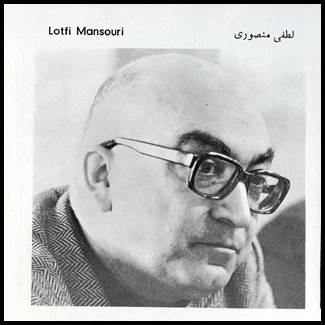

Lotfi Mansouri in an undated photo at Tehran Roudaki Opera House,

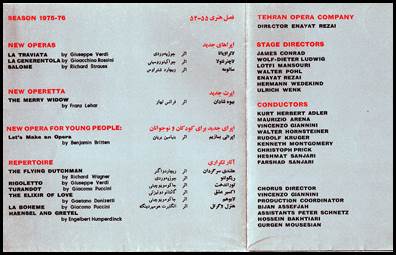

Almanac 1975-76, published by Roudaki’s Hall Public Relations

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

Lotfi MANSOURI (1929-2013) at Tehran Roudaki Hall Opera House in Iran

A Remembrance by Liliana Osses Adams

(Based in part on the memoir: An Operatic Journey by Lotfi Mansouri and co-authored by Donald Arthur, 2010.)

Lotfi Mansouri, an eminent Iranian-born artist, singer and actor, stage producer, manager and general director, and 2009 Opera Honoree of the National Endowment for the Arts, who dedicated his life to opera as “the greatest art form created by human mind,” died at his Pacific Heights home in San Francisco on Friday, August 30, 2013, at the age of 84. The cause of his demise was pancreatic cancer.

The Mansouri family, his wife Marjorie Anne and their daughter Shireen, requested donations in lieu of flowers to the San Francisco Merola Opera Program Adler Fellows, where the future of opera was created in Lotfi Mansouri’s master classes, or to the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto, headed by Lotfi Mansouri for twelve years (1976-1988).

Those of us who have felt his love and have shared his operatic life are touched by sorrow at his passing.

Lotfi Mansouri in an undated photo at Tehran Roudaki Opera House,

Almanac 1975-76, published by Roudaki’s Hall Public Relations

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

Lotfollah “Lotfi” Mansouri was born in Tehran, on Saturday, June 15, 1929, under the blazing sun, at the beginning of a hot summer. He described that day in the first chapter of his memoir: “Paradoxes in Persia, p.13:

It was a sweltering June day in 1929. At my parent’s home in Tehran, my mother, Mehri, was undergoing a very difficult birth. It was so painful and bloody that the midwife thought both mother and baby would probably die. As soon as I emerged, they put me on a block of ice and turned all their attention toward saving my mother’s life (…)

As I lay on my ice block, my mother’s life was saved. When I began gurgling, somebody finally looked at me. Apparently I was going to make it, too. It was considered a miracle that I had survived, so my grandmother named me “Lotfollah,” Arabic for “kindness of God.” When I was finally shown to my mother, she screamed with fear and pushed me away. She couldn’t cope with having a baby. She was only fifteen.

Lotfi’s mother, Mehrangiz Jalili (nicknamed Mehri), was married to an older man, Hassan Mansouri in pre-arranged marriage. She was a Christian convert, related to the Qajar aristocratic dynasty. He was a Muslim. She was a cultivated, passionate and intelligent woman. In her salon, where the elite guests were entertained by reading poetry of Hafez and Omar Khayyam, she played the old tunes on tar (long-necked Persian lute). She was fluent in French and translated the short stories of Alphonse Daudet into Farsi (the Persian language).

Lotfi’s father came from a prosperous family of landowners and merchants/bazaaries. He was trained as a lawyer but he never practiced in the court. He was distant, authoritarian, composed, undisturbed, and self-possessed (although sometimes he showed the softer side of his character towards his wife and her only child.)

In his teens, Lotfi had to study the Bible and to recite and memorize verses from the Koran. It seems that he grew up in an environment full of contradictions. In time, he became a bit confused by living in two different households. However, he was never forced to choose between his parent’s backgrounds, their tradition, and their religion.

