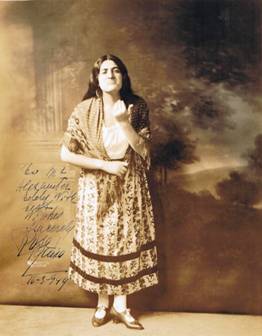

ROSA RAISA’S MALIELLA IN THE JEWELS OF THE MADONNA

On December 9, 1917 Rosa Raisa of the Chicago Opera performed her first of forty-three Maliellas with that company, an opera mounted almost every year for her and husband Giacomo Rimini until 1930, both in Chicago and on its transnational tours. Even before then Chicago Opera’s General Director Cleofonte Campanini had a special affection for this work and he had produced it forty-four times between 1912 and 1916 in Philadelphia, Chicago and on tour with American sopranos Carolina White and Helen Stanley most often as Maliella. Of that December 9th performance with Raisa and Rimini, the critic of the Chicago Herald thought “Raisa’s reading of the wayward heroine was somewhat more Italianate than Miss White’s had been. It was powerfully set forth; gusts of passionate feeling tore through it, and the somewhat hard angle to Malellia’s character was accentuated.” A month later the impact of her performances in this opera elicited from The Chicago Tribune’s critic: “Miss Raisa’s Maliella is something to align in the memory with Calvé’s Carmen, Ternina’s Tosca, Garden’s Louise, and Fremstad’s Götterdämmerung Brünnhilde.”

The Chicago Daily Journal was more detailed about her impersonation: “She knows the value of effective color combinations in costuming. The brilliant red of her first appearance struck the note of the character in a way that none of her predecessors have been able to do. She was a young savage, abounding in energy, She sang, and the chorus and orchestra were carried along with her. She lashed out at a Camorrist -- Désiré Defrère was playing the part -- and the resounding slap was one that will hardly make him envied for his role. She adopted a rolling low-class walk, which is by no means Miss Raisa’s normal gait on the stage. The feeble uses of type will not permit a reproduction of the savagely rolling r’s of hissing, spitting sibilants of her speech, still less can they indicate the gorgeous voice that dominated anything and everything within hearing. She was not a nice girl, this handsome, clawing, half-civilized tiger cat, but she was a fascinating study. For the way Miss Raisa brought about one thing she deserves extra credit and thanks. That was the extremely tricky, extremely unpleasant ending of the second act. Here she managed to convey definitely the course of the plot, at the same time without giving offense and with a pictorial value. The combination of effects is something no Maliella has been able to do since the opera was first staged here.”

In winter 1918 Campanini gambled big by bringing his Chicago Opera to New York for a three week season at the Lexington Opera House (Lexington Avenue and East 51st Street). For these three weeks Chicago’s world-class performances were in daily competition with the Metropolitan Opera. New York audiences knew very well both Mary Garden and Nellie Melba and and were looking forward to the much-heralded Amelita Galli-Curci; her fame was world-wide after her sensational November 1916 Chicago début and the resultant Victor records. Raisa, his fourth star was not so well known, although some of the “in” people had heard about her through the grapevine. Yes, there was an opera grapevine even then. Garden and Lucien Muratore opened the season with Février’s Monna Vanna and the second night was Raisa’s début in I gioielli della Madonna.

The New York critics already knew the opera from previous Chicago-Philadelphia Opera Company visits to New York where they performed at the Met on nights when the Metropolitan played out of town, and they did not have a high estimate of the Wolf-Ferrari work. Some critics calling Jewels, mere “Paste!” One New York opera critic qualifying his statement that Raisa was not completely satisfying, “but the fibre of the voice is so fine, so essentially dramatic and warm, and her musical interpretations governed by such excellent taste, that coming into New York’s operatic midst at a time when there is no first rank artist of her kind, she is rather more than welcome. The gratifying and unusual element in Mlle. Raisa’s voice is its elasticity, With a phrase delivered with an intensity and wealth of power truly remarkable, this young woman can -- and does, a phrase or so, deliver a mezza-voce tone which is as light and melting as the most lyric soprano. The newcomer, whom New York scarcely knew, even by reputation, has personality: a degree of physical buoyancy that might be termed “pep.” In a word, she sang Maliella last night to nearly the last ounce, and her reappearance should bring to hear and see her many who want what she can supply.

The most respected New York critic on all matters vocal, W. J. Henderson, writing in the Sun thought, “She is the dramatic soprano of the company, and the reports which reached us from Chicago were that a new star of the first magnitude had arisen. Miss Raisa proved to be a singer of excellent qualities. Her voice is full and rich and of large power. It is not perfectly equalized -- few voices are -- and the upper register is prone to openness. But it is so fresh and genuinely beautiful that it cannot fail to give pleasure to the hearer. Miss Raisa sang the music of Maliella with temperament and dramatic skill. Her impersonation as a whole had direct force and intelligence. And withal she is good to see.”

