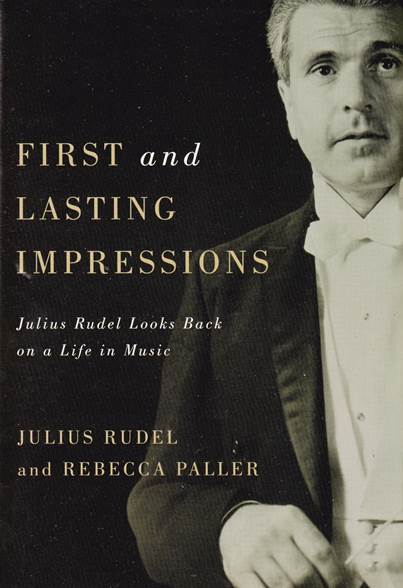

Julius Rudel and Rebecca Paller: FIRST AND LASTING IMPRESSIONS, Julius Rudel Looks Back on a Life in Music.

University of Rochester Press; 2013

193 pages; US $49.95

(all illustrations courtesy Charles Mintzer collection)

Review by Charles Mintzer

Ninety-Two-years-old Julius Rudel has finally authored his memoirs with the help of Rebecca Paller, a curator at the Paley Center for Media in New York City. His multi-faceted career covers many areas of the classical music world, especially opera. As a young man in his early twenties he was present at the birth of the remarkable New York City Opera; eventually he became the company’s music director and general manager; he worked on Broadway; he ran the Caramoor festival for fourteen seasons; he was music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic (1979-1985); he opened the Kennedy Center in Washington, the Wolf Trap Festival, championed American opera composers; and, after all that, he enjoyed a fine thirty-five year career as a respected conductor in both Europe and America, with 268 performances conducted at the Metropolitan Opera alone. And he is still inextricably linked to what gets one of the longest chapters in the book: “Giulio Cesare” and the Sills Phenomenon.”

This slender 193 page book is on the expensive side (US $49.95) but available on line for almost half that. The photos (not on glossy photo paper) are very well selected and Rudel authored the informative captions in the first person which tell his remarkable story. A Rudel chronology of his performances would be a book as big in itself; the only appendix at the back is a detailed listing of his three all-American opera seasons backed by the generous funding of the Ford Foundation. It is clear I think that Rudel considers these seasons the top achievement of his career, or if not the top, very close to it.

Forced in 1938 to leave his native Vienna due to the vicious anti-Semitism that was institutionalized after the Anschluss, he arrived in New York with $17.00 to his name. For five years the high school dropout, living with relatives in the Bronx, worked in menial jobs in Brooklyn, Queens, and Newark earning about $2.00 a day, but studying music simultaneously (composing and conducting) on scholarship at the Mannes School of Music. In 1943 the City of New York acquired the bankrupt Mecca Temple on West 55th Street, and the visionary mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, decided to use the 3,000-seat theatre for concerts, dance, and opera at very low prices that anyone could afford. In that period there was an amazing influx of European musicians as well as out-of-work talented Americans to draw upon. The opera component was put in the hands of the Hungarian-born conductor, Laszlo Halasz(1905-2001), then director of the Saint Louis opera. Rudel applied for a job as a “jack-of-all-trades” pianist, and eventually Halasz picked him, after several auditions, from the many aspirants. The pay was almost non-existent and the working conditions bordered on the unbearable, but Rudel was so ambitious that he put his pride aside and made himself invaluable to the nascent opera company.

The first seasons of the New York City Opera were short, but ambitious. In the earliest years of the company there was an eclectic mix of young American singers needing a showcase and some veteran stars wanting to assist the young company. Martin Sokol’s history, The New York City Opera, An American Adventure with complete Annals, details chronologically this amazing enterprise. Rudel slowly went from a rehearsal pianist to conductor. He had learned his conducting skills at Mannes, and made his conducting debut in Johan Strauss’ The Gypsy Baron with Marguerita Piazza, Elizabeth Wysor, William Horne and Carlton Gauld. He conducted every season from the Fall of 1944 to the Fall of 1980. The company had split seasons, Fall and Spring. In between the two opera seasons the theaters (at first the City Center, and after 1965, The New York State Theatre at Lincoln Center) hosted George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet.

