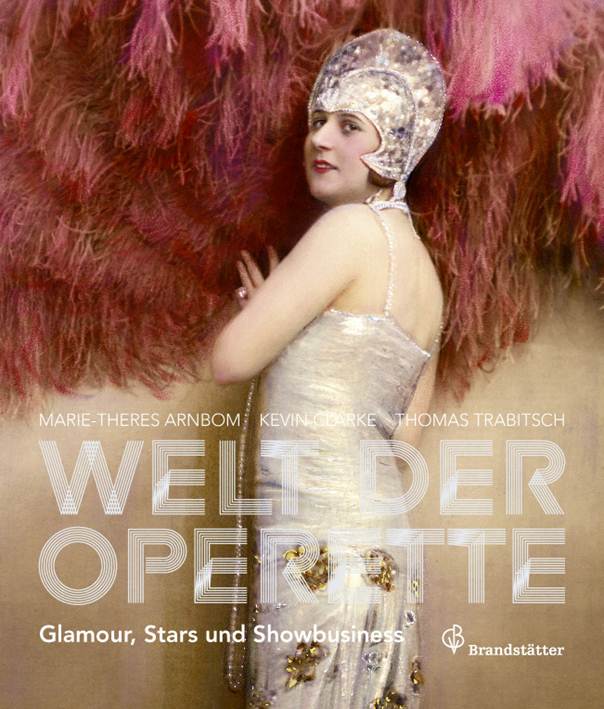

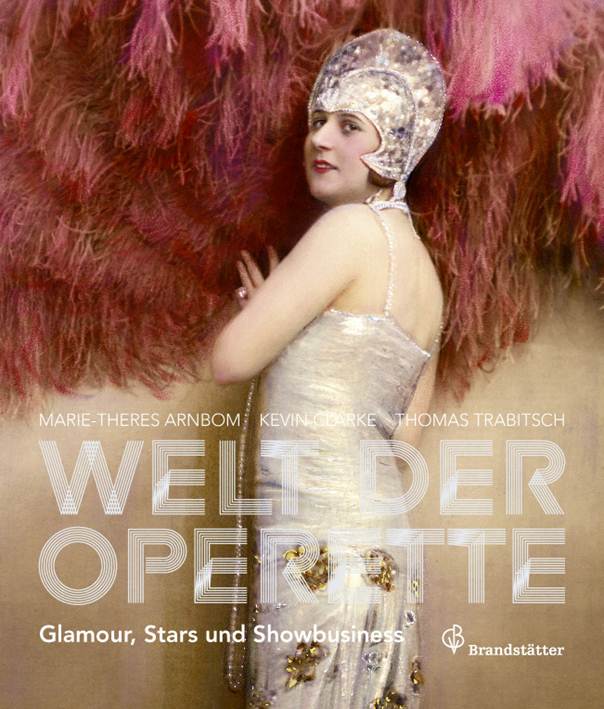

WELT DER OPERETTE

GLAMOUR, STARS UND SHOWBUSINESS

By Marie-Therese Arnbom, Kevin Clarke, Thomas Trabitsch

291 pp, 2011 Brandstaetter Verlag Eur 39,90 Click here to order

This big and lavishly illustrated coffee table book appears as a companion to an exhibition at the Österreichischer Theatermuseum in Vienna. The museum owns the collection of Hubert Marischka-papers. He was a famous operetta tenor and creator of a lot of Imre Kalman’s operettas but he was also the son-in-law (and successor) of Wilhelm Karczag; owner of the most important Vienna operetta music publishing house. Two highly competent operetta historians, Marie Therese Arnborn and Kenneth Clark, are responsible curators for the exhibition and were editors for this book. They are assisted by other excellent authors; the best known among them Kurt Gänzl and especially Stefan Frey, writer of illuminating biographies of operetta greats like Franz Lehar, Imre Kalman and Leo Fall.

Mind you, this book is not a history of operetta, not a German equivalent of Richard Traubner’s important work. You won’t find a complete history of the genre as most of the authors concentrate on the history of operetta in German speaking languages (especially in Vienna) and its influence in other countries. There is a fine article on how and why the Offenbach formula conquered the capital of the Danube monarchy due to the efforts of von Suppé and Strauss jr. Indeed they were so successful that even today Vienna is the symbolic world capital of operetta. One of the authors bitterly remarks that in reality there is only one theatre –the subsidized Volksoper- that regularly though not permanently performs operettas; quite a contrast with the heydays of operetta before World War I when up to five privately run theatres competed with each other. Interesting is Kurt Gänzl’s essay on the ways Viennese operettas caught on in the Anglo-Saxon world, reminding us in an aside that in its turns Sydney Jones’ The Geisha (more successful in Britain than any Gilbert and Sullivan) was an immense hit in the German speaking countries.

