By Charles Mintzer

Miguel González Escobar: PANORAMA ILLUSTRADO DE LA ÓPERA: Ediciones Amberley, Madrid, 2009

By Charles Mintzer

This 159 page-book is an absolute delight, especially for collectors of photos of opera singers, past and present, most of whom were legends in their time. Seňor González Escobar should be proud of the collection he has assembled of “choice” images. It is an international collection, but with a Spanish flavor.

As a collector I experienced the emotions of pride and envy: “Where on earth did he find that image?,” “I wish I had that autographed photo myself, I suspect it is very rare,” “Wow, this guy had his own photo taken with Callas!” and my collector juices flow and put a smile on my face. The book is organized along general chronological lines, but not strictly. It contains wonderful examples of late nineteenth century images that give way to rarely seen photos from the early twentieth century. A Luisa Tetrazzini signed in Madrid in 1896 took my breath away as she is so young and we know of the greatness yet awaiting her. The great names from the last forty years often are images taken by the author himself backstage with the likes of Callas, Caballé, de los Angeles, and Pavarotti. There are never before seen images of Leontyne Price, Pilar Lorengar, James McCracken, and Mirella Freni.

The book is obviously more of a personal statement than the “panorama” suggested by the title. I view it more as highlights from the author’s considerable collection that he wants to share. It does not aim to be a comprehensive survey of the most important names in operatic history; how could a slender 159-page (with 168 images) photo book accomplish that? From the biographical information on the back cover it is clear that the author does not view himself as either a music critic or musicologist.

James Camner’s photo books, now hard to find, The Great Opera Stars in Historic Photographs and Stars of the Opera in Photographs (1950-1985) are broader surveys, and they cover a similar period from the perspective of an American memorabilia dealer, somewhat Metropolitan Opera or American-centric. However, González Escobar’s book of singers, conductors, and a few composers needs no apologies. For the historic singers of Otello we do not get Tamagno, Del Monaco or Vinay, but we do get Antonio Paoli, Julián Biel, Giovanni Zenatello, Giovanni Martinelli, Carlos Maria Guichandut, and James McCracken, none in Otello costume.

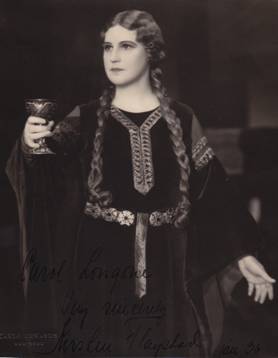

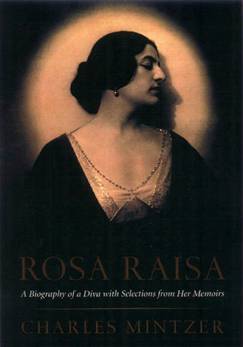

If the book is light on the French, American, German, and Russian schools of singing, I must assume that this is more a product of space considerations and the author’s understandable frame of reference than a deliberate slight. While there is no Beverly Sills or Eileen Farrell, there is a very rare Hollywood Grace Moore, Geraldine Farrar, and Marian Anderson. No Ninon Vallin or Lily Pons, but two superb Genevieve Vix’s (admittedly very popular in Madrid, not only for vocal reasons). No Antonina Nezhdanova or Medea Mei-Figner, but a very beautiful Maria Kuznetsova. The German school is very lightly represented, though there is an 1899 Ernestine Schumann-Heink, a very beautiful Selma Kurz, Walter Kirchoff (big career in Spain), Richard Tauber, Leo Slezak, Lotte Lehmann, and Maria Jeritza. No Rosa Ponselle, but a stunning Rosa Raisa.

You start to realize that González Escobar in this beautiful book is highlighting photos that mean much to him in his autograph-collecting travels. Most of the images are either extremely rare or are superb examples of the genre. A 1901 Arturo Toscanini signed in Buenos Aires, a Mishkin of New York of a demented Miguel Fleta as Don José, a Camuzzi of Milan of Maria Caniglia with a long dedication to Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, and a very rare image of Avelina Carrera, the first Maddalena in Andrea Chenier. Gonzalez Escobar is meticulous in identifying photographers and dates, as well as providing in Spanish, of course, brief summaries as to why a singer, conductor, or composer is important or important enough to justify inclusion. As we move into the mid-1960s with many of his own photos, he gives both the location and the date when the image was taken.