From those early days he took refuge by watching Hollywood movies in the classic old style of glitz and glamour made popular in the 1930s and 1940s. He often skipped meals, rushed to the theater and hooked up there for hours. He vividly recalled his favorite musical star, Deanna Durbin, giving her stunning soprano performance in an English translation of “Nessun dorma”, the tenor aria from Puccini’s Turandot, heard as “None shall sleep”, in the movie “His Butler’s Sister,” directed by Frank Borzage, or her rendition in English of Cio-Cio-San’s aria from Puccini’s Madama Butterly, “Un bel di” (“One fine day”), from the 1939 film “First Love.” He secretly dreamt of Hollywood and of a chance to meet her.

(Actually he never developed any affection or interest for the Iranian traditional music or for the long vocalizes of Oum Khalsoum, admired throughout the Middle East. Her improvised singing brought the audience into a euphoric and ecstatic state of mind. She significantly influenced many artists, including Maria Callas.)

It was in the north of Tehran, at Shemiran, where Lotfi began his preschool experiences. In the following, often repeated anecdotal quotation from his memoir (p. 20), he revealed his first drama of peeing on the stage during his debut performance:

I was attending a coeducational kindergarten not far from our home in north Tehran. One of my classmates was the future shah’s youngest sister, Fatemeh Pahlavi. Our teacher organized a class play, and she and I starred in the show.

I was the Grand Vizier, while Fatemeh played the Queen. A new world was dawning. Unfortunately, the crown prince himself, along with his mother, the real queen, and his two sisters, decided to attend our little performance. I knew who he was and got so nervous that I wet my pants and started crying onstage. From that moment, I developed a lifelong sympathy for singer’s nerves.

In June 1947 he obtained the high-school diploma from the prestigious Firooz-Bahram, the all-boys’ gymnasium in Tehran under the Zoroastrians teachings and beliefs (e.g., of free will). Soon after, his father insisted on a career in medicine and made a choice for his further education: he had to become a doctor and he had to study medicine in Scotland, at the University of Edinburg. It was not what Lotfi had in mind or what he desired.

Finally, after months of urging, his father relented and gave permission to study medicine at the University of California in Los Angeles, UCLA, in Southern California where there were (and still is) a large Iranian Diaspora.

Was he close to fulfill his dreams and to come across his beloved movie stars in Beverly Hills?

In October 1947 eighteen-year-old Lotfi Mansouri – equipped with a nice tenor voice, a foreign student’s visa and a monthly allowance from his father to cover personal and living expenses – embarked on the ship “SS Marine Jumper” to America. Does he have doubts about the whole venture? Does he have enough power to control what will happen in the future? Certainly, his decision involved great risk and uncertainty; but, at the same time, exposed his adventurous nature. At that moment, he left behind the Muslim way of life, the whole hadith and responded to his destiny, to the will of fate, to kismet.

In the next chapters of his memoir, entitled: “Lotfi in La-La Land,” “The Swiss Connection,” and “Iranian Intermezzo,” he recalled his successes and failures, and the highlights of his personal and artistic life.

In the fall of 1948 he enrolled to study psychology at UCLA, where he completed his undergraduate degree in 1953.

(He would later say that “I saved so many patients by not becoming a doctor.”) His father was less than satisfied with Lotfi’s failed medical study. As consequence, he stopped his monthly “stipend” and asked him to return home.

Being an émigré, he was forced to support himself by singing at weddings and funerals. In his bright new car and with his driving license, he went from one odd job to another, “tooling” the LA freeways. He cleaned houses, did gardening, was a cashier in a Hollywood supermarket, and an usher at a theatre. Sometimes, he would meet an usherette, Carol Burnett, a famous comedienne and singer. He got his first singing job at UCLA in the musical by Irving Berlin “Annie Get Your Gun” with Carol Burnett in the title role. He also sang duets with Burnett at rallies for the future president, Richard Nixon. Thus began their lifelong friendship.

In the mid-1950s, as a young student, he began musical and operatic activities at UCLA Workshop Studio under direction of Dr. Jan Popper. He still remembered his first stage experience in the chorus of Benjamin Britten’s student performance “The Beggar’s Opera”, conducted by Jan Popper. Next, at UCLA student productions, he sang various roles ranging from the lyric Orfeo (Monteverdi), Ferrando (Così fan tutte), to the spinto Rodolfo (La Bohème), and dramatic roles of Lohengrin, Otello, and Laca in Leoš Janáček’s Janůfa.

