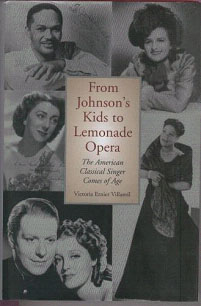

From Johnson’s Kids to Lemonade Opera

The American Classical Singer Comes of Age

By Victoria Etnier Villamil

Northeastern Press Boston 2004, 332 pp

I cannot help but thinking that the most important sentence in this interesting book is the following one: “It would be a pleasure to say that among the young Americans some new potentialities of world-shaking capacity were revealed. Unfortunately that is not the case.. On the contrary singers whose appearance in principal parts were justified neither by voice nor achievement were repeatedly given leading roles which in former years at the Metropolitan would only have been bestowed upon those indubitably worthy of the honour.” The author of these words is one of the most famous critics of the Times, Olin Downes and right he is. Though the author of this interesting book doesn’t time and again repeat the old story of fine American singers who have to give way to some not so fine foreigners, the theme nevertheless is somewhat lurking in the background. Therefore I think it a little bit of a pity that not much more space is devoted to the two singers who could easily sing rings around even the best of those foreign (almost always Italian) singers: Sophia Cecelia Calos as her passport stated and Freddy Cocozza. The first one is the big miss of Johnson though of course he and his assistants were right to detect some weaknesses in the vocal armour of young Mary Callas as she called herself. The second one is even worse as Freddy Lanza had an American career and I would gladly have known if Johnson ever took pains to listen to one of the greatest tenor voices of the last century.

Therefore we have to do with the real Johnson’s kids and with the exception of Merrill and somewhat less so Tucker, they couldn’t really compete on the same exalted level with the very best Europe had to offer. Nevertheless, a small, indeed sometimes a very small step lower, singers like Steber, Kirsten, Peerce etc. were interesting and exceptionally fine singers and our collections would be much the poorer without their contributions. But the real interest of the book lies in the fact that it follows the career of many singers who up to now are to most Europeans only a name or at its best a few lines in an old issue of Opera News. All at once a lot of these names we know from chronologies get a career and most of the time a face (many fine photographs; did Charles Mintzer help out ?)

The author writes well and avoids a lot of clichés on singing (she herself studied singing). Moreover she really succeeds in wetting our appetites and I for one would have appreciated a CD or CD-Rom giving us examples of those long neglected names. I’m sure most of us would have been in for a few surprises. Well, maybe not singers of “world-shaking capacities” but still interesting voices. Collectors who have bought “The American Opera Singer” by Peter Davies will do well to add this book to the ranks. They won’t be bored and I’m sure they will often return to it for references. There are some small mistakes but nothing serious. Lily Djanel was not French but Walloon and though Germaine Lubin was arrested a few times after the war she was released several times too and thus didn’t serve three years in prison.