Rudel did not care for Laszlo Halasz the man, who was both mercurial and despotic, never really appreciating his dedication and skills. He thought Halasz was a remarkable musician, but as a conductor he did not have a clear beat, and this led to unfocused performances. I found it of some interest that the great Giorgio Polacco (Metropolitan and Chicago Operas and others), then living in retirement in New York, gave Rudel both professional mentoring and strategic planning ideas.

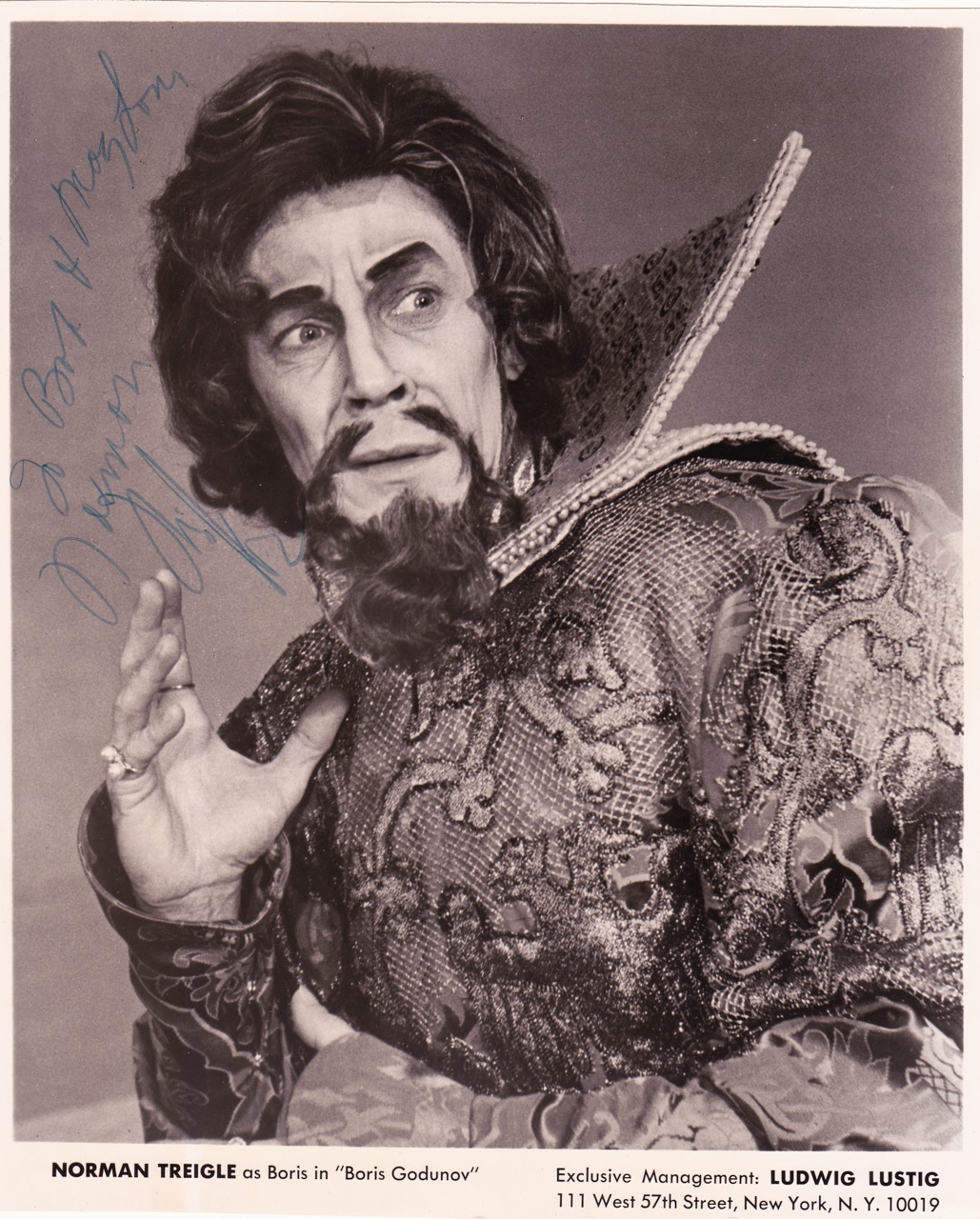

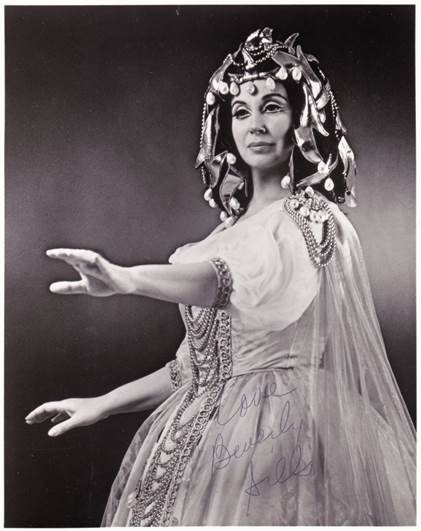

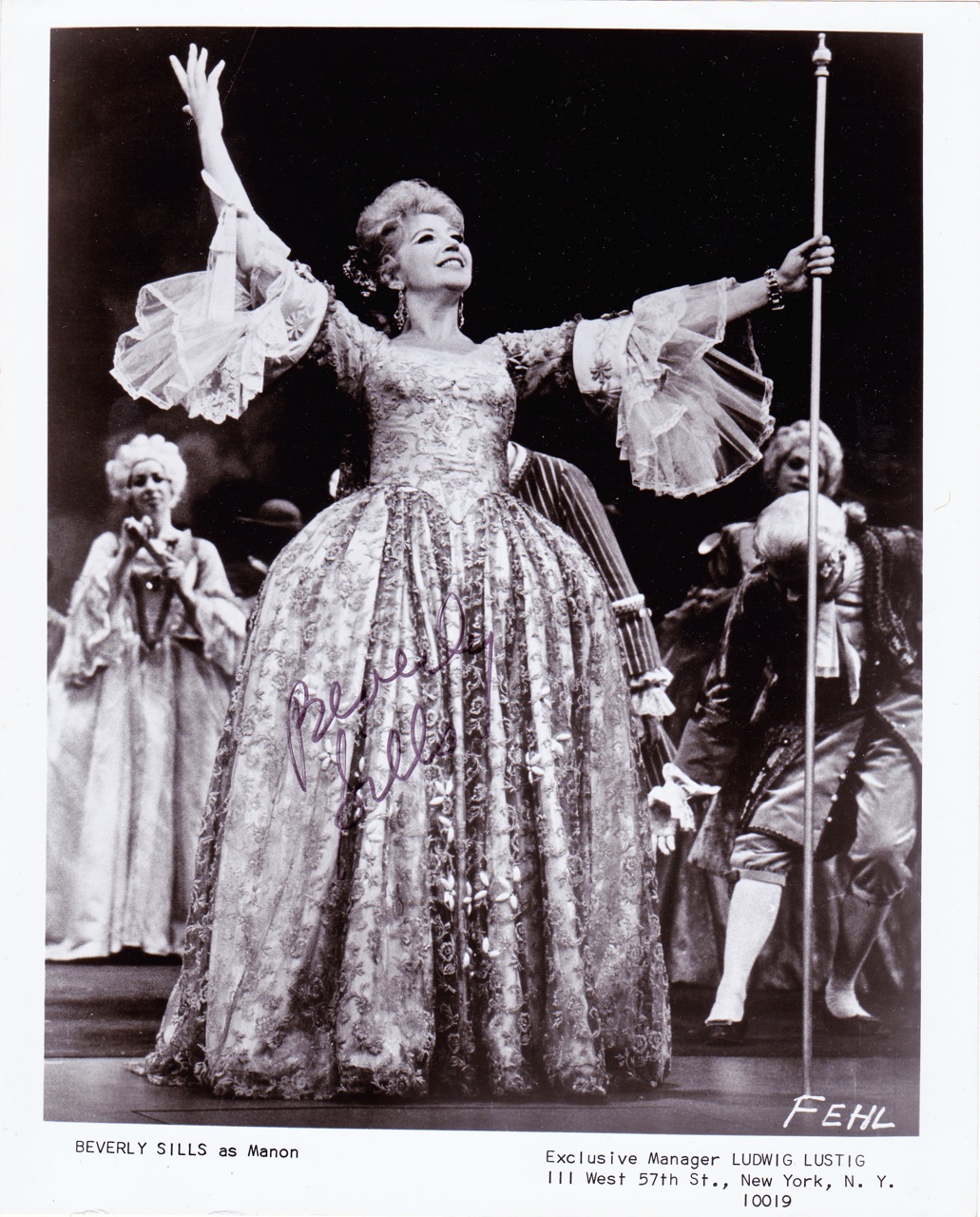

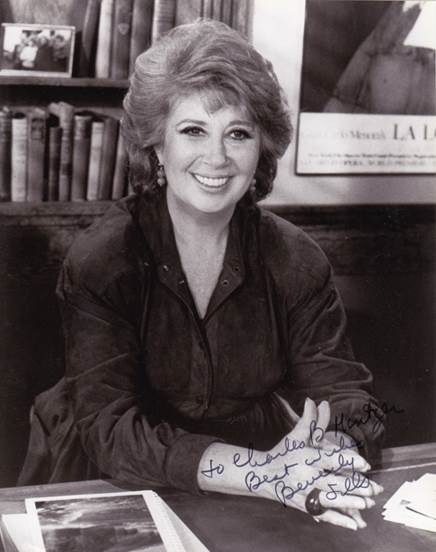