On September 18, 1954, he married Marjorie Anne Thompson (nicknamed Midge), a beautiful girl from an esteemed Wisconsin family, whom he met at UCLA. Their marriage “brightened and enriched” their lives for almost six decades.

One day in 1956 at UCLA, Sam Adams, a talent agent, told him that he looked a little bit like Enrico Caruso and asked him if he would like to play Caruso in a short film about the Italian singer? Soon after (replacing Mario Lanza and Richard Tucker as first choice), he had been cast in the lead role of Caruso in “The Day I Met Caruso” about a little girl enchanted with Caruso’s voice, directed by renowned Hollywood director, Frank Borzage. In the half-hour TV show, telecast on September 5, 1956, Lotfi Mansouri lip-synched arias to the original Caruso recordings of Aida, La Bohème, Tosca, and Pagliacci; even though, as he said, “he could sing the arias by himself.”

Well, after the next segment the whole series, called “The Screen Director’s Playhouse,” was cancelled by NBC.

(In coming years, Lotfi Mansouri was again associated with the film industry. In 1981, he produced the opera scenes in “Yes, Giorgio,” starring Luciano Pavarotti, and in 1987, in “Moonstruck” with Cher and Nicolas Cage.)

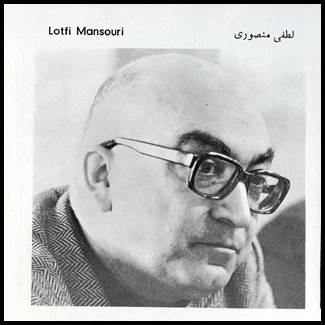

Lotfi Mansouri as Caruso

Source: Lotfi Mansouri “An Operatic Journey”

© University Press, 2010, p. 43

In 1957 he was awarded a scholarship to study voice with Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, which she helped to establish in California, after her retirement from the stage. During the summer music camp, he participated in concerts and master classes under the distinguished Maurice Abravanel, an American conductor of Iberian Sephardic origin. In following months, still aspiring for a long professional career as an operatic singer, he was coached privately at Lotte Lehmann’s home “Orplid” in Hope Ranch at Santa Barbara.

(For more about Lotte Lehmann, please scroll down to “Lotte Lehmann League” website by Gary Hickling:

http://lottelehmannleague.org

During 1957-60 Lotfi Mansouri received an appointment as an associate professor at UCLA and worked, as a team with Natalie Limonick (chairwomen of Workshop Studio and a former assistant to Dr. Jan Popper.)

His directorial career started almost accidentally: by dislocating his elbow when jumping from a rock in one of the Workshop productions. Unable to continue with singing, his schedule in 1956-60 included directing operas at Los Angeles City College: Mozart’s Così fan tutte, Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, and Puccini’s Il Tabarro and Suor Angelica, and at UCLA: a double bill performance of Darius Milhaud’s Les malheurs d’Orphée and Fiesta, followed with Claude Debussy’s Pelléas and Mélisande, and “Vanessa” by Samuel Barber with libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti.

Around that time, at Marymount College, the Catholic University at Palos-Verdes, he directed several Broadway musicals, such as: Jerome Kern’s Roberta, conducted by the Viennese born Robert Wagner (with technical advice from Bob Hope) and “The King and I,” the musical by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, based on the fictionalized novel about the royal governess “Anna and the King of Siam” by Margaret Landon.

These productions demonstrated his extraordinary potential for creating operas while he placed a special emphasis on reading the composer’s score (as the starting point) before advancing his own directorial ideas.

From the beginning of his career he had commented that: “… the function of operatic production was to illuminate the meanings and values of the musical and verbal text, to search for and externalize hidden significance and subtexts, and, using intuition and a full armory of acquired skills, to bring the true meaning of each opera as close to the awareness of the audience as possible – in short, to read between the lines, without neglecting to read the lines.”

In the quest for professional recognition, the following years brought him new challenges and opportunities.

During the summer of 1959 at the Music Academy of the West, thirty-year old Lotfi Mansouri was chosen to prepare scenes for the master classes of Dr. Herbert Graf, an Austrian-American opera producer from the Metropolitan Opera in New York. He also worked as Dr. Graf’s assistant on a production of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, conducted by Maurice Abravanel and was chosen to sing the tenor buffo role of Monostatos. Dr. Graf’s successful production at the Lobero Theatre in Santa Barbara used, for the first time in America, the original 1816 scenic designs created by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. His years at UCLA “turned out to be my operatic boot camp. I gained a ton of experience as a singer, actor, director, designer, prop master, dramaturge, coach, and administrator.”

