(early photo at the lake of Annecy)

The Rise and Fall of RITA GORR, part two

(all photos courtesy and copyright Freddy Verschaffel and Suzanne Geirnaert)

(early photo at the lake of Annecy)

(with her friend and fan Freddy Verschaffel from Ghent)

During the first 7 months of 1965 Gorr is busy in Europe: Werther in Paris (with Turp), Samson at the Liceu (with Fernandi and Flemish tenor Jan Verbeeck; It is claimed that for a time she had a crush on him but he preferred a Walloon dancer), Aida in Strassbourg, Tannhäuser in Paris (with Beirer). In August she leaves for the States where she sings a single performance of Ortrud at Tanglewood. It is an excellent preparation for the recording that takes place from the 23th till the 28th of August at Symphony Hall in Boston. Her co-stars are Sandor Konya, Leontyne Price and William Dooley. Price doesn’t show up or has not learned her part and at the sessions it is all-purpose Lucine Amara who has to save the recording. It is still not clear what happened at the recording but Gorr’s voice is in bad shape. The top is in shreds and she makes some painful sounds. In his booklet notes with the original recording producer George Marek explains that such a 4LP-effort doesn’t come for free. RCA is used to recording in Rome where the chorus and orchestra of the Rome Opera house (often hidden as Coro e Orchestra RCA Italiana) serves the company well and cheaper as at the time the salaries in the US are far higher. Marek therefore takes quite a risk in working with the Boston orchestra and six days recording time is rather short for a long opera, which in the recent true RCA-style is recorded without cuts; even adding a long solo for Konya cut by Wagner himself. Marek and conductor Leinsdorf (and everybody else at the sessions) must have heard Gorr’s problems but still include some shrieks and false notes in their final edition. Maybe they thought the mezzo suffered from a cold; maybe they already knew she was in vocal difficulties but even then one wonders why they didn’t try some recording wizardry later on or asked her to rerecord some notes at a moment she was in somewhat better shape. The voice has recuperated somewhat in October as proven by a live tape of Werther when Gorr returns to the Koninklijke Vlaamse Opera in Antwerp where she made her début. In the late fall she returns to the Met in its last season in the old house. By then it is clear the voice is still in difficulties and she cannot simply claim a cold that racked the Lohengrin sessions. “The sound is dull and uninflected” states a review on Samson et Dalilah. Irving Kolodin is even more severe when he writes on an Aida with Franco Corelli: “Rita Gorr’s explosive lurches for dramatic effect as Amneris.”

(as Amneris and Santuzza)

(as Amneris and Santuzza)

General Manager Rudolf Bing cannot miss hearing Gorr’s problems but is probably not much over worried as that same season Grace Bumbry makes her début: a fine looking woman with a rich mezzo and a brilliant top and moreover a black American which appeals to the liberal New Yorkers during the days of civil rights action. From the old Met Gorr goes to France with Brangäne in Paris and Charlotte in Marseille. In spring she sings a series of fine Ulricas at London’s Covent Garden. No problem as the tessitura is less exposed than other mezzo parts. In June 1966 she returns to London for a killer role: Eboli. This time the critics are less enthusiastic. Opera Magazine notes that “O don fatale exposed fatal strains in the higher notes.” By this time Rudolf Bing definitely knows there is something wrong that cannot be repaired. For the opening season at the new Met in Lincoln Centre he originally thinks of Gorr as Laura in La Gioconda; one of the opening productions for which every singer is elbowing with all force at his or her disposal (witness Bergonzi’s rage when Corelli gets the role of Enzo). The plum however goes to Biserka Cvejic. Gorr only gets 4 performances of Amneris and on the 2nd of December 1966 her Met career ends. With Bumbry, Cernei, Cvejic, Dalis, Ludwig, Dunn etc. Bing has ample choice and he has started negotiations with Italy’s new star Fiorenza Cossotto who will arrive next season. At the same moment of those last Aida’s the recording of Lohengrin appears on the American market. Most critics are still polite but they all write that Rita Gorr sings flat and more or less yells her high notes. I can scarcely believe my ears when the recording appears in Europe and due to the record library in my hometown I hear the results. This is uncorrected shrieking and age has not made me and most listeners more mellow. Comments on the world wide web now go from “yelling” to the damaging “a party record.” Lohengrin means the end of Gorr’s recording career as well. Communication may not have the lightning speed of today but it definitely is not slow. Moreover, as contracts in those days are negotiated only a few months in advance opera houses can easily decide on short term not to engage a singer in distress.