(Antonio Cortis as Gennaro)

(Antonio Cortis as Gennaro)

After the New York season the Chicago company went to Boston where Philip Hale in the Transcript had provocative thoughts on the opera and Raisa: “Boston has seen several Maliellas since this repulsive and sacrilegious opera with its generally vulgar music was performed here in January 1913. Mmes. (Louise) Edvina, (Carmen) Melis, (Elizabeth) Amsden, (Helen) Stanley and (Bianca) Sarroya, perhaps others whom we do not recall, there have been interesting performances of the opera with various tenors and accomplished baritones, but none of these performers was as dramatically engrossing as the one last night. Miss Raisa is indeed versatile as an actress and singer, Take her Aida, Isabeau and Maliella; mark how she gives character to each heroine. Her Santuzza is said to be equally remarkable. Not only does she truly impersonate in action and in repose, she characterizes in song. It would be difficult to say in which she excelled last night. Perhaps the most striking feature of her performance was the portrayal of her spitefulness toward Rafaele turning to passionate love -- love as this hot-blooded woman understood the word. Yet the scene in which she donned the stolen jewels and admitted the embrace of Gennaro with the name of Rafaele on her lips was marvelously portrayed. Here is a singer who can be fiery and ascetic, passionate and meditative, not merely an actress that incidentally sings, but a singer that is lyrical, dramatic, and imaginative.”

Chicago again brought I Gioielli to New York in 1922, this time at the Manhattan Opera House on West 34th Street. Henderson now thought “It may be noted that The Jewels of the Madonna has held its place in the Chicago list without challenge from the local institution, which might be indicative of a want of faith on the part of the astute Mr. Gatti-Casazza. The role of Maliella seems to be an essential item in the plans of Miss Rosa Raisa, who enjoys its distinctions season after season. Her impersonation has admirable traits. She looks well, acts with vivacity and at times energy, and sings the music in that far-reaching style which has made her so popular with operagoers.”

(Forrest Lamont as Gennaro and Carmen Pascova as Carmela)

A month later when the Chicago company gave performances in Los Angeles, critic Edwin Schallert in The Los Angeles Times waxed rapturously about the opera and the diva. “What person takes Jewels of Madonna seriously? What person cares about its plot or the people? Is not the eye filled with pictures? Is not the ear intrigued with music? What matters it who wrote it? Or whether it is great or small; pretentious or a trifle, sincere or just a conceit? The main thing is that it is delightful. At least the Chicago Opera Association made us think so. We believed it last night. We thought we were hearing lilting songs and rapturous melodies; we thought we were viewing Neapolitan seaside, and a Neapolitan carnival; we thought we were seeing merry pranks and festive peasants. And then -- perhaps we dreamt we saw death end it all, snuffing out all the gayety, all the mad merry illusion, as one would snuff out a Christmas candle.... The Chicago Opera Company gave it a presentation which lived up to serenest expectations. They brought all the color and radiance and buoyancy to the interpretation that this beautiful accomplishment of the composer, Wolf-Ferrari, merits... Jewels of the Madonna is not easy to give effectively. It needs the proper “mise en scene.” The Chicago company has perfected this detail. They play the opera with verve and abandon. They have made it one of the best in their repertoire. Of course it requires a singer like Rosa Raisa to interpret the role of Maliella, that second cousin of Louise and Carmen. It takes subtlety and fire to create a living impression of this hot-blooded and indefinable heroine. Too, it takes real singing with fine flourishes and a flash of pyrotechnics, to do justice to the vocal trimmings of the part. Miss Raisa seems to realize the tricks of this production. She does not hesitate to flash the full brilliance of her part in it before you. She flamed against the sunshiny festa, she glowered in the moonlit softness of perfumed garden. She dominated each scene with a radiant aura that captivated the beholder and held ensnared the eye seeing pictorial beauty...

(Rimini as Rafaele and Forest Lamont as Gennaro)

“Vocally she was at times resplendent. Her tones had a consuming warmth that reached out to enthrall the senses. She sent forth luminous shafts of tone that penetrate to the heart of admiration. There were, of course, moments when she wavered. Just a trifle in the higher peaks of the fioratura. I caught one such moment in the night scene, where she ascends the steps. A long and difficult passage she sings, that circles and circles like an eagle’s flight to the heights. Just a little edge of uncertain quality here for a second and then her voice rang clear once more.”

Schallert was clearly referring to that anticipated moment in the second act, best described by Karlton Hackett in a January 1927 account of a Chicago performance: “That cruel vocal stunt on the stairs in the second act she did with matchless assurance. She has to take an F sharp, then trill on it, and when the harmony tells you that that she is to go up to a high B for the finish, Mr. Wolf-Ferrari makes her take a totally unexpected high C and without a sound from the orchestra for support or to prove to the public that she has struck the intended note. The musical purpose was to express the fire of revolt raging within her. But the unprepared musical crash has let not a few learned pedants, who, alas did not know the score, to assume and assert that she had gone sharp whereas with the certainty of skill she had done exactly what the composer desired. The way of the great artist is hard with all the sharp-eared ones laying in wait to catch her in a fault. But last evening Miss Raisa could defy the whole crew.”

