Paul Fryer

A Chronology of Opera Performances at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, 1860-1917

The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, New York, Queenston, Ontario and Lampeter, Wales

www.mellenpress.com

Review of Charles Mintzer

Professor Paul Fryer and his research team in Russia have made a substantial contribution to the library of opera-house chronologies with this definitive work. Imagine 1,200 pages chronicling fifty-seven years of complete daily listings of every opera performed in this legendary theatre, the site of so many important world premières of Russian operas. Painstaking work with archival records and contemporary newspapers has made this work reasonably accurate. The nights when opera was not presented, the famous Mariinsky ballet performed, but the ballet is not in the scope of this work; see title.

In the overall history of world opera there are many references to the rich operatic life of St. Petersburg up to the 1917 revolution, but this is often a reference to the great Italian (with some French and German) seasons with the world’s greatest singers, given in various theatres in that metropolis. The Mariinsky was the Imperial Theatre, supported by the Romanov Czars, and patronized by the nobility and the aristocracy, giving all operas in Russian with Russian singers. Of all the operatic activity in this great opera-loving city the Mariinsky was the only theatre that was a distinctive institution with its own identity, rich history and roster of singers (like the Metropolitan in New York or the Opéra in Paris, for instance); the other operatic activities were those of companies put together by enterprising impresarios, often with no season-to-season continuity. At the Russian-language Mariinsky on rare occasions artists such as Mattia Battistini, Giuseppe Anselmi, Nellie Melba, the de Reszke brothers gave guest performances in what had to be bilingual presentations, although the language issue is surprisingly not clarified. Perhaps Battistini sang his Eugene Onegins in Russian as he probably learned enough Russian during his appearances in the various Italian seasons.

Amplifying on the riches of operatic life in St. Petersburg, there were in addition to the Russian opera at the Mariinsky, various “private” opera companies and the glamorous Italian seasons, a significant second-tier level of opera given in various large venues (the Narodny Dom, for instance) often with very important singers, many of whom made treasured recordings. Russia has always produced a plethora of richly-endowed, well-trained operatic-quality singers. An example is baritone Oscar Isaievitch Kamionsky, dubbed the “Russian Battistini,” who was kept out of the imperial theatres due to his refusal to undergo baptism, a strict condition of employment, rarely waived. Alexander Mikailovich Davydov, nee Levinson, told aspiring baritone Sergei Levik that his chances of acceptance at the Mariinsky were nil as he was told that only he, Lev Mikailovich Sibiriyakov, nee Spivak and Nikolai Abramovich Rostovsky, nee Frumson, would be the last unbaptized Jews allowed to join the theatre. Professor Fryer’s new book is only about the Russian operatic crown jewel, the Mariinsky.

Speaking of Levik, his memoirs, “An Opera Singer’s Notes,” is perhaps the most frequently cited work by both modern Russian and Western writers covering the period 1900-1930. His observations and critiques have extra value as he was both a working singer as well as an astute observer of the St. Petersburg operatic scene. He describes the singers from all three operatic milieus (the Mariinsky, Italian companies and second-tier enterprises) with both technical and artistic insights. The book was translated into English in 1995, a project of Symposium Records, and is now hard to find. As one goes to Levik for appraisals of artists and an insider’s interpretation of their overall place in history, one now goes to Fryer for the actual hard data.

After the Bolshevik revolution the Mariinsky in 1919 became a “People’s” theatre, GATOB (State Academic Theatre Opera and Ballet) and in 1935 renamed the Kirov (after Sergey Kirov, the Communist party boss of Leningrad, murdered on 1 December, 1934). After the fall of communism in the 1990‘s the Kirov opera company regained its original name, Mariinsky. The Bolshoi theatre in Moscow, pre-1918, was also an imperial theatre, and has an almost equally impressive history. After 1918 and the shift of power from St Petersburg to Moscow, the Bolshoi in the Soviet period became that country’s preeminent opera and ballet theatre.

This is the only recent opera house chronology to use the William Seltsam method of listing; this refers to the compiler of the ground-breaking annals of the Metropolitan Opera published in 1947, supplemented in subsequent decades, and corrected, recompiled and updated in the centennial edition taking the company history through 1983. These hard-cover books have been supplanted by the free, online “interactive” Met database (www.metopera.org archives) which is able to give infinitely more information, updated daily, both performances and statistics, and is generally considered the outstanding easy-to-use “state of the art” opera company history, only made possible by the wonders of the internet and its almost unlimited potential.