(early photo studying a vocal score)

(early photo studying a vocal score)

The results are immediately to be noticed in Gorr’s agenda. In 1967 her theatres are no longer the Met and La Scala but Bordeaux, Arles, Rouen, Limoges. Her partners are not Franco Corelli, Richard Tucker or Leontyne Price but Géri Brunin, Tony Poncet, Jean Brazzi, Adrien Legros. In May 1967 she concertizes at the Ghent Opera with Giuseppe Di Stefano, Berit Lindholm and Renato Capecchi. That’s when I first assist at a Gorr performance and I am duly impressed. The voice sounds so rich, the legato is perfect, the phrasing is noble and the volume when she opens up is overwhelming; especially in a small theatre. This is indeed “the house rattling-amplituted of Rita Gorr” as English critics write. And then there are the top notes: big and flat at the same time (as proven by the well known pirate recording). With hindsight I wonder why she makes some strange choices indeed. By that time she must have known that she no longer easily manages the two octave compass of “O don fatale”. At a concert she could easily have sung a less taxing aria. Or, and well possible, she wouldn’t allow herself to think the voice didn’t respond anymore as it did some years before. When she sings “Ai nostri monti” with Di Stefano she is at her most impressive as no shrieks are necessary.

(after the 1967 gala with Vina Bovy signing on her back, on the right of Gorr her teacher Mme Vanderrieck)

(after the 1967 gala with Vina Bovy signing on her back, on the right of Gorr her teacher Mme Vanderrieck)

(ditto, Gorr hugging radio producer Etienne Vanneste, on the right from Vanneste the young Gerard Mortier, next to Mortier Berit Lindholm . Fourth person from the left Renato Capecchi holding a cigarette)

(ditto, Gorr hugging radio producer Etienne Vanneste, on the right from Vanneste the young Gerard Mortier, next to Mortier Berit Lindholm . Fourth person from the left Renato Capecchi holding a cigarette)

Her career slowly peters down. At the end of the sixties, the start of the seventies she most of the time performs in her own country or France. From time to time she appears with success at Covent Garden, the only major house that still engages her though always for rather low lying roles like Ulrica. No recording firm offers her a principal role after the Lohengrin disaster and thus we shall never hear her Adalgisa in Norma; a role she could not perform in the Callas-Corelli recording due to theatre contracts (Ludwig was her not very authentic substitute). In these declining years it is not as if the voice is completely in ruins. There are some off-days but there are still glorious moments as well. I especially remember a Principessa di Bouillon at Ghent in 1972. That day she is once again in complete control of her instrument and the impression is overwhelming. Her “Acerba volutta” has the house on its feet and the duo with Adriana is simply marvellous. Her voice especially blends well with the impressive spinto of Jacqueline van Quaille – at her best so much like Gina Cigna and a voice that should have had a far more impressive career. It is one the greatest moments I ever witnessed in an opera theatre. But a few months later Gorr once more essays ‘O don fatale” in an Antwerp concert for the Lions Club and the listener shrinks when he hears some of her sounds.

(early photo, sister Suzon, Gorr, husband and unknown)

That same year after an absence of twenty-three years she returns to Flanders and starts to live at the villa Casa Lyra in Deurle, an expensive village not far from her Ghent. Her husband who never felt at ease in busy Paris much prefers the Flemish rural surroundings. According to Gorr’s French biographer she told him her husband by that time so resents her career he often hides letters and contract proposals whith the result her career goes downhill. It is possible this happened once or twice but this is not the main reason for a rather painful finish as a prima mezzo. The whole operatic world knows that the voice is not at all reliable any more and declines to engage her. In 1973 an Amneris at a theatre she almost owns, the Ghent Opera, is a disaster. As a result Bart Lottigiers, new manager of the house and nowadays better known for being the grandfather of Flemish semi-“superstar” Helmut Lotti, refuses to engage her anymore. Her Ghent fans are very angry as some of them prefer to remain deaf to some of Gorr’s wilder sounds. Husband Félicien Lecompte’s mental health has been declining for years and he dies in 1976.