As a fellow photograph/autograph collector I can especially appreciate the scope and detail of this book and González Escobar’s wonderful collection. The book is not geared to specialists, but more to individuals who like to casually turn pages and see an array of superior examples of artists who have placed their stamp on opera history. As much of this collection was formed in Spain, there are several images that are not generally known outside that country. Some of these Spanish singers were zarzuela artists, including the mother of Plácido Domingo, Pepita Embil.

This inexpensive (19 Eur), reasonably-well printed, and indexed book is an attractive addition to one’s library.

Some Random Notes on Opera Photography and Autograph Collecting

I have been casually collecting operatic photos and autographs for much of my adult life and seriously collecting for the last twenty-five years. Almost fifty years ago I was given by Charlotte Bernhardt, a refugee woman with whom I worked in government service, a major collection formed by her husband, the late Heinz Bernhardt, of mostly autographed sepia postcards of opera singers who performed in Berlin. Herr Bernhardt kept a meticulous diary of all the opera, theater, and concert performances he attended, with casts listed in a systematic order (conductor, soprano, mezzo, tenor, baritone, bass). The postcard collection matched his activities; for a few years in the Twenties and early Thirties he attended as many as 300 performances a year. Remember, there were three functioning opera houses in Berlin: the State, the City, and the Kroll Operas. After the Nazis took power, his attendance at the main opera houses considerably diminished. He and his wife did attend many concerts and operatic performances at the Kulturbund, the segregated organization set up for Jewish artists and audiences, and these performances are entered in his diary. He and his wife migrated to the United States in 1938.

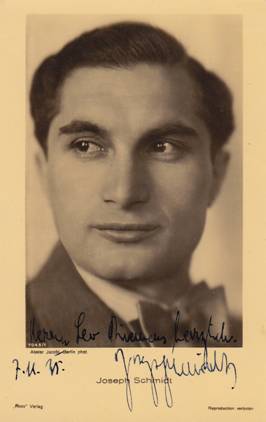

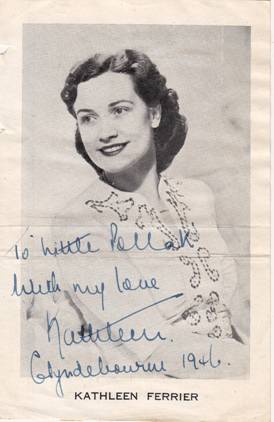

(two examples of the Bernhardt coll.)

(two examples of the Bernhardt coll.)

At the time Mrs. Bernhardt gave me the collection (she had had a difficult time interesting either individual opera lovers or memorabilia dealers in it), I didn’t take its comprehensive nature seriously and gave away many of the signed sepia postcards to friends who liked certain singers from that period. Had I had kept that collection intact I would have had the foundation of a world-class collection, trading the lesser or duplicated items for better or rarer items. Only around 1985 did I commit to forming a comprehensive collection; my goal was to have representative photos or even better, autographed photos, of most of the major twentieth-century singers, and even going further back for some of the top names of the mid-to late-nineteenth century, and letters where photographs were not possible. As an American, I had as reference points the artists who sang at the Metropolitan, Hammerstein’s Manhattan and the Chicago Opera. This orientation did not mean I was without knowledge of operatic currents and history of performance in Italy, France, Germany, Belgium, England, Spain, or Russia. As one can see from my collecting ambitions, I had set upon a very large project. In the twenty-five years I have been an active collector, many of my goals have been met, but truth-to-tell, there are some gaps in my collection that I am still trying to fill. And I am always eager to upgrade some artists with better or rarer images.