/ >

The main part of the book concentrates itself on the rise and fall of the Hubert Marischka-empire; a tale of love, intrigues, opportunities and above all big money to be earned or lost. Operetta lovers like myself will be surprised to learn that the poorer Vienna suburbs got nostalgic old-Vienna operettas most of the time (mostly by the unjustly forgotten Edmund Eysler) while the far more expensive productions in the city centre performed the more international scores, composed by Lehar and Kalman. The fall of Marischka’s empire in 1935 was not only due to a loss of interest by the public though it is true that the far cheaper movie visits were heavy competition (some composers- Robert Stolz prominent among them- composed quite acceptable movie operettas). The main cause however was political. Kevin Clarke draws the attention on “die gute alte Jüdische Operette” as most lyricists, libretto writers and composers were Jewish (Kalman, Jessel, Abraham, Eysler, Korngold, Oscar Straus etc.) The advent of the NSDAP in Germany closed all business opportunities for Karczag’s publishing firm in its biggest market. It is fair to say it already was in stormy weather as Viennese socialist politicians financed cheap housing by levying an impossible 30 % tax on every ticket sold.

In Germany officially purged everything Jewish though the Nazi’s preferred not too dig too deeply into Johan Strauss’ forefathers as they were well aware they would find some “unsavoury” things and they knew well enough how ridiculous their banishment would look. This purge gave chances to new operetta composers, Nico Dostal and Fred Raymond the best among the new crop. Talented they were but the old operetta formula was now too tired to survive much longer (1st act-boy meets girl, 2nd act-boy and girl quarrel-3rd and short act-they reconcile). In 1938 the Nazis easily annexed Austria and they repeated their purifying acts, opening the operetta business to some opportunistic people like Rudolf Kattnig, author of the fine Balkanlieve (which strangely enough was not performed during the war in Vienna). We learn in the war chapter that the Nazis simply got control of all theatres by heavily subsidizing all operetta performances; an offer nobody could resist. The war brought such havoc with it that from 1945 on a lot of the libretti simply sounded so outworldly with the result that “operetta situations” became a byword for implausible slightly ridiculous stories. Still for almost twenty years battles raged at the Volksoper between old fashioned operetta lovers and musical adepts, a lot of older people despising the American novelties. But the generations who had known princesses, counts and even emperors who played such important roles in operetta disappeared and younger people couldn’t simply believe anymore in stories of noble sons running the danger of being desinherited while courting a dancer. With My Fair Lady the musical started its triumphant road to success. It is ironic that today Show Boat and Gräfin Mariza, Kiss Me Kate and Das Land des Lächelns are thought to be classical music while official recordings all employ singers with fully developed

operatic voices, a far way from the dancing and singing actors (instead of the operatic acting singers) who once created them. Listen to Hubert Marischka himself and you will immediately realize how much the cultivated voice of Richard Tauber changed the whole operetta scene. Nobody nowadays will accept a Marischka or a Johan Heesters voice anymore, used as we are to Tauber, Wunderlich, Schock and Gedda.

There is an interesting coda in the book on the importance of operetta in the GDR. The communist thugs in power wanted to keep “capitalist” (Anglo-Saxon) music as long as possible in the cold and very much supported the creation of operettas in the best social realistic tradition; a policy they already relented from the seventies on as they didn’t succeed in jamming Western radio stations. Nevertheless some 200 new operettas were created and up to now only one survived the fall of the regime. All in all, a fine and interesting book though not cheap at all. And one should not take too seriously Kevin Clarke’s chapter on “operetta and pornography”. Erotic some operettas were. I remember too well the many operettas I attended to in my youth as my father was a member of a fine amateur company. During the fifties some of the themes were still risky as marital fidelity and religious devotion were not always the highest aim of the heroes ( Lehar’s Paganini, countess Lisa who abandons her husband Sou-Chong or The Tsjarewitsj who lives with Sonja without the bonds of holy matrimony and in Dostal’s Manina the queen even has a bastard son from her tenor-lover). In some operettas the sopranos even showed a bit of leg (Die Bajadere and Giuditta) and therefore the catholic newspaper in my Flemish city never published a review so as not to stimulate sin. But even catholic newspapers didn’t call Giuditta or Frau Luna (some leg too) pornographic.

Jan Neckers