In brief, for those not familiar with the conventions used to chronicle opera house histories, the Seltsam method lists chronologically, by season, the first performance that season of a certain opera, and that opera’s subsequent performances keyed into the date of the first performance, but with any changes in the cast noted (“same as...except”). This valuable format had been scrapped by many recent chronologers, especially those of European opera houses, in favor of shorter summary listings of the opera with either the first performance date, specific dates of the repeats, or more often just the number of times the opera was given that season, and the names of all the leading artists who sang in that opera during the season. This was less a problem for companies that gave clusters of performances (the “stagione” system) of one opera with few cast changes, but a nightmare for theatres like the Met that used the repertory system with lots of cast configurations. The problem with the summary system is that, other than the first performance of a run of an opera, one is never certain who sang together in the subsequent performances. The Mariinsky, like the Met, was a repertory house and only clustered a specific opera under very special circumstances. In my opinion, the best recent chronology, not using the Seltsam day-by-day method, is César Dillon’s (with co-author Juan Sala) El Teatro Musical en Buenos Aires: Volume II Teatro Coliseo 1907-1937/1961-1998.

Fryer’s books (two volumes) are hard to put down once one gets addicted to searching the performances of certain singers or operas of interest. As we all have different areas of curiosity there are infinite possibilities in these books to search. My own preference is to research in depth a particular singer’s career in a theatre with which that singer was widely associated. I chose for starters three headliners, the heldentenor Ivan Ershov, the very great Medea Mei Figner, and the charismatic lyric soprano Maria Kuznetsova; my next effort will be to research the important basso Fyodor Stravinsky, the father of Igor. In “stroke-tallying” their careers, one not only produces a summary of their total appearances by rôle, but one sees their domination of certain rôles, the ebbs and flows of their career, the casts they were in, and also the artists surrounding them and those with whom they shared rôles. For example, almost rarely does a tenor other than Ershov perform Tannhäuser, both Siegfrieds, Tristan, Samson and Raoul in Les Huguenots. But Ershov shares Lohengrin, Faust, Don José, the Mefistofele Faust, and many rôles in the Rimsky-Korsakoff operas. Medea Mei, married to Mariinsky star tenor Nikolai Figner in 1889, was an Italian-born mezzo-soprano, whose voice developed into a spinto soprano; she was a favorite of Tchaikovsky and created both his Iolanta and Queen of Spades (Lisa) at the Mariinsky. She also created several other Russian operas, and as her career went into a later dramatic-soprano phase she was a Walküre and Gõtterdämmerung Brünnhilde. A rôle taken on in mid-to-late-career was Carmen, and in her last years she was alternating Carmen with the Brünnhildes and Valentine in Les Huguenots, a very popular opera at the Mariinsky. I found Kuznetsova (a singer in many ways similar to Anna Netrebko in our time for her glamourous looks) early in her career featured in the core repertory operas, both Russian and Western, but as her fame rose she was featured in new productions or important revivals such as Manon, Thais, Romeo et Juliette, and La Traviata. It is also clear that when an artist of the stature of Antonina Nezhdanova from Moscow, made her annual St. Petersburg appearances, Kuznetsova had to share.

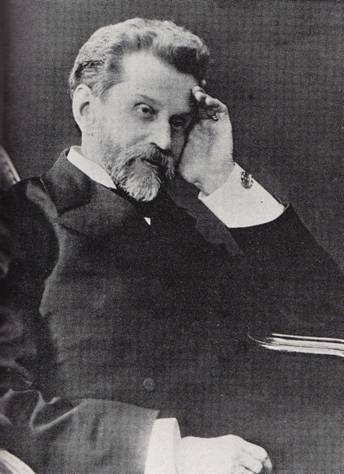

(Ivan Ershov as Tannhauser and Tristan, photos courtesy Joseph Stremlin)

When Chaliapin, always listed as a guest artist, arrives in St. Petersburg, the repertoire is arranged to accommodate his unique talents and the rôles he owned (such as Boris or Mephisto), a pattern almost everywhere he performed in the world during his mature career. He usually gave the Mariinsky about two months per season; he sings almost every second or third night, and the casts with which he performs very often have a star quality.

Like La Scala with its fixed 7 December opening night, the Mariinsky always opened its season on 30 August (Russian calendar), almost always with Glinka’s patriotic opera A Life for the Czar. For a few seasons Eugene Onegin, Ruslan and Lyudmila or Prince Igor were given on opening night. A typical season was a combination of mostly Russian operas and standard operas from the Western repertoire such as Carmen, Faust, Lakmé (very popular in Russia, even in the Soviet period), Les Huguenots, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser and La Traviata. After the Lenten break there was often what could be called a Wagner festival withthe four operas of the Ring Cycle, and Tristan und Isolde. Guest artist Félia Litvinne and Ershov were often the stars of these operas in the first fifteen years of the last century. Litvinne’s appearances as Brünnhilde and Isolde in Russian (she sang these rôles in other important world theatres in German, French and Italian) were often season highlights. A rare opera no longer performed in either Russia or the West, Judith by Alexander Serov, was also frequently given with Litvinne as Judith and Chaliapin as Holforenes; the images of Chaliapin in this part have become very famous, a visual explanation, if ever needed, of his stage greatness.