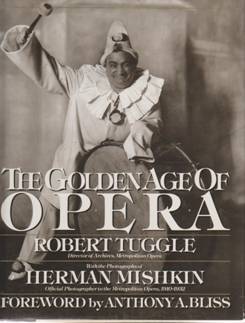

In 1978 I had the good fortune to meet Robert Tuggle, who a few years later became the archivist of the Metropolitan Opera. Bob at that time was working on his book The Golden Age of Opera, showcasing the images of Met photographer Herman Mishkin. I learned a lot of opera history and how to look at operatic images from this experience. Mishkin’s photographs have a certain feel, and I can almost always identify his photos, even if his “Mishkin, New York” is not printed on the lower part of the photo. Prior to Mishkin, in New York, there were primarily Aimé Dupont, Mora, Sarony, and Falk, who photographed the great opera stars when they were in New York. I had a particular interest in the Chicago Opera, which can be inferred from my biography of the great Rosa Raisa. Therefore I developed the ability, as with Mishkin, to easily identify Matzene, Moffett, Daguerre, Atwell, DeGueldre, and Seymour photos of the singers of that operatic organization.

(José Mojica by De Gueldre and Dal Monte by Moffett)

In time I became familiar with Nadar, Reutlinger, Harcourt, Bert, and Benque in Paris; Ermini, Varischi & Artico, Castagneri, Camuzzi, Villani, Luxardo, and Piccagliani in Italy; Setzer, Fayer, and Willinger in Vienna; Sudak in Buenos Aires; Dover Street Studio in London; several photographers in Spain, and Fischer of Moscow and Bergamasco of Saint Petersburg in pre-Soviet Russia.

Each photographer has a unique fingerprint, or DNA if you will, a look and feel that is unique and immediately recognizable. Although I have dwelt on the photographers of the first half of the twentieth-century, their successors, now working in color, also have some (but less individuality). Most color photography is of action shots, and there are fewer portraits. I have to admit that color photography does not move me emotionally as does the black-and-white (often printed in sepia) photography of an earlier era.

I embarked on an organized quest to secure signed photos of the opera stars still performing and also those who had retired and were still willing to sign. It was still possible twenty-five years ago to acquire unsigned photos from artist’s managers or even to find stashes of photos in used book and second-hand stores. I would try to find viable addresses of the retired artists, send them the photos with an appropriate cover letter, and a stamped self-addressed envelope for the return. This is not really much of an option today because unsigned quality photos have become very expensive, and the cost of postage (sending and return) is now relatively prohibitive.

