152 pages. Leonardo Arte 2OOO.

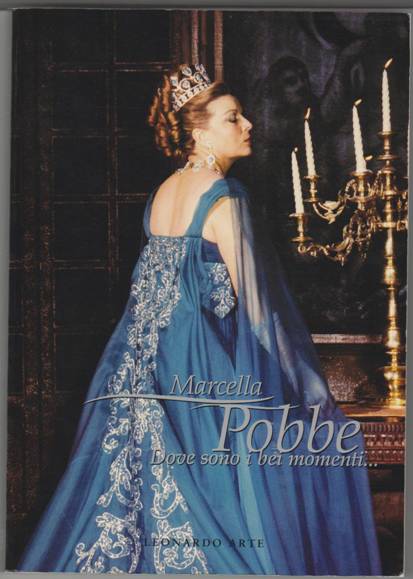

MARCELLA POBBE: Dove sono i bei momenti.

152 pages. Leonardo Arte 2OOO.

How vain can a singer still be a quarter of a century after her last operatic performance ? Very vain. You won't find Pobbe's birthday in this book, not in her reminiscences and not in a biographical note by Paolo Padoan. Kutsch-Riemens opts for the 13th of July 1921 which makes her eighty and moreover exactly three years older than Carlo Bergonzi, born on the same day. Kutsch-Riemens is probably right as the lady admits to a marriage that was already broken ( a terrible thing for an Italian woman in those days) before she made her début in 1949.

That's one of the frustrating things in these memories written three years before her death. As some aspects of her life are widely known the lady says A without however adding B. We may not know the name of that husband, nor the name of the man she loved for most of her life (probably a married man who in the true Mediterranean tradition liked to have a 'second office' without divorcing his first one). Her well-known affair with Nicolai Gedda she describes in the following words:"I was happy because during the tour (of the Met in 1958) Nicolai Gedda had become near to me so that we had a fine friendly rapport that contributed in making our Faust realistically on the interpretative level". This literal translation also makes it clear that the language used by Pobbe is somewhat old-fashioned and not very direct.

Do not expect therefore a completely honest, straight and frank discussion of her career or even her voice. Pobbe mostly goes from triumph to triumph. Once more it needs reading between the lines, listening to her records, studying her chronology to find the full truth. The voice on record is a nice even lyric one that projected well, though not very personal with a somewhat white colour: not an overwhelming instrument though it was even from top to bottom. But probably more of a lirico leggiero than a real colour rich lyric soprano. One day while rummaging through my collection I hit upon a cassette that said: Concert Ernesto Veronelli and Marcella Pobbe; given at Flemish Public Radio and Television where I worked myself as a producer. It slowly dawned upon me I had seen and heard the lady live in 1972 and still only remembered a somewhat faded beauty but the voice definitely made no impression (good or bad). At the time I probably thought: just an acceptable house soprano.

The chronology (well done by Paolo Padoan) tells it all. Even though in post-war Italy there was a burst of operatic activity not-so-young Pobbe' first real complete operatic season is 1954, five years after her operatic début. In the meantime she was rather busy with those fine scores real operatic diva's cannot be lured into so that lesser-endowed mortals carve out a career with that kind of music. Pobbe did a lot of lieder-concerts, sang Milhaud and Honegger. Even when her career took flight she sang the roles which Callas, Tebaldi and Stella graciously or forcefully declined . Her Scala début was once again in a Milhaud piece (David) followed by Il Franco Cacciatore (Der Freischütz). Later on, in her Russian period as she herself calls it, she sang a lot of lesser known Mussorgski and Tsjaikowski-roles. An interesting route but Pobbe never admits that she was cast in these roles 'faute de mieux", because with the exception of a Tebaldi Onegin no real star could be found to do them. Of course she gradually got Italian roles as well, a lot as a partner of Mario Del Monaco's Otello. But even here she doesn't tell us one of the main reasons for her engagements, though it is clear for all to see in her best known Italian role: Mascagni's Isabeau. She was a tall strikingly beautiful lady and therefore had 'le physique du role'

Nevertheless she is too astute an observer (and a music critic after her operatic career) not to know where her real strength was. She regrets that she arrived at an audition with Karajan somewhat tired and asked for a later hearing that never came into being. Otherwise she rightly concludes that she could have been a very fine Mozart soprano for which her voice and looks would have been outstanding. (her first Cetra-recording were a few Mozart-aria's).

So she sang a lot of Italian opera as well for which the voice was not really suited; Tosca, Ballo, Fedora, Andrea Chénier. She made it to the Met for one season only. In that ignoble documentary "Stephan and the prima-donna's", Zucker had conversations with interesting ladies as Barbieri, Cerquetti, Gavazzi, Gencer and Pobbe wasting everybody's time by being only interested in the use of chest voice. He mortally insulted Pobbe by asking again and again after her affair with Gedda as the only topic worthy of conversation. Zucker still wants us to believe that while contacting her she had promised to tell all and then refused when the camera was on. But the way this cheat slyly tells his team (and us) of her lover’s quarrel before the interview belies his words. Anyway he could still have asked her a lot of questions as her career unfolded during the most interesting post war years. Zucker says that the quarrel with Gedda was the reason for her not being re-engaged as she broke her contract. That is probably true and Pobbe only tells us that she didn't need to come back at the Met. Full stop. But Rudolf Bing sometimes forgave queerer behaviour from singers when he really needed them. With Dorothy Kirsten and Eleanor Steber on the pay-roll, both superior in voice and resembling in looks to Pobbe , Bing really didn't need the Italian soprano.

Pobbe has some interesting things to say on the end of her career when she lost her voice after some Aida's in Caracalla in 1975 (a role for which she was singularly unsuited). She describes the fear and hopes of an elder singer who realizes the end is near, stresses the consequences of menopause for a female singer. Her memory is not well served by the re-issue of her Cetra-recitals on Warner. The LP’s gave us an honest picture but on Warner one has the definitive impression the technicians used the knobs to give more body to the voice. There is a sad post scriptum to this book. She started writing reviews for Il Gazzettino (a local newspaper for the region of Vicenza). A colleague at Italy’s most important quality paper says they were intensely knowledgable as she was a lady with a broad cultural background. Some of her interviews with conductors were published in a book. But as is clear from this book she was quite lonely and forgotten at the end of her life. When she died from heart failure in her Milan apartment in June 2003 nobody noticed it until several days later. Though not completely satisfactory, it nevertheless remains a relief to read about the career of somebody else than Madame Callas. Moreover biographies of second- and third-rank singers are always more interesting for readers wanting to know more about the real jungle the operatic world often is

Jan Neckers