I think the most anticipated chapter in the book is Rudel’s final “take” on the Beverly Sills phenomenon. After the move to the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center, Rudel decided to give Handel’s Giulio Cesare, as a vehicle for Norman Treigle and Phyllis Curtin. Phyllis was ok with the planned dates of the performances, except the last two. In this period Sills “discovered” the opera and wanted to perform it, feeling that it was a natural fit for her type of voice and coloratura skills. Rudel was in a quandary as Sills had been with the company for nine years and was always a reliable trouper whereas Curtin was now less exclusively a City Opera artist, singing at other theaters including the Met. An anecdote that has gone around (Rudel recounts this with a non-malevolent spin) has it that Sills told Rudel that if he didn’t give her the production, her wealthy husband, Peter Greenough, would rent Carnegie Hall and she would give a concert including the five Cleopatra arias. Rudel succumbed to this pressure and gave Sills the role, thus alienating Curtin. Rudel says “All these years later I regret how things were handled with Phyllis. She is a marvelous, intelligent performer – and this incident put a rift in our friendship that has taken a long time to heal.”)

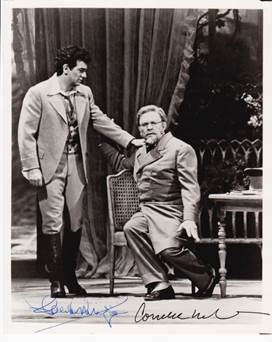

(Curtin and Treigle as Boris)

(Curtin and Treigle as Boris)