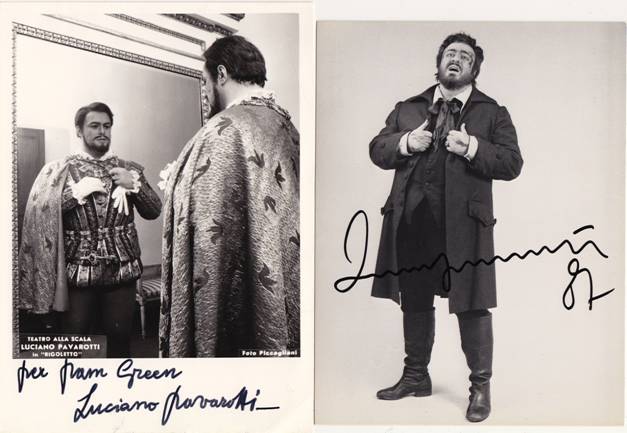

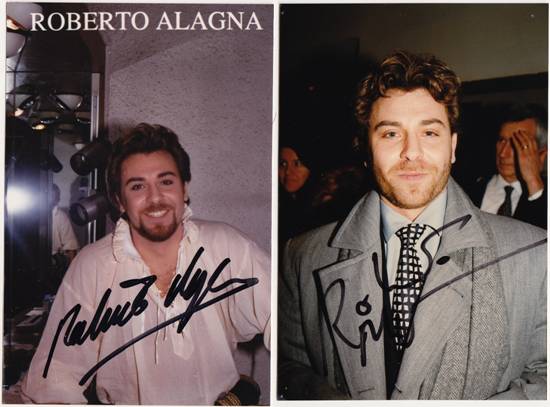

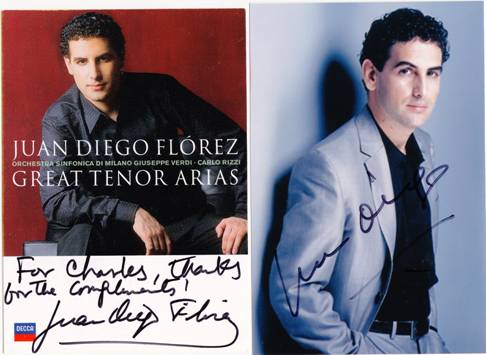

Some general principles: An original photograph with the photographer’s name handwritten in the lower corner or stamped on the back or embossed on the photo is obviously from a collecting standpoint more desirable than a copy. Most autographed photos on the market tend to be copies, some of better quality than others. A most desirable autographed photo is one of the artist at the peak of their powers, or very early in his or her career, one where the signature is clear (for example, Luciano Pavarotti’s after the 1970s are rarely more than a wavy scrawl; before that you could actually read his name). I notice now that Alagna signs his photos “Roberto” only and Flórez “Juan Diego.” A photograph inscribed to a famous person or someone in the profession, or one rich in associations is very desirable, like González Escobar’s photo of Caniglia dedicated to Lauri-Volpi.

(LP 1971-1987)

(LP 1971-1987)

Of modern photos, one signed in a fine (non-thick) felt-tipped pen or ink rather than gold or silver, for some reason favored by many artists even though these inks often flake or deteriorate, is desirable. Ball-point ink is a real problem; this became very popular after World War II and half a century later many photos have lost the ink and only the impression remains. When I had the pleasure in 1985 of interviewing Dame Eva Turner (born 1892) about her association with the Chicago Opera for my Rosa Raisa project, I brought with me to London a set of rare photos that a collector friend of mine had printed for this encounter. Dame Eva signed them with dispatch, but she put her index finger on her tongue and rubbed the photos, which were not glossies, and signed them with a ball-point pen. I think she did this out of habit to create a rougher surface that would absorb the ink.

If the photo is not a portrait, but in costume, it should preferably be in a role in which the artist has some special identification or critical success. Photos of more than one artist, where both have signed near their image on the photo, are often desirable, but often not easy to obtain. Since sending photos to artists for signing is an unsolicited act, the artist receiving the photo(s) is under no obligation to return them, but almost all artists are happy to cooperate. Some artists insist on dating their signatures or putting the name of the sender on the autograph, making it so personal that it is less desirable to trade later on; this is important when one is making a comprehensive collection as one often trades duplicates or extra photos to obtain a photo of another artist on his want-list. Some artists will keep a rare photo that they don’t own and substitute what they think is an equally good photo; this is rarely the case. This happened to me with both Gerard Souzay and Renata Tebaldi.

To the uninitiated the range of prices for autographed photos of a particular artist can sometimes seem baffling, but the range of prices is logical. Take Mattia Battistini, for instance. An ordinary signed postcard of a common image can fetch as little as $125.00 whereas a cabinet photograph, in good condition, with a spectacular image and a great signature and dedication will often bring upward of $675.00. A Maria Callas (not Meneghini Callas) 4x6 inch photo dated in the 1970s will go for about $850.00-$1,000. A large photo, in great condition, in a role such as Norma with a large “Maria Meneghini Callas” might bring over $2,500.00. I have seen Anna Netrebko 4x6 color photos go for $25.00, but very glamorous photos sometimes go in the $100.00 range. If it is a double photo with Rolando Villazon, signed by both, and of good quality, it might fetch over $100.00.

