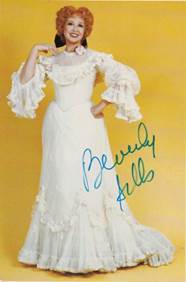

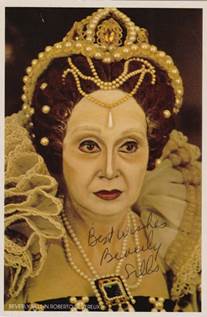

(early publicity photo)

(early publicity photo)BEVERLY SILLS A VERY PERSONAL TRIBUTE

(All photos courtesy Charles Mintzer collection)

(early publicity photo)

(early publicity photo)

Writing about Beverly Sills is not easy for me as I travelled an unusual trajectory in my “fan-relationship” to her from 1966 to just before her Met debut in 1975. I had heard her in 1956 with the New York City Opera in my hometown, Burlington,Vermont, when that company did some touring in the NorthEast (performances not covered in Martin Sokol’s great book with its chronology of the NYCO); the opera was “Der Fledermaus" (click here to listen) and she was the Rosalinda. I was impressed, so I filed away her name in my memory. When I moved to New York in the autumn of 1957 for graduate study at Columbia University I started “living” at the Met, and did not very often check out the offerings of the New York City Opera at the City Center, my loss! I guess one couldn’t engage all the musical riches New York City offered at that time. (author’s note: I just checked the newspaper of record in Burlington, "The Burlington Free Press," and that “Fledermaus” performance, part of the University of Vermont’s Lane Series, was given, not by the NYCO, as I assumed, but by a touring group of the San Francisco Opera Studio. I stand corrected for conflating this offering with the NYCO, an obvious assumption on my part).

I did hear Sills in the 1966 spring season of the NYCO at the just-opened New York State Theater at Lincoln Center in “The Ballad of Baby Doe" (click here to listen) with Walter Cassel and Ruth Kobart. That was a revelation and I became a fan and started following her career. In addition to her excellent embodiment of the character, it was her singing that floored me. I had heard many sopranos navigating “in alt,” taking incredible high tones, but she was easily singing poised pianissimo high D-flats in an ethereal way with perfect control. Months later my phone rings, and a very dear friend called me during an intermission of the premiere of “Giulio Cesare" (click here to listen) to inform me that history was being made, that Sills was giving a phenomenal performance and the “place was going crazy.” Needless to say I was thrilled with that report, confirmed the next day(s) in jaw-dropping reviews, the kind that launch a star career. The irony of it all was that Sills had been a fixture in the New York and national music scene for ten years already, but I had my “Met” blinders on.

We now know, from various memoirs and research, that Sills was to use her Cleopatra success to launch her star career. From Julius Rudel’s recently-published memoirs he relates that his advice to her, in the aftermath of her success, was to hire a top press agent. As Sills was independently wealthy she was able to hire the very best in the business, Edgar Vincent, whose list of clients was the “Who’s Who” of opera stars in America: Birgit Nilsson, Eileen Farrell, Rise Stevens, Shirley Verrett, Anna Moffo, and later Cecilia Bartoli and Placido Domingo. Over the next few years there were tons of articles and items in the media about the Brooklyn girl who fought her way to the top of her profession, that she had to deal with serious personal matters such as a deaf daughter and a son with serious physical and mental issues. As she was very articulate, gave substantive and funny interviews, she was a “natural” for the hype she bought. My own theory is that bought publicity and hype only work if backed by real talent.

I went over my own performance chronology and found that I heard Beverly in most of her post-1966 roles, up to 1976, over fifty-five times. I heard her in “Giulio Cesare,” “Manon,” “Faust,” her solitary performance of the three operas in Puccini’s “Trittico,” “Le Coq d’Or,” “Lucia di Lammermoor,” “Abduction from the Seraglio,” ‘Roberto Devereux,” “Traviata,” “Maria Stuarda,” ‘Contes d’Hoffmann,” “Norma,” “Ariodante,” “Anna Bolena,” “Puritani,” and “Thais.” I did not attend her Met debut in “Siege of Corinth,” but did catch a later performance, nor her “Don Pasquale.” I did see her “Thais” in San Francisco while visiting a friend who still retained a soft spot for her, and I did see her at the Met in “Traviata” conducted by Sarah Caldwell. I heard her Queen in “Les Huguenots” and Marie in “Fille du Regiment” at Carnegie Hall with the American Opera Society. I went to Hartford for her “Traviata” with Aldo Bottion and Chester Ludgen, Boston for her first “Norma” under Sarah Caldwell and Washington DC for the opening of the Kennedy Center opera house in Handel’s “Ariodante” with Tatiana Troyanos. In Boston for the “Norma” I remained in the theater after the long applause died down, and went on the stage where she greeted her admirers; the theater had no green room. She was very happy with her success and when someone asked her how difficult a sing was Norma, she thought that Violetta was as long and as difficult; she thought Elisabetta in “Roberto Devereux" (click here to listen and watch) took more out of her.

