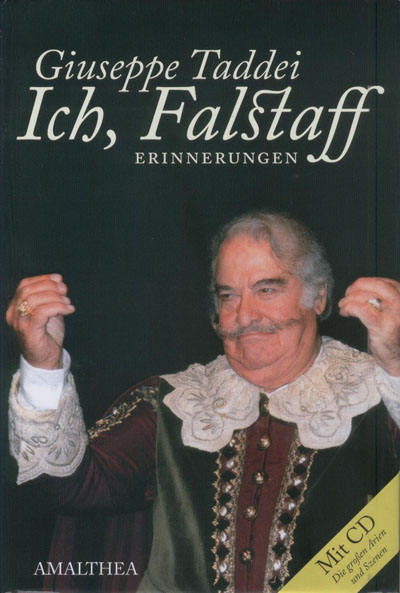

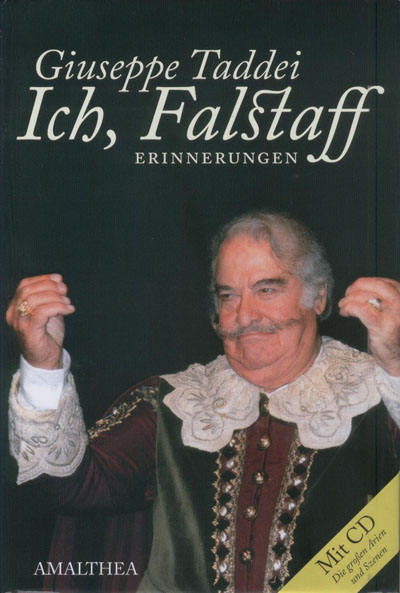

Giuseppe Taddei: Ich, Falstaff Erinnerungen.

Giuseppe Taddei: Ich, Falstaff Erinnerungen.

Amalthea Wien, 336 p., 2006.

www.amalthea.at

What a fine book on a fine singer this could have been.

But the ghostwriter is the singer's son-in-law and the book is a present for the singer's 90 th birthday and why would anyone try to spoil the party?

But a missed chance it is as the many illustrations prove. Taddei is clearly one of these singers who kept every piece of paper ever written about him, who still has a copy of any letter or document concerning his career and so we could have got not only the story of Taddei but of seventy years of singing as well.

Do you know of any other singer still alive who started his career with Iris Adami-Corradetti, Francesco Merli, Alessandro Granda and many others and who ended at the side of tenor Marcello Giordano as an 87-year old Benoit.

Taddei must have been one of the youngest male singers ever to make a début. He was only twenty when he sang Heerrufer in Lohengrin in the Rome Opera where he shared a room with another aspiring young singer, Mario Del Monaco.

He started out with some small roles in that company, tutored by Tullio Serafin but soon there were some plums as well. He was a ripe old 21-year Amonasro and father Germont.

There is only one small sentence that refers to some vocal problems at the top of the voice at the time but roles like Jake Wallace or Silvano tell us that the possibility of a bass-baritone was still looming heavily.

The San Carlo in Naples and the Carlo Felice too heard him. He is rather discreet on the political situation in Italy and the word ‘fascism' is not to be found. He was a soldier in the Italian army but was allowed to remain in Rome and perform on a regular base to the envy of many simple soldiers.

He was part of the Italian company that performed in Berlin in 1941. Incidentally, the photo on page 70 mentions Licia Albanese as one of the performers but here his memory plays him a trick as the soprano was in the US and the lady in the picture is definitely not Albanese.

The turning point for Taddei came in 1943 when Italy got an armistice and the king and his new government dithered for a month before deciding to declare war on Germany.

In the meantime the Germans invaded the whole country and laid their hands on every Italian soldier they could find. Di Stefano fled to Switzerland , Del Monaco escaped too but others like Taddei and Bergonzi went to a prisoner-of-war camp.

Taddei knew how to ingratiate himself with the Germans and soon he became a favourite ‘Lagersänger'; a camp-singer.

He however didn't restrict his activities to his co-prisoners but sang a lot for the German army as well. Not being difficult, he immediately offered his services to the American and Soviet armies after the occupation of Austria.

Then the story becomes a little bit unclear. The singer tells he remained in Vienna for several years where he soon became one of the favourites, greatly admired by Karajan.