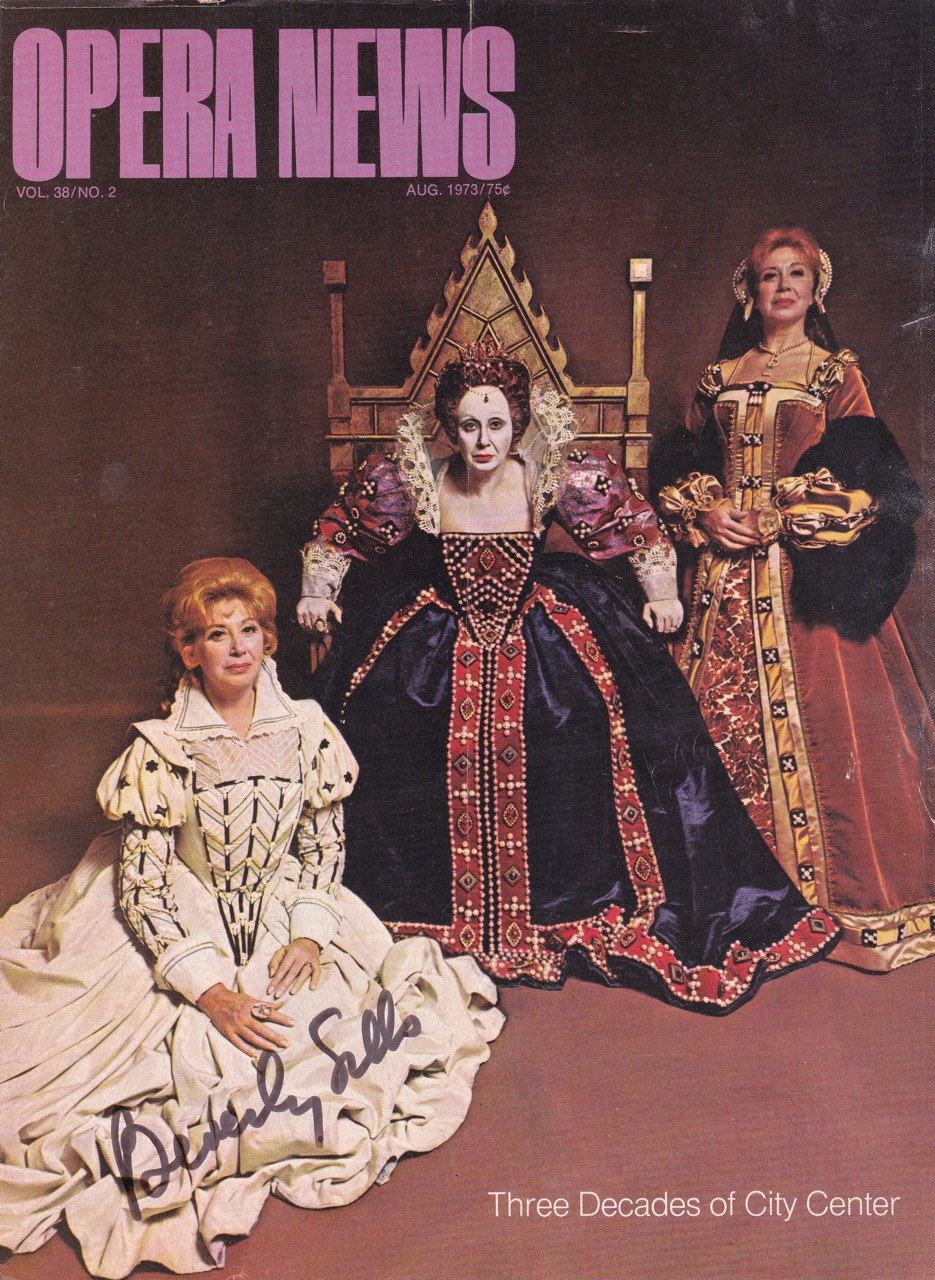

The rest is of course history for Sills had a triumph, the stuff of legend. Rudel recounts that one of the most prescient things he ever said the day after the premiere when the company was savoring the brilliant Sills reviews, he advised her to hire a press agent. Not only did she hire a press agent, but she hired the very best in the business, Edgar Vincent. Sills turned out to be a “natural” for publicity: she was attractive, articulate, witty and able to hold her own in interviews, she was from Brooklyn, she had the sad saga of her two children born with serious birth defects, she could think on her feet, and she was at the height of her vocal gifts. One can cringe and be dismissive of “bought” publicity, but hyperbole only really works if it is backed up with “real” talent. The downside of the Cesare brouhaha was that Treigle resented the reviews that questioned his suitability for the role, lacking, many indicated, a true bravura technique needed for Handel. And although Treigle acted as though he and Sills were still “brother and sister” in their original mission to give opera in America a true musical-dramatic lift, in fact, Treigle saw an opera, allegedly at first given to showcase him, become the vehicle that catapulted Sills to an operatic superstardom that he did not share. A personal note: At the time of the Met and City Opera opening festivities in September 1966, I recall that the big “story line” was that it was going to be the showcase for Maureen Forrester’s debut on the operatic stage; the estimable Canadian contralto had achieved a level of fame as a concert and oratorio singer. You can imagine the surprise when my phone rang after the second intermission and a very dear friend called me at home to tell me that they were in the presence of a genuine “sensation,” referring to Sills. Parenthetically, regarding the so-called Sills/Treigle “mission” to avoid a star system, Rudel gibes that years later when Sills became the manager, she brought in Victoria de los Angeles as Carmen and Grace Bumbry as Abigaile to embellish the company’s star power.