During the summer of 1960 he participated in the young artists’ program founded by Friedelind Wagner at Bayreuth Festival. Then, he was meticulously coached and trained in singing and stage-directing under Walter Felsenstein, an Austrian theater and opera director and founder of the innovative Komische Oper Berlin (in former East Berlin, 1947.)

He noted: “The whole master class experience, in both Bayreuth and Berlin, was beginning to get to me – and it wasn’t all positive. I regarded the theater as a never-ending quest for human truth, not as a sanctuary for worshipers…”

His hectic summer brought a new opportunity: he became an assistant to Dr. Graf for the production of Verdi’s Otello, presented in the picturesque setting within the arcaded courtyard of the Doge’s Palace in Venice. It was staged for the first time in August 1960, under the baton of Nino Sanzogno with the cast of legendary Mario Del Monaco, Tito Gobbi, and Marcella Pobbe.

At that time, he gradually drew himself into the métier of stage director and his dream to pursuit a career as an operatic singer was definitively over: “I never did get very far as a tenor”, he concluded.

In 1960 at the invitation of Dr. Graf, Lotfi Mansouri became resident stage director at Zurich Opera, where, under his mentor and artistic father, he learned and polished his craft. Prior to residency in Switzerland, he became U.S. citizen.

Mansouri’s first directorial assignment at Zurich Opera was the European premiere of Gian Carlo Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors, sung in German, just in time for Christmas holidays.

During six years (1960-66), he directed a total of eighteen productions for the opera and several other productions for the International Opera Studio – a training program for young artists launched by Dr. Graf, where he was appointed a director of drama classes. He finally experienced the challenges for which he had always strived. His repertory was mixed and included standards by Verdi, Bizet, Rossini, Donizetti, Saint-Saëns, Meyerbeer, and Beethoven. He also premiered Leonard Bernstein’s one-acter “Trouble in Tahiti,” and a Broadway musical “Carnival!” based on the 1953 movie “Lili” with Leslie Caron.

His opera productions in various genres and styles “were as theatrical as possible without distracting from music.”

In 1966 his subsequent engagement – as head stage director – brought him to Genève Opera under directorship of Dr. Graf. During ten years (1966-1976) at the Grand-Théâtre de Genève, Lotfi Mansouri directed a total of thirty-four productions of larger-scale for the opera and other productions for the Centre Lyrique – yet another development program for young artists founded by Dr. Graf.

From 1963 Lotfi Mansouri’s increasing guest-directing invitations arrived from various opera houses in Italy, Austria, Germany, France, Netherlands, Canada, and North America, including Chicago, Houston, Santa Fe, Philadelphia, San Diego, Dallas, New Orleans, San Francisco, and both the Metropolitan and New York City Opera companies.

In May 1971 the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Arts, and Roudaki Hall Director, Enayat Rezai personally invited Lotfi Masouri to join Tehran Opera as guest stage director in a production of Bizet’s Carmen. He described his first visit at the theatre as follows: “I was driven in a chauffeured car to the shiny new opera house for a tour. I could not help but be impressed. Designed By Fritz Bornemann ¹) the architect who had built the Deutche Oper in West Berlin, it had everything: a turntable, modern rigging and lighting equipment, spacious backstage areas, a breathtaking foyer, mosaics, chandeliers, lush gardens. It was a dream of a building in a sleek, modern district flanked by glamorous corporate headquarters, hotels, and arts and entertainment palaces. The whole area was constructed with Westerners in mind.”

During his journey home, he reunited with his father, whom he had not seen in twenty-three years.

¹) there’s a discrepancy between names, ch.3, p.85: Tehran Roudaki Hall, built in 1967, was designed by an Iranian-American architect (of Armenian origin), Dr. Eugene Aftandilian (Ugene Aftandiliyans); the auditorium of the building had capacity of about 1060 seats and was partly modeled after the Vienna State Opera.

(Source: „Das neue Kaiserliche Hoftheater in Teheran,“ Bühnentechnische Rundschau, Februar 1968.)