One wonders why a promising singer would stay in poor, bombed-out, downtrodden Vienna with all its problems due to the four-powers occupation instead of going home and resuming his career?

Could it be that Taddei was maybe a little bit less apolitical than he pretends? Or was he maybe too much of a favourite of the Germans and did his co-prisoners gave him some warning to stay away till things cooled off?

By 1948 his real great career started. That's where the book doesn't help any more.

We don't get the story of his career but just a number of often very humorous anecdotes and the big sigh that his life consisted of packing and unpacking.

That's where the complete chronology at once frustrates the reader though telling a lot as well.

Son-in-law doesn't give us a logic chronology, day after day but classifies Taddei's performances per country, and in the country per opera house and it's only then the date makes it logic appearance.

Therefore it's almost impossible to follow Taddei's career in its rise and fall and it is even more difficult to find back a thread in the roles he is asked to sing. But on the other hand it clearly shows where he is in and when he gets out.

Take La Scala for example. From 1948 till 1952 he clearly is a big favourite, singing 18 roles and then his career there peters out:

Chénier and Zauberflöte in 55, Elisir in 58, Butterfly in 61 and that's it.

There is a reason of course but Taddei never mentions it by name. The baritone liked his plate of spaghetti extremely well and he became rather chubby.

Moreover his eternal smile and his jokes were well known and clearly showed in his stage behaviour. Therefore La Scala decided he didn't really have ‘le physique du role' and he was supplanted by Ettore Bastianini who looked far better on scene though he was a less cultured singer.

Taddei succeeds in not once mentioning the name of his rival. Gobbi gets a few entrances and even a photo of the two men in Elisir but Bastianini with whom Taddei sang Elisir as well doesn't.

Then there is the short and small American career.

Taddei tells us that Bing requested an audience in a hotel room which Taddei refused, saying he ought to be seen and heard on a theatre scene. And he admits there was a problem with fees.

In reality Bing wanted Taddei very much as here was a baritone who could sing all Italian roles, the Mozart ones included.

But correspondence between Bing and his European representative Roberto Bauer on the début of Carlo Bergonzi reveals us the presence of Lidouino Bonardi, an agent shark of importance. As he was paid on commission he went for the highest fee possible and he got Taddei a lot of financially rewarding engagements as the baritone recognizes.

It is Bonardi's insistence on big money according to Bauer that leads to the non-engagement of Taddei.

To give one example of Bonardi's demands: in 1956 he requested for the completely unknown Bergonzi the same fee Jussi Björling received at the Met. As a result the Met lost Taddei and only got him at a moment when the honour mattered more to him than the money.

At almost 70 he made his belated début as Falstaff, returning three years later as Dulcamara. The Met's and other houses' loss was Vienna's gain as here Taddei made not only his artistic but his real home as well.

The baritone doesn't think it necessary to discuss his voice. So we never get a picture of what he really liked to sing, what suited his voice best, when did the decline start.

It is clear that his vocal longevity was extraordinary. I heard him in 1978 when he was 62 and the sound was unmistakeably Taddei, well rounded, warm and with the necessary decibels.

By that time he had thrown out many of his former roles which were too uncomfortably high-lying as an easy top was never his real forte.

He had become more of a bass-baritone taking from the repertoire those roles which can easily be sung by either baritone or bass: Schicchi, Falstaff, Jake Rance, Scarpia and the Mozart roles of course as he was one of the few Italian singers who really felt at home in Mozart.

He was an extremely good singer of Wagner as well, though in his own language. Other singers who heard him in Holländer, Parsifal and especially Meistersinger said that he completely changed the perception of Wagner as just the composer of overlong and boring monologues.

Taddei was one of the favourites of RAI when Italian radio regularly broadcasted self-produced opera performances, often with stellar casts. This was his and our luck as so many of these performances later on were put on record.

Taddei himself complains he was neglected by the major recording companies but here I fear that Signor Bonardi too played an important role.

Most important Taddei-roles are now available and they reveal a big, very healthy voice, maybe lacking the ultimate in colouring but compensating with style and rolling sound: a voice which we all so much took for granted and which is nowadays sorely missed.

Included with the book is the CD issued by Preiser.

Jan Neckers, Opera Nostalgia