About the Giulio Cesare, Rudel, forty-five years later, admits that the version of the opera he crafted would not be acceptable today. He made substantial cuts, re-ordered the sequence of the arias, and put out a version that Handel scholars view with disdain.

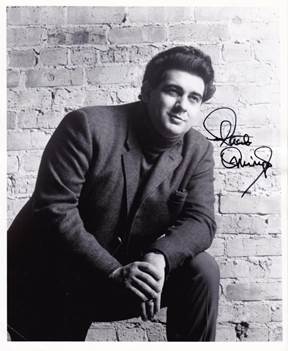

Rudel is very proud of City Opera’s engagement of a very young Placido Domingo, whose legendary career is now known to everyone. He sang at City Opera, sporadically, for nine seasons; full time at first, but less frequently, more as a guest, as his international career gained momentum. Most opera aficionados are aware of the list of great singers who started their careers at City Opera. One story I did not know was that in 1957 the planned staging of Macbeth was to feature Cornell MacNeil in the title role and Irene Jordan as his scheming wife, but this was at the time when he was getting good offers from the top European theatres. MacNeil was relieved of his commitment and William Chapman took his place. Rudel proudly recalls that Leonard Warren observed one of the performances and so liked what was then a rare Verdi opera (in the United States, at least) that he asked the Met to plan a production for him. Of course when the Met finally planned to present Macbeth, Maria Meneghini Callas was as much of the impetus as was Warren.

As New York City Opera had at best two ten-week seasons a year, there was time for Rudel to accept other “blue chip” assignments. He ran the prestigious Caramoor Festival outside New York City for fourteen years, graced the Cincinnati May Festival, and was a major player in crafting the Washington Opera’s initial seasons at the Kennedy Center in Washington, which also made him a “natural” nomination for the early implementation of the major Wolf Trap Festival in the Virginia suburbs of Washington. There are elements of the New York City Opera “look” in all these assignments. I personally heard the wonderful performance of Handel’s Ariodante with Sills and Tatiana Troyanos in the opening week of the Kennedy Center (The actual opening event was the world premiere of Leonard Bernstein’s controversial Mass). Sills performed her Traviata and Roberto Devereux at Wolf Trap, both preserved on DVD with basically New York City Opera settings and casts.