I also heard her in concert many times, twice with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, one of which she shared the spotlight with Eileen Farrell in arias and duets by Handel. I was at the famous Carnegie Hall performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra of “Ariadne auf Naxos" (click here to listen and watch)with Claire Watson, conducted by Erich Leinsdorf, concerts at Philharmonic Hall and Brooklyn College, and the above mentioned concert performances of “Huguenots” and “Regiment.” In 1971 she participated in a concert sponsored by the International Piano Library at Hunter College where she sang, with her longtime accompanist, Roland Gagnon, a medley of snatches of stitched-together arias associated with her, subsequently released on the “pirate” market as “Sillsiana.” In the late 1960s and early 1970s she was a frequent guest on Johnny Carson (click here to watch) and Dick Cavett TV talk shows. For a while she carried on a dialogue, not in person, but on alternate nights, with Rudolf Bing, Sills pushing the “elitist” theme about Bing’s refusing to hire her, a made-in-America superstar. This TV dialogue spilled over in the mainstream newspapers and became a talking point among persons not familiar with opera politics. It went as: “That European Bing who runs America’s top opera house won’t hire America’s best-known and loved soprano, even minimizing her talent with notion that he didn’t need a Brooklyn girl impersonating the Queen of England.”

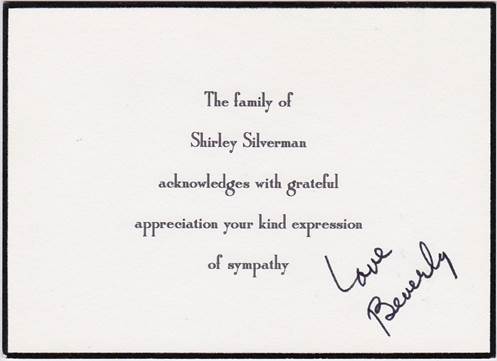

I really enjoyed some of the positive chatter about her, but there was also controversy as many an informed opera lover was not buying the Sills legend then being aggressively marketed. I remember being impressed that both TIME magazine and NEWSWEEK magazine had given her their covers at a time when those mainstream magazines were cutting back on boosting “cultural” icons. But by 1971 I sensed that a backlash was setting in, that at the height of her fame the inevitable ravages of time were reflected in somewhat diminishing vocal powers. I started to notice some atrophy in the highest tones, some wear-and-tear on the instrument itself, a sense that she was pushing her modest instrument beyond what the higher powers intended. I continued to check out her performances. In the early 70s I ran into her mother during an intermission at Alice Tully Hall where Beverly was performing with the Chamber Music Society. Her mother recognized me as a fan who often went backstage after performances and she approached me and we made some small talk. I told her I was worried that Beverly had undertaken too ambitious a schedule for in one week she sang a Mozart concert at Carnegie Hall with the Cleveland Orchestra, “Roberto Devereux” two nights later at NYCO and now these concerts with the CMS. I told her that Beverly omitted the high E-flat in “Vorrei spiegarvi, oh Dio,” which she took effortlessly on her recording a year or so before; her mother said, as only a mother can, “Beverly still has E-flats.” A friend of mine, to whom I related this anecdote, will often say in conversations, not remotely related to singing, but to suggest absolute certainty about something, “Beverly still has E-flats!” When her mother died many, many years later, I sent Beverly a condolence note and mentioned the anecdote suggesting her mother’s pride and certainty.

I thought that Beverly’s voice was not one of the great natural instruments but a very good and beautiful one that allowed her to go beyond sheer voice in communicating operatic and song emotions. Technically, I thought her superb: wonderful legato and breathing, excellent musical instincts, until overuse took away her ease on top, a wonderful upper extension, dazzling coloratura skills, persuasive trills produced at will, etc. Although you could always hear her, the voice was not notably large. Her taste in ornamentation was called into question, mostly about over-ornamentation, verging on exhibitionism. When her first aria recital came out on the Westminster label, the embellishments were almost too much and were the only negatives mentioned in an otherwise praiseworthy effort. There was an element of “hard sell” that I think made some connoisseurs a bit uneasy. But, in every opera in which I heard her, she usually produced excellence in the high points. Who can forget the slow arias in “Giulio Cesare,” the Cours l’Reine scene in “Manon” and later the St. Suplice scene, the Lucia Mad Scene, the “Martern aller Arten” From the “Abduction,” the final scenes in the three Donizetti Queen operas, and especially her confession scene in “Maria Stuarda,” the three differentiated heroines in “Contes d’Hoffmann”? I heard a “Manon” performance where she not only sang an effortless “Gavotte” but added the “Fabliau,” the alternate aria Massenet composed for soprano Georgette Brejan-Silver, but she gave both as a vocal “tour d’force.” So many good memories. Then around 1974-75 I dropped Sills; I didn’t want to celebrate her vindication being given an opening night at the Met as a token of her importance. Yes, she had become important, but I wanted to be counted out of the celebration. It took me a few years to re-evaluate her and my unusual journey. I did watch on national TV her farewell concert with so many stars, not only of opera, but of Broadway celebrating her. I continued to occasionally read about her achievements in opera management and fund-raising; she was constantly getting press notice for her celebrity. I felt bad when my friend Bob Tuggle, Archivist of the Met, told me that it was whispered at the Met that she was very, very ill. Although my love affair, such as it was, had ended, I still had good memories of my ten years being smitten with her art and fame. I never felt that Sutherland or Caballe, her contemporary rivals were better overall, even though both their instruments were objectively more remarkable. I felt Sills compensated with her musicality and technique over Sutherland’s larger sound and remarkable high extension or Caballe’s glamorous sound. I thought Sills a more remarkable artist and stage figure and a communicator. No one ever accused her of “mushy” diction or of being unprepared. Until the end of her life she was in the spotlight, the invariable hostess on TV, especially the “Live From Lincoln Center” series. She was a good interviewer, but she always injected her career and personal anecdotes into her interviews, not always accurately. I guess she represented the new America, breezy, sunny, chatty, glib, but also good natured. In spite of all the negatives I have related, I do miss her as she was a very special artist.

Charles Mintzer, September 2017