Autographs sometimes even lead us to “psychoanalyze” artists; why did Kirsten Flagstad almost always sign on the dark part of the photo? Was this because of an innate deference and not wishing to promote herself? A charming anecdote is that a person who wrote her a fan letter and by custom received an autographed photo in thanks later told Flagstad that the autographed photo was not genuine as the writing on the envelope was the same as that on the photo. Flagstad was known for personally addressing her envelopes. Does Victoria de los Angeles’s very florid and ornate signature, one of the most desired and beautifully-crafted, indicate anything about her true personality? Does Erna Berger’s minuscule signature or Joan Sutherland’s bold writing tell us anything?

Each individual has to figure out what he wants to achieve and devise his own strategy in building his collection. There are dealers who specialize in performing-arts autographed photos, and there are online resources to buy either by retail or auction. These dealers can be found by creative “googling.” You will learn early on that Maria Callas (even better Maria Meneghini Callas), Jussi Björling, Fritz Wunderlich, Conchita Supervia, Kathleen Ferrier, Joseph Schmidt, and Enrico Caruso are among the most valuable, and therefore expensive, autographs. What do these seven have in common? Undeniable greatness and death at a relatively young age. Callas and Caruso were very generous and signed tons of photos during their short lifetime; Björling signed much less due to his health problems, Wunderlich on the verge of one of the great international careers died in an accident, Supervia died at age 40 in childbirth, Ferrier was taken from us by cancer, and the young Schmidt was a World War II victim. However, as more people still want their autographs than there are supplies, this keeps the prices high.

This phenomenon I am told is true in all areas of collecting: Marilyn Monroe, Edith Piaf, John Lennon, James Dean, Elvis Presley are a few examples from the entertainment world; you can only imagine the value of the assassinated presidents, John Kennedy or Abraham Lincoln. When one is buying autographed photographs from a dealer, and one is not certain if the dealer can be trusted, and if price and quality are issues, it is wise to take note if the dealer is a member of a professional autograph association that “vouches” for the integrity of the dealer. The peer pressure of these organizations does keep the autograph seller community basically honest. Having said that, one must always be aware that one is delving in an area where one’s own knowledge must come into play in judging the real value of what is being marketed.

There can be no question that the internet has changed collecting opera autographs and photos as it has changed all types of collecting. Retail dealers have websites where their offerings can be attractively digitalized with enough space to describe the significance of the photos. And, of course, eBay has changed the whole landscape of all types of collecting. My observation of the eBay phenomenon is that rare, high quality and desirable offerings, properly described and “key-worded,” often realize a very fair and sometimes an astounding price. Mid-level and lower-end offerings often go for very little or not even make the starting price; I think this has more to do with basic economics. I think some dealers have figured out how to work the “net” and are doing very well. Unknowledgeable dealers get rude awakenings when they list offerings at high starting prices and get no takers. For example, I have seen signed Caruso photos that started at US$499.00 not enticing any bidders, and this for a photo that I estimate should retail for $750.00 to 1,000.00. I think the $499.00 starting price is a “turn-off” to many prospective buyers. If the dealer had started the bidding at $99.00, for instance, and two or three prospective buyers had marked the item as one of great interest, it might in the end have achieved the fair retail price. And dealers of very rare material can put a “reserve” on their offerings if they fear the item will not achieve a satisfactory price.

(Art Nouveau postcard, Caruso Buenos Aires, 1903,pre-Met debut)

Many of us are interested in various developments of society and demographic breakdowns. It is my observation that there are fewer young people collecting opera-related photos, autographs, records, books and ephemera, or for that matter attending operas, even in HD, concerts, and theater, at least in the United States. The energy of young people seems to be directed elsewhere. That does not mean there are no younger collectors, but only that there are fewer than there were at one time. The AIDS crisis carried away some significant collectors, and brought some fine collections to the market.

I have often been asked about forgeries. There obviously must be some inauthentic signatures floating around, but in the opera world this is less common than in the more popular entertainments such as the cinema. Opera singers have always been asked for their autographs, either after a performance backstage or by letter, but never on the scale of popular-music artists, screen stars, political figures, or sports icons. If there are forgeries they would be of artists who are rare; what would be the point of forging a signature that is easily available? However, busy artists like busy executives often have secretaries or assistants who are authorized to sign their names to correspondence. One can only be certain 99% of the time that what one has in his collection is genuine, not a “secretarial” signature.

