Giuseppe DI STEFANO (24.7.1921 – 3.3.2008) PART ONE

In 1987 there was an Italian language course on Flemish and Dutch TV followed by a documentary. I proposed a programme called ‘Sei fuggitta è non torna più’ or the disappearance of a once inextinguishable breed: the Italian tenor. My Dutch colleague and myself collected footage by Caruso, Gigli, Lauri-Volpi, Schipa, Di Stefano, Del Monaco, Bergonzi, Corelli and Pavarotti. We also wanted to interview some former opera stars on the phenomenon. Magda Olivero and Renata Tebaldi cooperated without diffuculty and so we only needed a distinguished member of the breed itself. We started with the most uninteresting of them all though he would get us most publicity. We even got Pavarotti’s phone number and he was interested to participate but he would like us to check with his managerial shark Breslin. So we called him and he immediately asked what we were able to pay. Olivero and Tebaldi of course would have been ashamed to ask for money but Breslin was not. Well, we only needed half an hour of Pav’s time and could only give a symbolic sum of 800 $ though of course real ladies like our two sopranos would have been ashamed to ask for a single quarter. Breslin simply replied” no way” and slapped the phone down. Ok, we would look for a real great of the past . Once more Franco Corelli had disappeared and Bergonzi was filming somewhere in the south of Italy for Zeffirelli’s Young Toscanini. So that left us with Giuseppe Di Stefano. I phoned him at his home at Santa Maria Hoé and I immediately recognized the familiar voice who said “pronto”. Nevertheless I politely asked for Signor Di Stefano and to my surprise the voice told me he was not at home. ”What was the message ?” I told the ‘voice’ we needed the tenor for an interview and he replied he would tell the tenor. And then I added “pagato” (paid) and immediately the voice replied “son io, Di Stefano (I’m Di Stefano - as I knew all along)”. And what could he earn ? Well, 800 $ for half an hour. “Poco, poco (not much)” he replied but he consented anyway. On the actual day of filming he was hours late and he enthusiastically told how much he was in demand adding he was singing better than ever. People I tell the story to always shake their heads, speaking some words like “the old amiable rogue”. When one looks at his career and his road of broken promises and contracts which must have been small dramas in many a manager’s career, the word rogue or even crook without the “amiable” seems to be more apt.

Di Stefano was born on the 4th of July 1921 in the small hamlet of Motta Santa Anastasia near Catania in Sicily. His father, a former policeman, is a small shopkeeper. When “Pippo” is six, the family moves abroad (“a l’estero” are Di Stefano’s words) to Milan where the Di Stefano’s once more run a not very successful shop. Like so many Italian boys Di Stefano becomes a member of a church choir and is even promoted to the choir of the big Duomo. There he earns a few extra lire. A young student hears him singing a Christmas carol and is moved by the voice of the adolescent. He introduces Di Stefano to opera and takes him to performances at La Scala: Turandot with Lauri-Volpi and Poliuto with Gigli. Di Stefano likes Gigli more. The young man starts singing in cafés, restaurants and movie theatres and a few opera lovers take an interest in hem. They agree to invest in his career. For a few years he seriously studies the rudiments of singing with a former member of the La Scala chorus. But in Di Stefano’s opinion everything is moving too slowly and carefully. He wants to sing canzone and arias and he switches to the famous former baritone Luigi Montesanto. At that moment signor Mussolini intervenes and sends Di Stefano an invitation to join (together with millions of other youths) the army. Di Stefano has always told the story that his battalion is ordered to assist the Germans at the Russian front. The regimental doctor however thinks a good tenor is more important to Italy than a bad soldier and writes him a certificate. It is probably one of Di Stefano’s many lies and inventions. In reality his less than perfect health at the time is probably the real reason. Anyway, when he is off service he continues singing in bars and cafés using the name of Nino Florio; a typical Di Stefano joke as he well knows this is a brand of Sicilian wine. In September 1943 life takes a turn for the worse when Italy signs an armistice with the Allies. The Germans realize they will probably lose the peninsula and invade the country. Everywhere they round up Italian soldiers and send them to war prisoner camps in Germany when after a month of doddering the Italian government declares war on Germany. Di Stefano succeeds in escaping to Switzerland and is put into a refugee camp. He sings a lot and makes quite an impression on the camp. An Italian priest who takes care of the refugees is impressed and introduces the young tenor with the artistic director of Lausanne Radio; another Sicilian. Di Stefano sings at an audition and is engaged on the spot. Therefore he often gets permits to leave the camp to perform in Lausannne. His first concert is in January 1944 and he sings popular Italian songs. He has to learn a lot and he is supervised by legendary conductor Otto Ackermann, a stern taskmaster who teaches him to sing with an orchestra and to study scores. Di Stefano sings several radio-performances of operas: Elisir, La Cambiale and Tabarro and he continues concertizing as well as radio audiences ask for more. One of his admirers is a rich and somewhat older Russian lady and she asks him to record a number of opera arias and songs. She pays him 50 Swiss francs per record and as a book illustrator she paints him as the prince in a book of tales. Many years later Voce del Padrone will once more print these paintings on a reissue of those songs. And it is quite clear that Di Stefano didn’t limit his services to singing.

