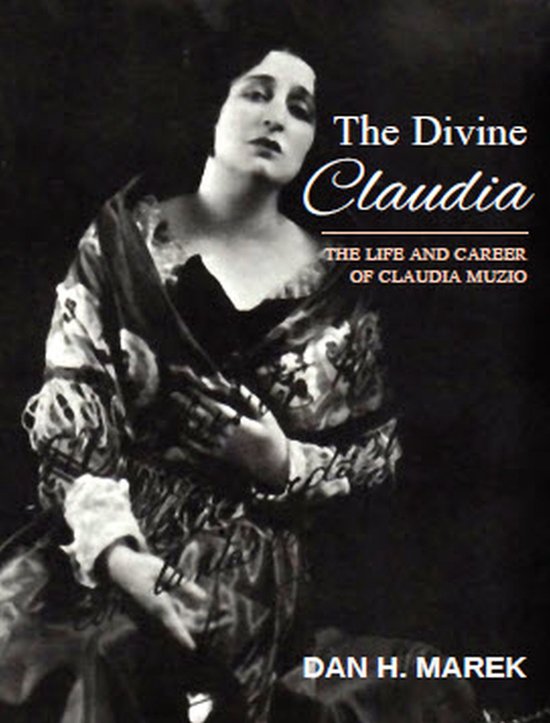

195 pages; Gatekeeper Press Columbia Ohio 2021. Click here to order the book !!!!!

The Divine Claudia-The Life and Career of Claudia Muzio by Dan Marek

195 pages; Gatekeeper Press Columbia Ohio 2021. Click here to order the book !!!!!

On the hard cover of this book author Dan H. Marek presents himself as “a principal tenor with leading opera companies including the Metropolitan Opera”. Mr. Marek has his own definition of “principal” as most opera visitors wouldn’t call “Remendado” (Carmen), “Lamplighter” (Manon Lescaut), “Joe” (La fanciulla del West”), “slave” (Salomé), “Borsa” (Rigoletto), “Captain” (Anthony and Cleopatra) principal roles unless you consider his “Beppe” (Pagliacci) or “Arturo” (Lucia di Lammermoor) to be more important than Canio and Edgardo.

This biography is a self-publication as “the suits” who rule the publishing world won’t anymore allow a biography of a famous singer. Sales too small to print. A lot of one’s opinion of this book depends on one's level of tolerance as Mr. Marek probably was not able (or didn’t want) to ask someone with a little bit of knowledge of operatic history to check his spelling. I admit my tolerance went downhill as page after page is riddled with mistakes. They can be hilarious such as Mussolini born in 1983 but most of the time they just irritate like “Stracchiari”, “Ornassis”, “Donde lieta uschi” and dozens of others. Marek doesn’t have a clue on the difference between “é” and “è” in French and probably thinks “Chènier” has the same pronunciation as “Chénier”. Sloppiness? Laziness? Or just ignorance?

The book follows year by year Muzio’s life and career. It soon becomes clear the author heavily leans on a chronology published on pages 149-173. In Marek’s bibliography there is a reference to a Muzio chronology by a certain Thomas Kaufman but on the pages themselves no mention of shameless copying of Tom’s work is to be found. Nor is there any trace (not even in the bibliography) of the several articles in The Record Collector; even when Marek copies almost word for word parts of John B. Richards’ “Corrections, Additions, Comments” in volume 28 Nos 5&6 of that magazine. Similar with most articles in TRC we are in for the dreaded treatment of “she sang W with X and Y in Z and then travelled to A where she sang B with C and D in E and always with success”. Chapter after chapter. Sometimes this rehash in longer words of the chronology is interrupted by a paragraph on an artist Muzio sang with. It somewhat breaks the tedium but in my opinion that’s why footnotes exist. Mr. Marek has a habit too of discussing Muzio’s records the moment she takes on a new role in the theatre; even if the records were made much later.

One thing is clear. The author has mined the many articles and/or books published on the soprano but he didn’t try to resolve less known patches of Muzio’s life and career by his own research. Therefore the soprano remains a shadowy figure. Marek repeats that’s what she wanted all along but I have my doubts. Yes, Muzio didn’t attend after performance parties and she often didn’t speak a word during rehearsal. But the author throws out of hand the Met’s general manager Gatti-Casazza’s words on the soprano :“Tantrums, whims, long faces, rebellious attitudes of a prima donna of forty years ago”. Gatti’s complaints are not so farfetched as Muzio knew her own worth and didn’t accept meekly favours given to Ponselle at the Met or Raisa in Chicago.

Marek gives us the opinion from some of her colleagues that Muzio was somewhat nun like. Nuns usually don’t have years long sexual relations with their married agent and after it’s over they definitely don’t marry a man seventeen years their junior who disappears from the book without a trace at the soprano’s death. Nor do we get exact information on Muzio’s financial troubles. Her manager squandered her money Marek writes but we don’t get an amount. Apart from the Met where fees are easily found in the archives we don’t get figures but they surely were high; especially in South-America.

The author admits that even in dire straits the lady never forgot she was a prima donna assoluta; the owner of a thirty-room villa where she rarely appeared, travelling with 99 trunks, only staying in the most expensive hotels, wearing costumes by a Parisian haute couture designer. And this all to her dying moments. Marek is convinced the lady remained a star to her last days and never asks why Columbia only consented to record Muzio at the end of her life if she herself paid for it (a friend did). That doesn’t resemble much confidence in Muzio’s selling power.