In the country, where no activities existed in domain of Western traditional opera, the prestigious Roudaki Hall (Talar-e Roudaki) had become a center for discovery, development and promotion of young operatic talent and a source of national pride and artistic creativity. The Roudaki theatre housed Tehran Opera Company, Iranian National Ballet Company and Tehran Symphony Orchestra performing operas, ballets and classical concerts, and hosted hundreds of renowned and celebrated international artists.

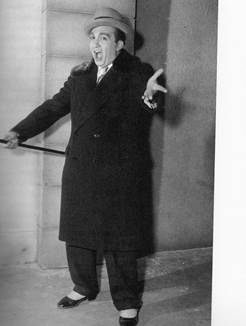

On October 26, 1967, the Coronation of HIM Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1919-1980), and the Shahbanou, Empress Farah Diba, was the glorious occasion for the inauguration of the newly built modern opera house in Iran. During the Gala Opening Night, two one-act operas were presented, inspired by Persian legend: directed by Monir Vakili Zaal and Roudabeh by Samin Baghtcheban, derived from Ferdowsi epic Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) by Ahmad Shamloo, and Jashne Dahguan (The Peasant Feast) by Ahmad Pejman in stage production by Enayat Rezai with scenic design by Theo Lau. The cast was exclusively Iranian, led by lyric soprano Monir Vakili and bel canto baritone Hossein Sarshar. The esteemed Heshmat Sanjari conducted the Tehran Symphony Orchestra. The unbelievable and spontaneous commitment of a team of artists working together virtually around the clock made this particularly happy beginning worthy of its best efforts. To recognize this remarkable accomplishment, Their Majesties received the artists in private audiences, asking them the following question: “Would you like to help us to continue in this way in which you have just helped us to begin?”

Their Imperial Majesties at Roudaki Hall in Tehran, October 26, 1967.

Source: The Imperial Couple of Persia. Burda Druck und Verlag Offenburg.

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams)

In 1966 the Tehran Opera Group, later referred as Roudaki Hall Opera House, was taken in charge by its first manager, thirty-one year-old, Enayat Rezai, who made his debut as stage director during the Coronation. The recipient of the Pahlavi Imperial Order of Homayoun Lion and Crowned Sun, he guided his young company with confidence, courage and commitment, pursuing an active career as chief producer and also as operatic singer.

In 1976 he was succeeded by Bijan Assefjah (Ahsefjah), educated in Iran and the United States and trained by Lotfi Mansouri as stage director and singer in drama classes at the International Opera Studio in Zurich.

In May 1971 the poster designed by renowned Sadegh Barirani, an Iranian graphic designer, announced the performances of Bizet’s Carmen; it was printed in silkscreen technique at the workshop of Graphic Art Center in Tehran.

Poster designed by Sadegh Barirani, 1971

Source: © Sadegh Barirani Website

During May and June, 1971, Lotfi Mansouri directed his first Carmen under the baton of the Bavarian conductor, Hans Walter Kämpfel with sets designed by Theo Lau and with costumes designed by Helen Ensha. The cast included: Evelyn Baghtcheban, alternating with Pari Samar as Carmen, Albino Toffoli and Nicola Martinucci as Don José, Hossein Sarshar as Escamillo, Monir Vakili and Alenoush Melkonian as Micaëla, Soudabeh Safaieh as Frasquita, Vahideh Fatourechi as Mercédès, Alek Melkonian as Remendado, and Enayat Rezai as Moralès.

Bizet’s Carmen at Roudaki Opera House, 1971

Enayat Rezai as Moralès and Monir Vakili as Micaëla

Photo Credit: Bijan Bani-Ahmad. Source: © Monir Vakili Official Website

Afterward Lotfi Mansouri wrote: “the opening night went pretty well. I was pushed downstage to take a curtain call, which I normally don’t do, and the audience showered me with flowers and applause. At that moment, my father realized that his son’s chosen profession might not be so bad after all. He may have forgone a medical career in favor of going into this odd trade, but he had clearly made a name for himself.”