One should also be aware of the difference between a true signature and a mere identification. Many older cabinet and carte-de-visite photos have the name of the artist nicely written in script either on the front of the photo below the picture near the photographer logo or on the verso, where normally there would be an artist signature; often these are merely identifications. Rarely does the handwriting of the artist look anything like that of the identifier. These are not forgeries, but on occasion a dealer will pass off an identification as the real signature. Over the years many artists got tired of writing their name and had photos printed up with their signature already on them. Printed signatures of this type are sometimes passed off as real signatures and one has to be ever alert to this. I have a Russian postcard with a printed signature of Mattia Battistini, but the inscription, in different ink, is clearly in his hand; I have several Battistini letters and postcards with which to compare his writing.

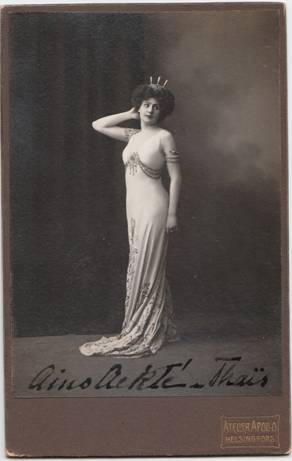

(Aino Ackté, an identification and the real signature)

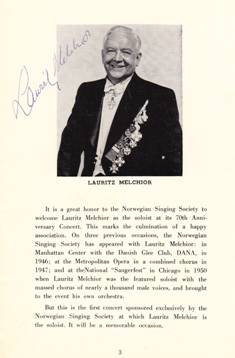

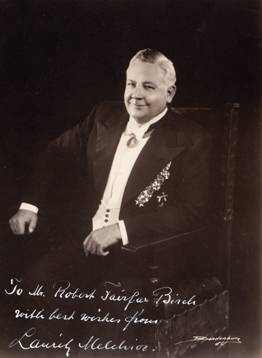

I was once told years ago that Lauritz Melchior’s wife Kleinchen signed and mailed out most of his autographs. However, in 1960 backstage at the Brooklyn Academy of Music where he participated in a fund-raising concert for a Scandinavian music society, he signed my program in my presence; we actually had a very pleasant conversation, albeit short. The signature matched up in every particular (flow, letter formation and break between the “i” and the “o” in Melchior) with the several Melchiors that I already owned. The question for me now is: did Kleinchen really master his signature or did Melchior copy Kleinchen’s good imitation of his? Is this art copying life or vice versa?

(his or Kleinchen’s writing?)

(his or Kleinchen’s writing?)

Collecting in any area cannot totally ignore the issue of potential monetary value even if that aspect is not even on the mind of the collector when in the act of collecting. Obviously, in all market situations, there are value fluctuations. Just as Callas has gone up in value, Renata Tebaldi has gone down. This has very little to do with artistic stature or star power. Callas died young, a cottage industry celebrating her greatness came into being with books and treatises, and a popular Broadway play, “Master Class,” was built around her persona; this drama introduced her to an additional segment of the public. Tebaldi lived to a good age, and was very generous in signing photos until her last days. Tebaldi autographs from the 1940s and 1950s will have more monetary value than the photos she signed in older age when she signed with a heavy flair pen. When I started collecting and becoming aware of the monetary side of collecting, good Claudia Muzio autographed photos were retailing for about US$600, and now the same photos will go for around $300.00-$400.00. People who owned Muzio photos when she was still a great and treasured name have died, their heirs sold their collections at a “high” time in the market, and now the new generation of collectors already have Muzio in their collection. It is possible that interest in her has somewhat declined. We all learn in many aspects of life that fame is ephemeral. A great name in 1910 may mean very little in 2010. Of course, old/antique “things” always are collectible on some level.

