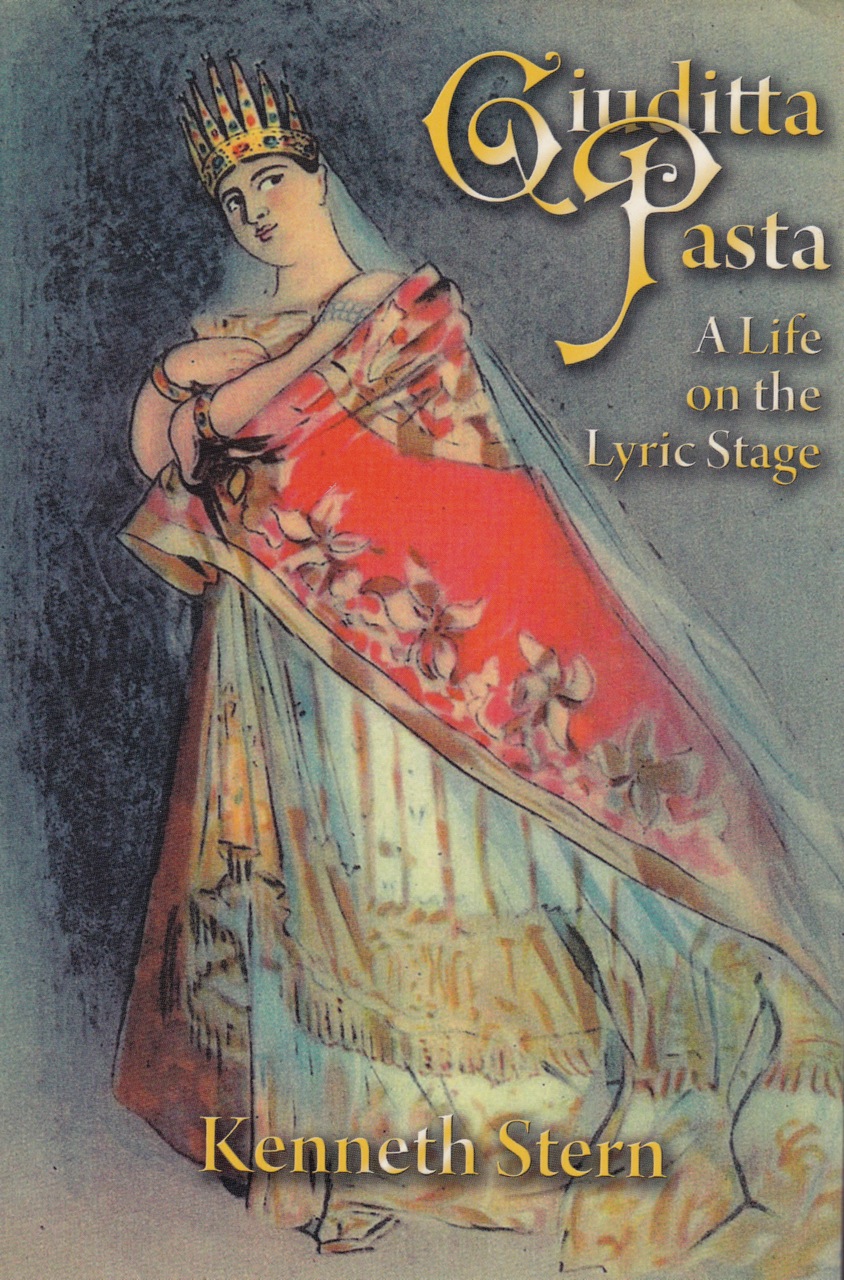

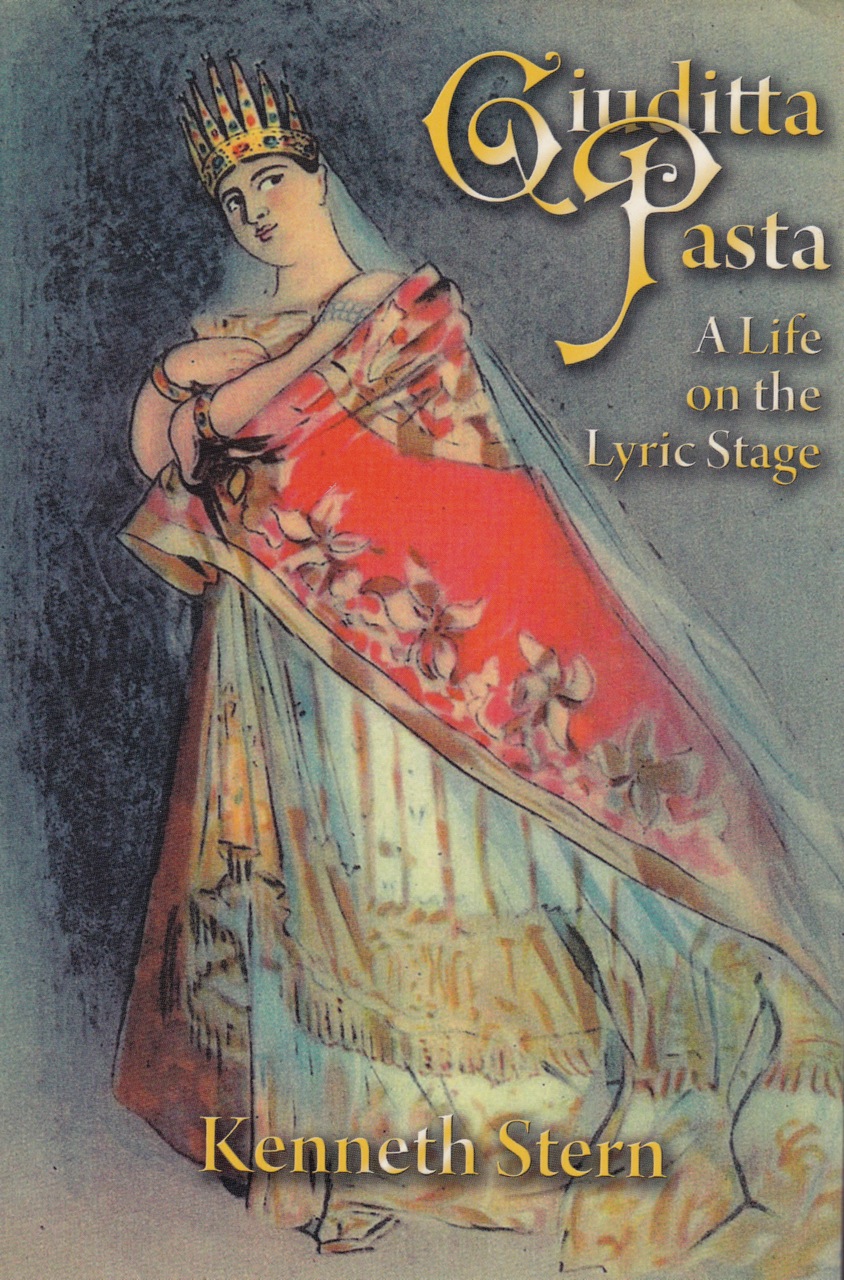

(as Norma)

(as Norma)GIUDITTA PASTA: A Life on the Lyric Stage (illustrations of the review, courtesy Charles Mintzer)

Kenneth Stern, self published

USA$49.95; limited edition

Vendor: rogergross@earthlink.com

(as Norma)

(as Norma)

The great British actress and writer Fanny Kemble said of Giuditta Pasta: “Madame Catalani is the first of the queens on song that I have seen ascend the throne of popular favour, in the course of sixty years, and pretty little Adelina Patti the last; I have heard all that reigned between the two, and above them all, Pasta appears to me pre-eminent for musical and dramatic genius --- alone and unapproached --- the muse of tragic song.” This quote is the blurb on the book’s dust jacket to provoke the reader’s interest.

This book is a serious study, in English, of one of the all-time great names of Nineteenth Century opera, the creator of Norma, among the twenty roles specifically written for her. There have been other books and monographs in Italian on this legendary artist, and Stern has used these studies upon which to build his own considerable original research. He has spent years studying everything that was written about Pasta in her own time, and these letters and reviews form the backbone of his study. Stern in the acknowledgements thanks one of Pasta’s descendents for allowing him access to her villa where he was able to review more of her letters and memorabilia. He was fortunate to have access to over 500 Pasta letters and documents held at New York Public Library’s Performing Arts Division. Stern has in the past published three scholarly articles on Pasta printed in Opera News.