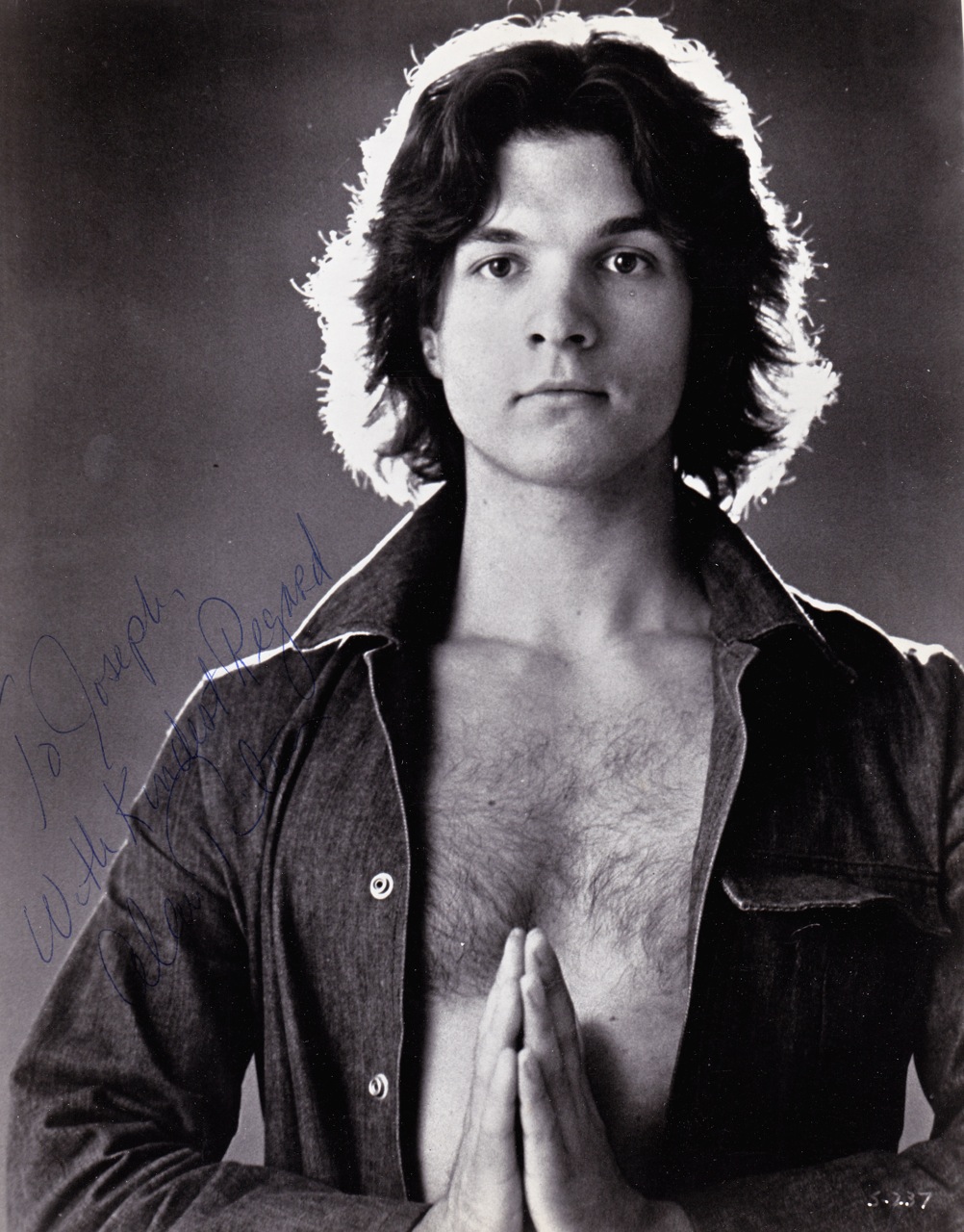

(Alan Titus in Bernstein's Mass)

(Alan Titus in Bernstein's Mass)

