her best and have to do with the few phrases in Aida’s third act. A few weeks later Gorr once more went into the recording studio; this time for her first vocal recital. At the end of the fifties or the beginning of the sixties a recital still meant an artist had already proven him or herself to be a force to be reckoned with and there was not the plethora of recordings typical for the seventies, eighties and the advent of CD. Only the real great would have an album with a big label. That EMI-recording is indeed a sensational one. There is the rich and personal colour of the voice. There is the phrasing which deserves the epitaph noble and shows Gorr to possess a perfect legato and on top of all are the splendid high notes:. “Eine Bombenhöhe” wrote the German reviewers. One has to be careful with recordings but one hears too the impressive volume, often called “the house rattling amplitude of Rita Gorr” by the British press. With historical hindsight it is easy to point to a little shrillness here and there (the top notes of “Divinités du Styx”) but this is because we are aware of the vocal tragedy that was to come 6 years later. Now we know it was no coincidence three of the twelve recorded arias were written for soprano but at the time this was mentioned somewhat in passing as Santuzza was often sung by mezzo’s with a good top; Alceste could be sung by a mezzo but Isolde’s Liebestod –impressive as it sounds- shows the tessitura lies a little too high for the singer. If one takes a look at Gorr’s chronology for a moment one has the impression she was slowly turning to the German repertoire. Once more she was a guest at Bayreuth where she performed Ortrud in one of the best sung Lohengrins ever: with Sandor Konya, Elisabeth Grümmer and -a colleague of long standing- French baritone Ernest Blanc as Telramund. Of course several great Italian or French mezzos have sung Lohengrin but I doubt they sang Mahler-liedercycles as well: Kindertotenlieder in 1959 and Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen in 1960 (two radio recordings once available on LP). And then there was Gorr’s debut at La Scala in 1959 with Kundry (in German and a soprano role); received with a lot of enthusiasm. Gorr herself always claimed, and there is little reason not to believe her, this role came as compensation for her initial engagements. La Scala had asked her for a series of Amneris and Didone (in Italian with Mario Del Monaco). When she heard of it Giulietta Simionato was livid and demanded that “her” roles would not be given to the Flemish mezzo. Simionato was already grumbling on the ascent of young Fiorenza Cossotto and she vetoed the coming of another formidable and even more experienced mezzo who had a few extra decibels to spare. La Scala gave in to Simionato’s demands and thus it was to be Kundry with co-Fleming André Cluytens in the pit and Sandor Konya as Parsifal for Gorr’s début. (She would repeat the role at La Scala in 1961) In Edinburgh she sang some performances of Iphigénie en Tauride (once more a soprano role). For RCA she recorded her by now famous Fricka in the best sung Die Walküre ever (Nilsson, Vickers, London, Brouwenstein). In 1962 she performed once more her (soprano) Iphigénie in Firenze plus several (soprano) Medée’s in Paris. In September 1962 she recorded her Dalila for EMI with beefy Jon Vickers. I remember Franco Corelli saying on Walloon radio he was studying the role and would record it and thus his Samson was one of the many recording projects he cancelled. One month later Gorr definitely knew she was a star herself when she made her début at the Metropolitan. She came in at 1.000 $ a performance and one season later her fee would rise to 1500 $; the highest fee for any mezzo on the roster with the exception of Simionato who was paid the same amount as the star sopranos. At the time Gorr’s fee meant two and a half years of salary of a schooled clerk or blue collar worker in Flanders. Gorr’s début was a triumph. The voice rang out freely and oldtimers still agree that some of her performances as Amneris and Santuzza are among their greatest souvenirs of that New Golden Age of Singing. Her fifth performance was broadcasted and is one of the greatest live performances of Aida on record. In his “Sign Off for the Old Met” Paul Jackson devotes several pages to the conductor and singers (Solti, Price and Bergonzi) and he is full of praise for the mezzo. He can only regret as we do that this is the only one of her 44 Met performances which was broadcasted. In detail he describes her dignity in phrasing and acting, her glorious high B flat during the judgment scene and her easy mastery of the murderous tessitura crowning the scene with a stunning A. He thinks Gorr to be a brass band on her own and then there is one small sentence a bit less flattering: “ she skirts the upper side of the pitch occasionally.” Probably few people noticed it in October 1962 while we now know that it is a sign of one of the great vocal collapses. After her successful performances Gorr proudly sent dedicated (in Dutch of course) Met photographs to her parents and sister. It was a bit ironic that afterwards Gorr fulfilled other engagements elsewhere while her roles at the Met were sung by her intimate friend….Giulietta Simionato.

Next year Gorr mostly sang a heavy dose of mezzo roles (Eboli in London and New York), Amneris (New York), Ortrud (London). Still some soprano roles popped up like Anita in a New York concert performance of La Navarraise and one wonders why she absolutely wanted to sing “Dich teure Halle” and part of Sieglinde’s role at Het Festival van Vlaanderen in her own Ghent. 1964 was probably Gorr’s last carefree year. Her agenda shows some performances in Paris and bigger French provincial theatres, the Met in New York and a last return to La Scala as Brangäne (once more with Nilsson and Windgassen). She finally recorded her magnificent Charlotte with Albert Lance for a new company, founded by other singers and in July she sang her second recital for EMI: Italian arias (no soprano arias). By now we were accustomed to a small shrillness though apparently nothing to worry about. People who heard her Amneris at Ghent that year told me it was pandemonium; the house coming down after the judgment scene. By that time Gorr knew her worth and was not slow to show it. At the dress rehearsal of Samson et Dalila in Dallas (the declining) Mario Del Monaco turned up in a just bought cowboy costume and Gorr refused to continue if he didn’t behave and took the rehearsal seriously. Eight years earlier she would definitely have shut up when performing with the star tenor in Lyon. And then there was the vocal tragedy of 1965. Steep as Gorr’s rise was from 1959 on, steeper was to be her fall.

Jan Neckers