With the war’s end the tenor returns to Italy and he will come back to Radio Lausanne for a performance in French of Lehar’s Paganini; a contract signed before the end of the war. The records reveal an almost unbelievable beautiful timbre, rich in colours, with a fine legato and as one admirer writes: “ a tear in the voice without being tearful”. The young Di Stefano has the charm of Carlo Buti but the sound is more manful, more operatic and it can easily compete with the illustrious beauty shown by young Gigli and young Tagliavini. This is clearly a voice that will go for a world career. With hindsight it is of course easy to hear the weaknesses as well: some open sounds, covering is not Di Stefano’s method of singing, and a passaggio that is more conquered by young ardour than by technical proficiency.

|

|

Was this record actually ever released? Surely one of the rarest x-mas records ever. |

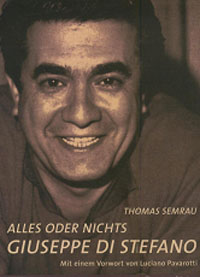

His biography is still available |

Back in Italy Di Stefano once more contacts his former teacher Luigi Montesanto and asks him to launch him into a career. Montesanto thinks the tenor could well use some extra-lessons but at the same time turns himself into Di Stefano’s manager at the unheard rate of 50% of all the singer’s earnings for the next ten years (a friend-lawyer will help Di Stefano to end this contract after six years). Montesanto is even so nice to try and give the tenor some extra-lessons but this Di Stefano hates. He already considers himself to be an accomplished singer and manager or no manager is trying to get himself a début in opera. In the meantime he earns a few lire by singing in night clubs and between movies in movie houses. He again uses the name of Nino Florio. He even records six songs as Florio. Montesanto realizes what kind of guy Di Stefano is and he doesn’t want to loose the goose with golden eggs. So he succeeds in having the tenor make his début on the 20th of April 1946 as René des Grieux in Massenet’s Manon (Italian version of course). I don’t think that Montesanto had extreme difficulties in trying to convince opera managers to engage the young tenor. All of them immediately realize what a super talent has appeared and as opera calendars are not yet decided upon three years but often only three months in advance invitations come in almost immediately. The Dante in Ravenna, the Politeama in Genua (the Carlo Felice is still in ruins), the Communale in Bologna and La Fenice in Venice want to hear him. He widens his repertoire with Sonnambula, Amico Fritz, Rigoletto, Traviata and Pescatori di Perli. Only eleven months after his début La Scala already asks him for another Manon though he has to restudy the role for 14 days at a stretch with Anton Guarnieri. There is a live recording of this performance and the house comes down after his “Il Sogno”. That success means too he can enter the profession without having to struggle for years in smaller houses or with travelling companies. La Scala immediately asks him back for Mignon where once more his success is overwhelming (though Simionato and Siepi too earn more than just a bit of applause). At the same time his name becomes known to collectors as he records a batch of arias and songs for HMV in London. La Scala has found its new tenor for lyrical roles and they offer him a new production of Pescatori (Pêcheurs de Perles) for the spring of 1948. Di Stefano duly signs the contract and then almost immediately breaks it when the Metropolitan has a better offer. His reasons are quite original. He says he still feels too inexperienced to sing in a house where the shades of Pertile, Merli and Gigli are still in the wings. At the Met the shades of De Reszke, Caruso, young Gigli, Martinelli and Lauri-Volpi are probably more friendly. In reality Italy is slowly, very slowly recuperating from the war and the Met pays better and life in the US is so more promising. The new general manager of La Scala, Ghiringhelli, promises Di Stefano he will never sing again at the theatre: the first such a promise in a long row that will not be kept by many a theatre boss. At the Met Di Stefano bows for the first time as Duca (with Warren). Though not all critics are enthusiastic most recognize a new major talent and the public is immediately won over. And among the public the ladies are very much charmed by the dashing young tenor. Di Stefano strictly believes in the old tenor wisdom of no sex before a performance but after one it is different and he becomes very much a ladies man. One American girl, Maria Girolami, succeeds in marrying him in 1949. She will give him three children: Luisa who dies tragically young, Giuseppe and Flora. America means not only the Met but the whole hemisphere as well. He is especially welcome in Mexico where the rich are very rich indeed and the tenor becomes a special favourite. Happily for us radio broadcast are many and therefore we can hear him in Traviata and Gianni Schicchi at the Met and Rigoletto and Manon in Mexico (all in 1948). Next year brings us three magnificent performances in Mexico as well: Werther, Mignon, Favorita (all with a splendid Simionato). That is the year too the new general manager-elect of the Met hears him in Faust which is broadcasted as well. Di Stefano uses a miraculous messa di voce on the high C in ‘Salut demeure chaste et pure’ and in his memoirs Rudolf Bing tells us this was the most beautiful sound emerging from a human throat he ever heard.