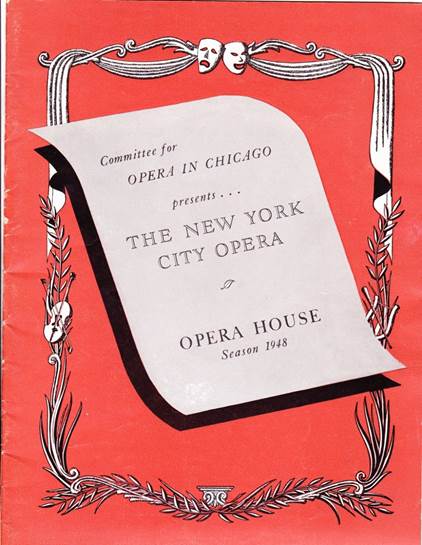

There are occasional references to the New York City Opera tours, not chronicled in either the great Sokol book or Rudel’s memoir, although Rudel does mention them. For the years 1948-1952, if I am not mistaken, the New York City Opera with its very best casts played at the Chicago Civic Opera House in the seasons that Chicago did not have its own resident company. These best casts were helped along with some guest artists. In Detroit, Jussi Bjorling, Eileen Farrell, Ferruccio Tagliavini and Hilde Gueden, for example, helped give the City Opera casts extra and international distinction. And Rudel took his company to Los Angeles in its great days (basically the Sills’ years) for seasons heavily subsidized by Lloyd Rigler and his partner Lawrence Deutsch, two very dependable patrons of NYCO. I believe Birgit Nilsson helped out in Los Angeles one opening night when Sills was indisposed. Neither the Sokol book nor Rudel’s memoir give many specifics about the frequent tours the NYCO gave in the Northeast. If I recall correctly, Opera News used to publish these tour itineraries. This is important to me, because I was visiting my hometown, Burlington Vermont in the late 1950’s, and the touring NYCO gave a performance of Fledermaus at the Municipal Auditorium, and it starred Beverly Sills, the first time I heard her, and I was mightily impressed.

Perhaps to inject a little spice and controversy into the memoir, Rudel tells of his awkward relationship with “the great Jon Vickers.” They had worked in Paris on the famous star-studded production of Monteverdi”s L’Incoronazione di Poppea with no major problems. In 1983, after Charles Mckerras pulled out of the project, Vickers asked Rudel to conduct his planned performances of Handel’s Samson in London, Chicago, and ultimately at the Met. Rudel planned to use some countertenors and conduct from the harpsichord, as he learned this was the original period practice from extensive research. Vickers told Rudel that there would be “none of that castrati stuff.” (Jeannie Williams in her Vickers biography quotes him as saying “I hate these sissified versions”) In London Vickers challenged Rudel’s so-called authentic period ideas. Vickers let it be known that learned his Handel style from none other than the great Sir Thomas Beecham. In Chicago Vickers humiliated Rudel in front of the orchestra and soloists shouting that he didn’t know what he was doing. Rudel marched into manager Ardis Krainik’s office and tendered his resignation, but Krainik diplomatically secured an apology from Vickers for his intemperate tirade. Rudel pulled back his resignation, but laments that only he heard the apology, not the orchestra or soloists.

Rudel in one of the final chapters gives “his” version of the transfer of the directorship of NYCO from himself to Sills. She had told him very early on in her great years (1965-1977) that she planned to stop singing when she turned 50, so that would be 1979. As early as 1977 she was sort of the co-director of the company involved with long-range planning, and this, of course, generated a lot of press notice. The press was looking for nuances that would indicate tensions in the executive suite. Rudel throughout the book fondly reminisces about the earlier years at City Opera when Morton Baum was the “heavyweight” on the Board of Directors and was someone Rudel could go to for guidance and support. After Baum died, and with the growth of the City Opera and Ballet and the other constituents, the Board of Directors now included additional prominent leaders from the worlds of finance and politics. A new “millionaire/billionaire” (in quotes as he seemed to come out of nowhere) John Samuels III from Texas assumed the leadership role after having initially made a very substantial financial contribution, and he had grandiose plans for reorganization of the City Center and its mission. The result was that the press portrayed a situation tantamount to a palace coup, with Sills throwing Rudel under the bus. Thinking about the details Rudel provides, one can only come to the conclusion that you cannot create something as nebulous as a co-directorship without each director’s roles spelled out in writing, sort of a binding contract. Grandiose, undefined roles can only lead to misunderstandings. Sills would tell favored members of the press that she had no idea how dire was the company’s financial situation. Rudel finds this unbelievable. He states that only three people knew of the internal tensions, Sills, himself and Samuels and they had agreed not to “leak” to the press. He assumes the incendiary article by Bill Zackaraisen in the Daily News and on the front page of the New York Times portraying Rudel’s dismissal and Sills’s elevation could only have come from one source. The result was that Rudel’s wife Rita, who up to that time was very close to Sills, never spoke to her again.

(Carreras-Ramey-Diana Soviero-Irene Jordan- Brenda Lewis)

This book is a fascinating bit of operatic history, as much for the opera politics discussed as for Rudel’s personal story. As Rudel’s career had some personal resonance for myself I found it hard to put the book down. Much of what is discussed in the book is fairly well known, or versions of it. Still, in this era when fewer and fewer books and memoirs are being published in hard-cover book form, I can recommend this work and hope it will find an audience.