There are so many things we want to know about this extraordinary artist, especially we want to construct in our own minds what her voice and artistry were probably like, a voice that inspired Bellini to pen both Sonnambula and Norma for her unique talents. We tend to think that the demands of these roles require polar opposite voices in terms of color and power. But in the early nineteenth century many of the vocal categories that we now use to describe voices were not in use. Very often a soprano was just that, a female singer; for example Pasta sang both the alto Cenerentola and lyric Amina and Marietta Alboni, whom we believe was a great alto, sang Leonora in La favorita and also Amina. All singers, men and women, were expected to have decent coloratura techniques; there was no such thing at that time as a “coloratura soprano.” It is significant that Bellini, Rossini, and Donizetti all adored her. A recurring statement in the many reviews is great praise for her singing of rapid scales and her trills (called “shakes” in England).

Stern, very early in his book, challenges the long-held assumption that Pasta was Jewish or of Jewish origin. It seems that an early nineteenth-century lexicon of musician’s categorized her as Jewish, probably based on the fact that her mother’s first name was Rachele, and Giuditta (Judith) was an Old Testament name. Also, the family name Negri (meaning “Black” in English and “Schwartz” in German, and often a Jewish family name) may have led the lexicographer to this erroneous assumption. Stern maintains there is no evidence that the family practiced any religion other than Roman Catholicism, nor is there evidence that Pasta had Jewish ancestors who had converted. Stern uses this as a case-study of how an innocent, but unfounded, entry in a widely-used dictionary took on a life of its own, repeated over almost two hundred years, to the extent that it became an accepted truth ever since then. There is an interesting “back story” as to how her possible Jewish identity came to the attention of the erring lexicographer.

(as Anna Bolena)

(as Anna Bolena)

As Anna Bolena is very much in the news these days, it is interesting to read of Pasta’s original performances, and it also served years later as Pasta’s farewell to the stage. At the premiere the new opera elicited mixed reviews, but all admired the final mad scene, and Pasta’s performance was considered a masterpiece; her ascending trills thrilling the most discerning critics. Long after she had stopped her main career, she visited England, the scene of many of her triumphs, and participated in a gala performance, singing the Giovanna Seymour duet and the final mad scene. This is the performance that has achieved fame as the critic and chronicler of that period, Henry Chorley, wrote memorably about this event in his historical overview of the great singers he had heard. It seems that Pasta’s voice at this time was in shambles and she was only able to give a sketch, at best, of her scenes. At the time of the event Chorley wrote in The Athenaeum “But all defects admitted, sufficient grandeur of style, breadth of phrasing, decision of accent, and dignity and brilliance of execution combined, remained to justify the utmost warmth with which we should recommend this distinguished woman as a model to all artists of the younger world.” It was at this performance that the young Pauline Viardot commented, “you are right! It is like the Cenacolo of Da Vinci (The Last Supper) – a wreck of a picture, but the picture is the greatest picture in the world.”

Stern has developed a chronology format that is very informative yet takes only a few pages. He lists in chronological order Pasta’s first assumption of her sixty-three roles. After each entry he then lists her history of these roles; for example, after the first Scala performance of Norma, its premiere) he lists all the cities, by year, in which she sang the role, the number of times, for example in London and Paris, 108 times in total for the complete opera and 7 times Act II only. In the body of the text you will often find the names of her cast partners. He also lists the twenty roles that were created specifically for her, and the six existing roles that composers re-adapted for her. He lists, by year, the several hundred recitals she gave, mostly in homes of prominent members of society. By my count Pasta sang 1,240 operatic performances and 860 recitals/concerts; these numbers alone place her career on the highest plane.

This 584 page book (with a very good index) is copiously illustrated with lithographs as Pasta’s life and career predate photography. Stern draws a loving portrait of a singer who was the last word in professionalism and a considerate diva, one who got along well with composers and colleagues. Stern has stitched together a compelling narrative using period reviews and appraisals as well as liberal quotations from her revealing letters. Recommended.

Charles Mintzer