For four years the Met is Di Stefano’s main opera house. He only returns to Italy for holiday and summer performances at the Verona arena. He is the Alfredo of both Renata Tebaldi and Maria Callas during a famous South-American tour in 1951 where both ladies start their feud. In 1952 he is the partner of Callas in Mexico for several weeks in Mexico and we have to thank radio for live performances of Puritani, Rigoletto, Tosca, Lucia and Traviata. When Callas returns to Milan she urgently discusses a new production for 1953 of La Gioconda with Ghiringhelli. All her career the American soprano wanted good tenors at her performances as she shrewdly and probably instinctively realized that the better the cast the greater her own renown would grow. She is impressed with Di Stefano’s generous singing and vigorous acting and she pleads with Ghiringhelli to lift the ban. The Milan boss relents and offers Di Stefano a try-out as Rodolfo in La Bohème in December 1952. The tenor readily accepts and is glad to be home again as the results of the war are finally disappearing in Italy and La Scala once more pays more money than the Met. Moreover he is not entirely happy any more in New York. He has just received a letter from Bing offering him a flattering opening of the 1953-1954 season as Faust. So far, so good but then Di Stefano asks to skip the rehearsals of the new Met-La Bohème because he can sing a few extra performances of the same opera at La Scala. Bing doesn’t accept this and sends a scathing letter telling the tenor: ”it seems that you are perfectly happy with the ridiculous antics that usually pass on our stage for acting.” And “I do not believe that anything of what you have done so far in the way of acting will be acceptable”. And Bing ads insult to injury by telling Di Stefano “believe me you are not quite on the right way yet.” Now one wonders if this is the way one should speak to someone who just scored a triumph in Mexico where he is considered to be a half god and who as most Italian top tenors thinks of himself as a full god. The end of the story is predictable. Di Stefano sends in a plea he is ill and the Met’s Milan representative, Roberto Bauer, can assure Bing that the “sick” Di Stefano is performing at La Scala. Bing is livid, ends Di Stefano’s contract and starts the procedure to ban him on all stages in the US. As “never say never again” is the slogan of all opera managers he doesn’t continue with the procedure.

In the meantime Di Stefano is perfectly happy. He earns big bucks at La Scala and he doesn’t feel unhappy at all he is thrown out of the Met as he correctly assumes that Bing wants his singers to rehearse all the way to Tokyo and rehearsing acting is a thing many a tenor hates. The tenor is even rewarded for his undisciplined behaviour. He is a success in Bohème and in Gioconda while at the same time EMI-producer Walter Legge is looking around for a good tenor. Legge doesn’t know all that much of Italian opera but as the senior producer at EMI he knows he has to compete with Decca and RCA. He is married to Elisabeth Schwarzkopf who regularly sings at La Scala so that Legge gets some knowledge of its repertory and its stars. EMI has lost the race in the emerging LP race to Decca which after some initial try-outs now has a regal couple in Tebaldi-Del Monaco. Legge signs up Maria Callas for Columbia, one of the two EMI-branches (the other being HMV). Due to his Scala-performances Di Stefano has the attention of Legge who has at last found his tenor for complete performances on Columbia and HMV (Madama Butterfly with De los Angeles, Traviata with Stella). In 1953 alone the new Columbia-couple records four operas: Rigoletto, Lucia, Puritani and Cavalleria (Callas substitutes for Fedora Barbieri). In addition Di Stefano records his first of many Columbia-solo-albums. Summer months will be from now on mostly devoted to recording. In retrospect we can say that 1954 is his last year as a lyric tenor. Collectors still dream of a never turned-up live recording of those great La Scala performances of Eugene Onegin. Vocally there was probably never a more perfect cast than Tebaldi, Bastianini, Di Stefano. From the beginning of 1955 the tenor will start with his vocal suicide.

Jan Neckers, Operanostalgia