(with her husband)

(with her husband)

By that time it is almost sure Gorr has already met the “bull dog” as some people call her later friend and partner Jocelyne Hourriez. The Walloon lady has asked Gorr’s advice on the correct tessitura of her son and “les deux femmes se prennent de sympathie” as her biographer elegantly phrases their relationship. He tells us that it is Hourriez who stimulates Gorr to continue her career and even to accept lesser roles. It is a fact that Hourriez jealously guards every action of Gorr’s life and career from that moment on. Is theirs a relationship based on more than friendship ? Gorr alwas denies it to her family but we may not forget that a lesbian relation in Gorr’s youth is simply unthinkable. Other sources (in the gay community) confirm that to them Gorr admits a full relation with Hourriez. The years between 1975 and 1980 are a period of indecision.

(with her secretary)

(with her secretary)

Gorr does not like to be demoted and at De Munt she gladly accepts low lying roles like Orphéee and Fricka. But she sings too the role of countess in Pikova Dama. Deep in her heart she remains a singer of principal roles. In 1980 I lecture on tenor Carlo Bergonzi -who sings a recital at the Ghent Opera- for the local Vrienden van de Lyrische Kunst (still going strong after 56 years of activity). Gorr is the most prominent honorary member of the organisation and she writes a bitter resignation note. The Vrienden have always devoted their activities to lectures on operatic works and have never devoted an evening to a single singer. She has no problem with this new policy but is very angry that her career is not the first to be lectured on. Gorr has not even the grace or politeness to write her note in Dutch but prefers French as if Ghent is still socially terrorized by French speakers like happened in her youth. Still this is the year she definitely switches to comprimaria, probably influenced by Hourriez as the ladies have a reputation of being not very generous with money. There is an ugly story by several witnesses that Gorr refuses to pay her part for the care of her mentally declining mother.

(with her sister and her parents)

(with her sister and her parents)

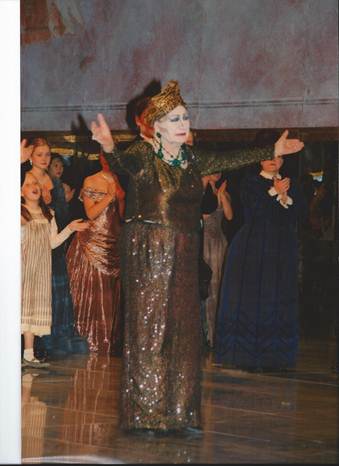

For years Gorr makes a nice second career in France and Wallonia in several roles: countess in Pikova Dama, Madame du Croissy in Dialogue des Carmélites (in Germany and the US as well) and especially the mother in Louise where she still displays some voluminous and impressive notes. Even for the small bit parts there is a lot of jealousy. The defunct Opéra International (nowadays Opéra Magazine) publishes a bitter and jealous letter of Gorr when she gets the message that another former world star has succeeded in snapping away some of Gorr’s promised countess performances (Régine Crespin is the culprit). From time to time the prima donna feelings rear its head and on Youtube there is a video of a concert she gives in 1993 in a small church in a still smaller Walloon hamlet (the Editor has to drive for hours to find it and at first does not believe this is the place to be). The voice is no longer able to perform some of the difficult arias she has chosen but there are still impressive remains of a once formidable voice to be heard.

(Stridi la vampa, her bis number, cond. Georges Octors)