Henderson in his 1922 account of Raisa’s Maliella did not mention that Maria Jeritza, the Met’s new superstar, sat in a prominent box witnessing the performance. Perhaps Gatti-Casazza had urged her to check out this opera. This is significant as Jeritza would perform this opera at the Met in 1925 after some tough back-and-forth with Gatti. Although Henderson at that time was certain that Gatti-Casazza did not view the opera favorably, in fact, Gatti wanted to produce it for Jeritza as her 1925 vehicle at the Met. In the Met Archives there is documented this heated correspondence; on 9 June Jeritza wrote from Europe to Gatti’s secretary Luigi Villa “but must tell you that after having tried the role of I Gioielli della Madona I find that it does not suit me at all. It is absolutely for a very light or coloratura soprano and not at all suitable for my voice. It would be necessary to change the whole score and that would be too difficult. I had already about ten rehearsals but see more and more that the role is not for my heavy dramatic voice...I ask you to kindly tell Mr. Gatti that I would be very glad not to sing it at all.” Gatti was not to be deterred and reminded Jeritza that as his star soprano he would never ask her to do a rôle if he did not think she would be successful. He had as much riding on his judgment to do the opera as she did as a singer doing the difficult part. He was certain she would be sensational. He reminded her that she was reluctant to sing Fedora in 1923, and as he predicted, she enjoyed a big success. He was certain that her reluctance had to do with the very high tessitura and he assured her “Please study all that suits you in the rôle of Maliella and leave aside such things as you want to be modified. Such modifications will be made when you get to New York.”

An interesting element in this is that on 7 October 1924 it had been officially announced to the world press that Raisa was chosen by Puccini, still alive, and Toscanini, for the upcoming Turandot world premiere at La Scala. Jeritza was smarting from what she considered a snub as she was certain that Puccini had wanted her for the world premiere, but Metropolitan Opera and La Scala politics made this impossible.

The Met in those days double cast leading rôles in the event of an emergency. Jewels was placed in Rosa Ponselle’s contract as a rôle she should be prepared to perform, if necessary. Edward Ziegler, Gatti’s assistant wrote to him on June 25: “Have failed with Ponselle. She declares must rest her voice full month so that she could not possibly have time to learn Vestale and Jewels. Tried utmost to persuade her without success. Suspect she fears high tessitura.”

In any event Jeritza had a success with her Maliella, Henderson saying “Jeritza’s interpretation of the girl Maliella was a carefully planned one and faithfully carried out. There was scarcely a detail missing. She brought all of the artistic wealth of her Viennese background to the vixenish passion and abandon of the hot-headed Titian-haired virgin of the Neapolitan people, and it must be said that every step of the way was consummate art. I have heard the rôle sung better, as regards sheer vocalism, but this is an acting opera far more than a singing one and in order to portray an unbalanced, passionate young woman, Jeritza’s sometimes strident tones simply accentuated the pathology all the more.” Jeritza’s June 1925 denigration of the rôle, calling it a mere coloratura one, was clearly aimed at her rival Raisa. After the choice of Raisa for the Turandot world premiere they would hurl accusations at each other as to which soprano Puccini “really” wanted for that coveted assignment.

(the composer and his tomb)

(the composer and his tomb)

It is noteworthy that in 1937 when the Vienna Staatsoper mounted Der Schmuck Der Madonna Maliella was assigned to the soubrette Margit Bokor, a Musetta and Blondchen. When the opera was revived two years later, after Bokor emigrated from Austria, Maliella was performed by Helena Braun, an Isolde and Brünnhilde, and Elsie Schultz, an Aida and Tosca. The Bokor choice would seem to partially validate Jeritza’s estimate, but the Braun and Schultz choices clearly does not. To the extent that the opera was given around the world, Italy excepted, it was generally cast with spinto sopranos, with Raisa and Jeritza cast in the rôle due to their superstar stage animal qualities and their glamorous large voices.

Today, Raisa is famous for being the very first ever to sing the rôle of Turandot. Most opera companies in their program notes list the creators of rôles, and therefore her name is somewhat immortalized. Turandot is today more famous than ever for many reasons; its recognizable melodies having entered into the world’s popular culture. In her time Raisa was less famous for her Turandot (fourteen performances, La Scala, Buenos Aires and Chicago) than for her passionate Aida, her spectacular Norma, her empathetic Rachel in La Juive, and her dazzling Malellia. There were many sopranos in operatic history who achieved fame in Aida, Norma, and La Juive, but of the forty-nine rôles she performed during her career, Maliella was uniquely hers.

Charles Mintzer