(Chaliapin, Holforenes, Judith, C.Mintzer coll.)

(Chaliapin, Holforenes, Judith, C.Mintzer coll.)

A singer about whom I was particularly interested, and now because of this chronology, he has his performance details at the Maryinsky laid out in print. Fifteen years ago I acquired an autographed photo of Ivan Melnikov in his creator rôle Tokmakov in Rimsky-Korsakoff’s The Maid of Pskov (Ivan the Terrible). He was also the creator of Boris Gudunov, Prince Igor, and The Demon as well as a host of other Russian operas. I wanted to know much more about this important artist and over the years I was able to cobble together a fuller appreciation of his amazing career; the work of chronologer Charles Jahant was especially helpful. It seems that for over thirty years he was singing leads at the theatre almost every third night. It is unfortunate that the very useful artist index in the back of Volume II failed to pick up his performances. And Nina Koshetz, who sang in the Mariinsky’s last season, also failed inclusion in the index.

This weak indexing has become a problem now that we use computerized data to organize information. A similar problem exists with the recently-published, two volume, monumental Vienna Staatsoper annals (Chronik Der Wiener Staatsoper, 1869-2009). It is clear that all the data was entered on computers and the resultant books were really a printout of the summary of the computerized information. Yes, only computers can sort and organize this huge amount of information, and we are grateful for that, but it would be a wonderful bonus if the resultant product, pre-publication, could be diligently analyzed by experts to spot bad computer output, mostly having to do with inconsistent spellings, and some bad data entry. We live daily with such computer problems as part of modern life, and this is the small price we pay for the enormous amount of data given us.

A positive feature of these books is the inclusion in bold print of additional valuable information, which I like to describe as “feeling” or the “texture of society,” like when a particular performance was a benefit for some patriotic or charitable institution, a significant anniversary or jubilee, or a serious political development. On 14 November 1866 we are told of a performance of A Life for the Tsar that “In celebration of the wedding of Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich, the Imperial Heir, Tsarevich, and Maria Fedorovna, Tsarevna and Grand Duchess. Before the performance Gala March (composer Siegfried Saloman) was played.” On 22 February 1894 there is a gala performance with excerpts from some of his operas, Swan Lake, and scenes from Verdi’s Falstaff “in memory of P. I. Tschaikovsky for the benefit of the composer’s monument in the St, Petersburg Conservatory and for the musician’s relief fund.” (Tchaikovsky had died four months earlier).

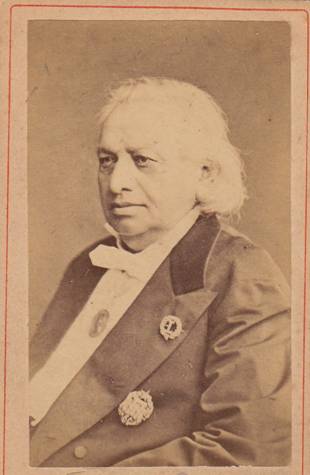

The author also highlights the frequent benefits in honor of performers like a Melnikov, towering figures like bassos Osip Paleček and Osip Petrov, or the conductor/composer Eduard Nápravnik, who it seems conducted the majority of the performances covered by these volumes; absolutely amazing!

(Edouard Napravnik and Osip Petrov, coll. Charles Mintzer)

When one speaks of “feeling,” the love this theatre’s public had for Tchaikovsky’s two great operas Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades constantly leaps off these pages. If one opens Volume II (1890-1917) to any page at random he is likely to see listings for these works with almost all the important appropriate singers on the roster performing them at different times. This is another example of the value of a running day-by-day chronology.

A very helpful feature is that all the early entries for Boris Godunov give details of which scenes were included in those performances, a treasure for scholars.

As far as I can tell, thus far, the only serious weakness in this monumental work are the incomplete index and the lack of a consistent method to denote débuts. An occasional embarrasing error does occur such as the Puccini La bohème on 17 October 1890. There are no photographs. Operanostalgia has supplemented this review with a photo gallery of representative stars of the Mariinsky.

Fryer and his team have used sensible and conventional transliterations of the Russian names, thus making the books more friendly for non-Russian readers.

In summary, these volumes are a “must-have” for collectors of opera house and singer books. Both Paul Fryer, his Russian research team and the publisher are to be congratulated for producing this incredible work. Note: I was in a very small way involved with this project three years ago, and thus acknowledged. CM)

The two volume work is available from the Edwin Mellen Press; these books are not inexpensive, but the publisher is offering the set for a very reasonable price, one to a customer, through December 2010. I urge anyone interested in this massive and important work to contact the Edwin Mellen Press.