Six years later she has nothing left. In 1999 De Vlaamse Opera invites her for a series of performances of Pikova Dama and wants to celebrate the 50th anniversary of her début in Antwerp. She is a guest of honour at the press conference where the season is presented. From the moment she takes her seat it is clear she doesn’t feel at ease. This is no longer her old house where she sang almost for peanuts to make some of her Ghent fans happy. Karel Locufier, the concession owner in those long ago days, often had to take a mortgage on his house to pay everyone. That somewhat shabby opera theatre doesn’t exist any more. The Flemish Government (arts, education, roads etc. are a Flemish and not a federal competence) has generously subsidized the complete restoration of the theatre which has once more regained its 19th century glory. The foyer for instance is almost an exact copy of the famous mirror hall in Versailles and has the same size. Ghent is now part of De Vlaamse Opera which is first an Antwerp based organization. Gorr cannot believe her eyes when she looks at some 150 journalists in front of her (in reality most of them are not journalists at all but people with some ties to the house). And then there is the language of the press conference: correct Dutch as understood from Groningen in the North of the Netherlands to Halle to the south of Brussels. Gone are the days when everybody mixed their local and not very beautiful Ghent dialect with a smattering of bad French that made every true Frenchman smile. The general manager gives all details of Gorr’s celebration and offers her the mike. There is almost a feeling of panic in her eyes and she hesitates. She realizes everybody will laugh if she speaks her Ghent dialect and once more her old working class instinct of the thirties takes over . One doesn’t speak Dutch with one’s superiors. So she haltingly starts saying a few words in French and then looks into the blazing eyes of the journalist in front of her. “Speak Dutch” he clearly hisses. She immediately stops and hands over her mike to the general manager. Granted, maybe this was not my “finest hour” but when one is willing to perform a role in Russian, it cannot be too difficult to clean up one’s own dialect for a few sentences. The producer of the new Pikova Dama is Guy Joosten and it is well done. But Joosten still cannot hide his plain theatre education. He has his choice of Hermann approved by the management and he casts the difficult role of Hermann with a tenor who has performed 226 times at the Metropolitan; mostly as messenger in Aida. As a result John Horton Murray is widely praised for his acting capacity and damned for a voice unsuited to the role. The day of the celebration starts in disaster. The tenor cannot utter a sound and the management starts a series of desperate phone calls. At seven o clock in the evening a substitute arrives; Russian tenor Alexei Stablianenko; a real Hermann. Horton Murray accepts to act the role while the Russian tenor sings from a box to everyone’s joy. The performance sails smoothly on and at the end Gorr gets a nice speech and flowers from the management.

(good-bye in Ghent)

(good-bye in Ghent)

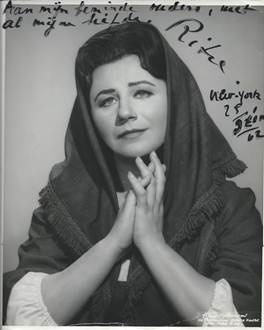

The mezzo is wise enough to refrain from speaking. She still acts well but nothing in the voice reminds one of the great mezzo’s of the age. She continues her comprimaria career and at the end of 2002 she returns to Antwerp as principessa in Suor Angelica. She now realizes her career is over and moreover she has some heart troubles. She speaks more and more of retiring and returning to her beloved Ghent. She definitely ends her career with a last countess in her home town in 2007. For a short time she tries to take up a new life in Ghent but that modern fully re-dutchified city is no longer the town of her youth. Opera is a thing at the fringes of Flemish society and retired operatic singers are no longer celebrities but just plain old people. Madame Hourriez too doesn’t feel at home in Ghent and the couple moves to the small city of Javea (Xabia) at the Costa Dorada in Spain where Gorr has a villa since the seventies. Here madame Hourriez can isolate her better and prevent too much interfering from Gorr’s Flemish family. The villa has the slightly ridiculous name of Sirenma (operatic connoisseurs, this should be an easy guess). Gorr’s last year is not an easy or comfortable one. She has to use a wheelchair and is not properly taken care of in her own home. Indeed, she is completely neglected and lives her final days in a home Casa Bon Repos. She has to be taken to the Ospedale in Denia where the old lady is visited by one of her Ghent fans. He almost doesn’t believe his eyes as he well knows she is not poor at all. She has heart failure and dies on the 21st of January 2012. Madame Hourriez doesn’t think it necessary to inform her family and the sad tidings only turn up next day so that everywhere one gets the wrong date of Gorr’s decease. She wanted to be buried in Ghent but even her last wish is not granted and she has a simple grave in Javea.

(a photo dedicated to her sister + photo of her sister under her artistic name)

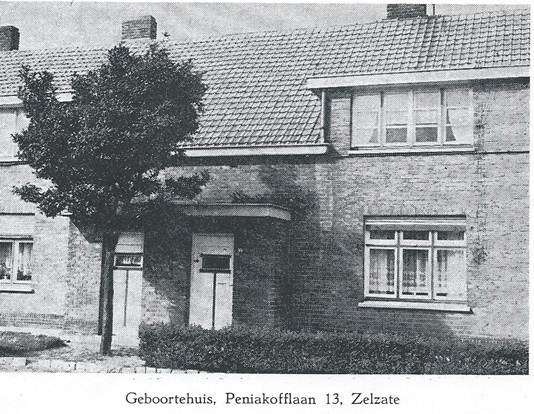

(Gorr's house of birth)

(the first photo of her grave)

(the first photo of her grave)

Jan Neckers