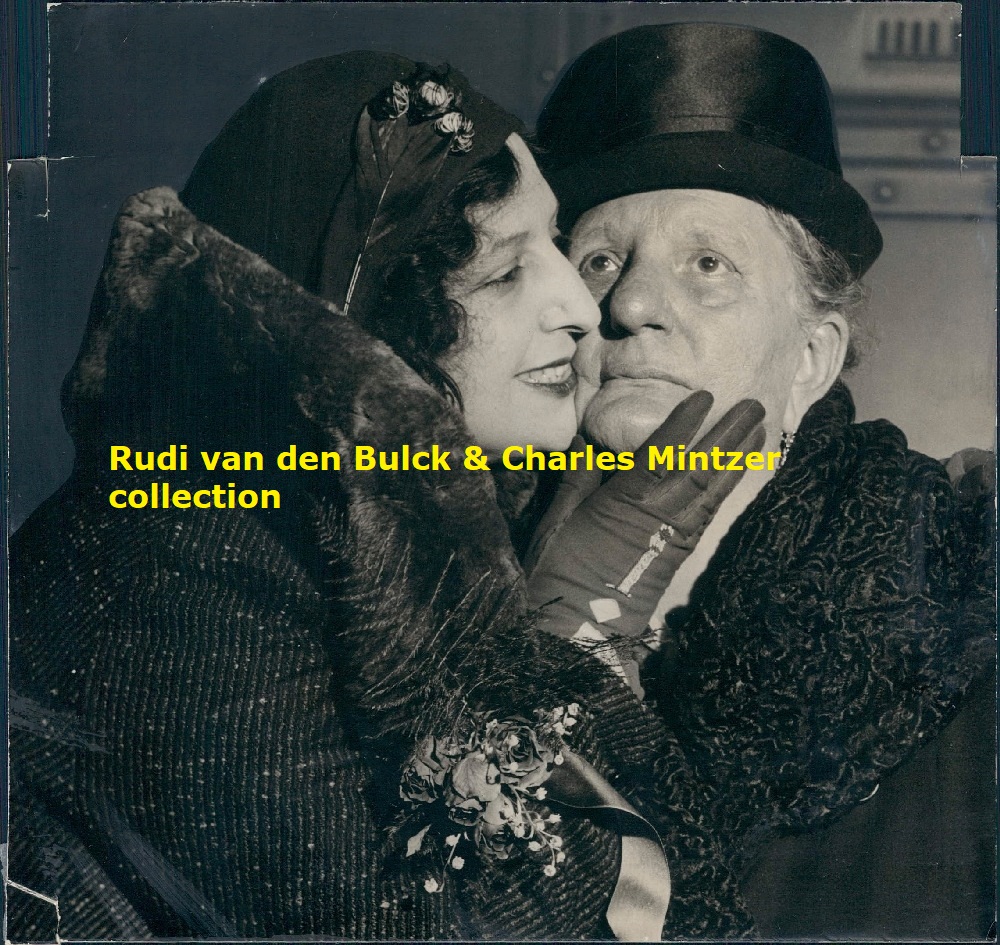

The book is illustrated with a lot of small grainy photographs; all in opera poses. There is no personal photograph of Muzio and family (especially her mother who was always at her side) or members of her “caravan”. Marek mentions her beauty and her regal tall figure: five feet nine inches. That gives her an extra ten centimetres on Caruso; yet on a photograph with her he measures a few centimetres more. A last complaint: in the chronology it is acceptable that other singers only get the first letter of their Christian name but in the text itself it is disruptive when some colleagues get the full treatment e.g. Enrico Caruso while others still are U. Di Lelio. Many web sites are devoted to historical singers where you can easily find their Christian names.

(Muzio and her mother)

(Muzio and her mother)

Agreed, up to now this review doesn’t sound positive. Nevertheless I doubt very much the already mentioned “suits” will accept a thoroughly researched and very complete biography by a scholar. This means that for now and probably for the long future this is the only biography of the soprano in English.

Notwithstanding all the warts it is an introduction to her life and her roles and all basic facts are correct. The Muzio articles in The Record Collector date from the early seventies (corrections in 1983) and are not readily available to everybody and probably not up to date.

Luckily the book has a few redeeming factors. Marek is fine on her relations with Licinio Refice and her creation of the priest-composer’s best known work: “Ceclia”. On the other hand the most famous opera she created (“Il Tabarro”) gets short shrift.

Personally I would have liked a discussion of Muzio’s recordings in one chapter and not dispersed throughout the text (with the exception of the Columbia records) but nowadays everyone who heard her in the theatre has gone. All we have are the records.

As said Mr. Marek was a comprimario and obviously knows a lot on singing. His judgments are fair and well written. He is a fan but he doesn’t idolize Muzio. Indeed he is somewhat severe; especially on Muzio’s earliest attempts. Marek correctly emphasises the difficulties in recording sopranos during the acoustic area but he rightly finds a lot of beauty in her Pathés and Edisons. His discussion of the famous late Columbias is state of the art. He is at his best when describing Muzio’s voice and interpretations.

Marek succeeds in luring us to our collections to listen once again to the divine Claudia.

Jan Neckers, April 2022