(signed in 1955 and 1995)

(signed in 1955 and 1995)

For many years during the height of communism in the former USSR, Russian autographs, pre and post revolution, were very rare in the West except for the likes of the legendary Fodor Chaliapin who only performed outside Russia after 1922. Lemeshev, Sobinoff, Obukhova, the Figners, and Ershov were well known in the West from their recordings but their autographs were virtually unknown. In the early 1990s with the barriers down, a flood of autographed material showed up in the West. At first these items brought very large prices, but with so many of them now on the market the prices had to come down. Pre-Soviet Chaliapin autographs, some of them amazing images, still bring good prices but perhaps not what they did many years ago.

I was asked by the editor of this webzine what were the rarest items (and by inference, the most expensive) in my collection. I have to think it is an 1825 affectionate letter of Maria Malibran to Giuditta Pasta in Paris, signed “Giulietta/Marietta Garcia” with a postscript signed by her mother Joaquina Garcia.”

(Charles Mintzer in front of Malibran’s tomb in Laken, summer 2009, photo taken by the editor)

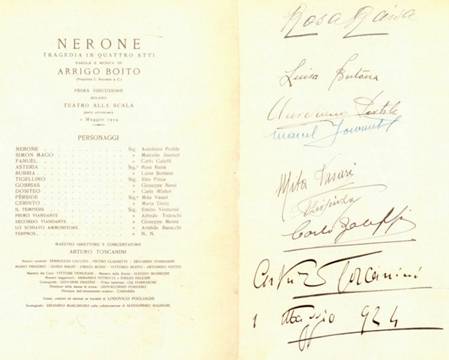

A close runner-up is the score of Boito’s Nerone signed the night the world premiere, 1 May 1924, with the signatures of Rosa Raisa, Luisa Bertana, Aureliano Pertile, Carlo Galeffi, Marcel Journet, Ezio Pinza, and conductor Arturo Toscanini. (This page from the score is pictured in my Rosa Raisa biography). Interestingly, a while later I bought a Puccini letter to his London friend and confidante Sybil Seligman, the day after, 2 May 1924: “The opera Nerone was a great success – fantastic representational sets, impossible in any other theatre – splendid! And the music? As far as I am concerned – and only I – give me any melody and I like it. But in my opinion it is a shortlived opera because it lacks a genial wise man. It’s a poor old man dressed well enough, so it’s a great bluff, but it is the setting and the advertising that have made it a success and it is totally ephemeral. So here are my honest impressions, which are those of the majority as well, even the journalists. When they speak to you face to face, they fake it, but when they write, it’s another story.” This is a 1924 version of “political correctness” as one did not lightly criticize Boito or Toscanini

I have a score signed by Puccini of “La Fanciulla del West” dedicated in London, 1911, to the great bass-baritone Vanni-Marcoux in recognition of his superb Scarpia which Puccini witnessed at Covent Garden. Tito Ricordi and Cleofonte Campanini also signed the score as well as Amadeo Bassi who sang Dick Johnson in London, and later Vanni-Marcoux had Caruso sign the cast page. Post World War II, when Vanni-Marcoux did some stage directing, the score has numerous markings in his hand re the acting.

People may wonder how I maintain my collection for safety? For preservation I keep all my autographed material in plastic or mylar protectors. This obviously doubles the space needed to house the material, but it is a necessary safeguard. I had an unfortunate water accident five years ago in my home, where if I had not had the material in such protectors, I may have lost a good part of it.

(then and now)

(then and now)

In my experience autograph and photograph collecting has enriched my love of opera; it has given me an additional window through which to view this incredible art form. Collecting photos and autographs as well as biographies, chronologies, opera house histories, and other operatic ephemera have made my retirement years especially meaningful. Moreover, this passion has given me the opportunity to meet very interesting people from all over the world, many of whom have become treasured friends. I enjoy sharing my photos and autographs, and the internet has been a good outlet for this impulse. Ultimately for me, opera photography records the range of feelings written on the human face, and the technology of the camera keeps me happily on this journey.