Lotfi Mansouri surrounded by the cast of Carmen, Roudaki Hall, 1971

Source: © Lotfi Mansouri - Opera in Action Official Website

Meanwhile, the far-reaching campaign launched behind the scenes to appoint him to the position of Director of Tehran Opera never materialized, although, he was invited by Mr. Mehrdad Pahlbod, Iran’s Minister of Culture and Arts to became an artistic adviser to the company during 1974-75 season. In coming years Lotfi Mansouri’s directorial assignments included production of five new operas: Verdi’s Aida and Falstaff, Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, and a double bill of Ravel’s L’heure espagnole and Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, “… all featuring many leading international artists like Giuseppe Taddei, Beverly Sills, and Tito Gobbi.” (Actually, Beverly Sills did not perform at Tehran Opera House and Tito Gobbi appeared as Jago in the 1974 Enayat Rezai production, after original 1973 stage directing by Federik Mirdita.)

The particularly stimulating nine-month lyric season at Roudaki Hall, which ran from October 1972 through June 1973, offered all new productions of Aida, Faust (with Cesare Siepi as Méphistophélès giving a special representation attended by Their Majesties), L’Elisir d’Amore, Manon (Massenet), Il Tabarro as curtain-raiser for Gianni Schicchi, Loris Tjeknavorian’s Pardis and Parisa (with libretto of Mahmoud Khoshnam), and Gian Carlo Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors (translated into Persian by Enayat Rezai), in a double bill with Help, Help, The Globolinks! (Persian words by Mahmoud Khoshnam). From the repertory the company chose: Tosca, Otello, Der fliegende Hollander, and Die Zauberflöte.

Assembled in 1972 the Tehran Opera and Ballet Orchestra of sixty musicians, mainly from Eastern Europe (Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland), and joined by their Iranian colleagues, released the Tehran Symphony Orchestra from its dual duty of performing opera and ballet productions. The chorus of almost fifty members was of Iranian and Armenian origin, and the company maintained an intensive training program for the comprimarii.

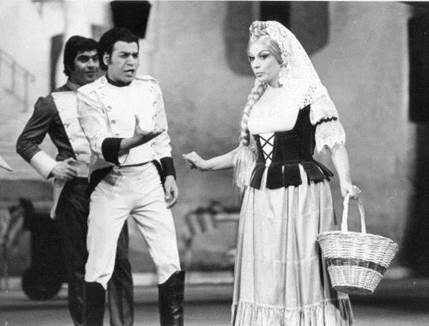

On Saturday, October 7, 1972, for the opening of the season, Verdi’s Aida performance in stage direction by Lotfi Mansouri brought a stylish and cosmopolitan audience to the theatre, which matured beautifully during the years.

Poster designed by © Sadegh Barirani, 1972

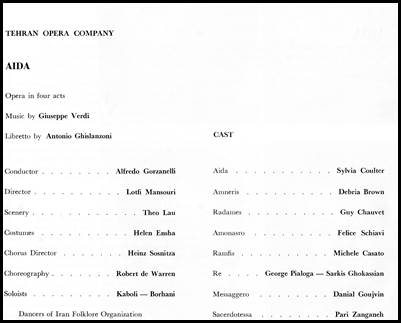

In the following days of October 10, 14, and 29, renowned international singers: Guy Chauvet (Radamès), Sylvia Coulter (Aida), Debria Brown (Amneris), Felice Schiavi (Amonasro) were supported by the cast of resident singers: Michele Casato (Ramfis), George Pialoga and Sarkis Ghokassina (Re, the King of Egypt), Messaggero (Daniel Goujvin), and Pari Zanganeh (Priestess Voice of Sacerdotessa).

Cast list for Verdi’s Aida at Roudaki Hall, October 1972

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

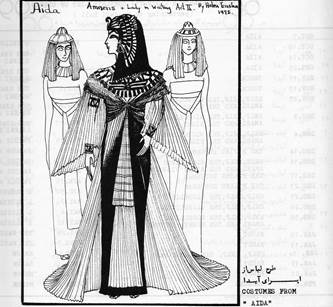

The company principal stage designer, Theo Lau and Helen Ensha, costume designer, ensured that the sets, costumes, jewels, and props were as authentic as possible. The supernumeraries as spear carriers fashioned for the clean-shaven Egyptian army, the Ethiopian slaves and prisoners, priests and priestesses crowded the stage with a magnificent display of ancient Egyptian splendor.

Giuseppe Verdi’s unfolding drama of two lovers doomed by the jealous and vindictive princess Amneris was placed under masterful baton of Alfredo Gorzanelli, who conducted all performances without score.

So, the magic began…

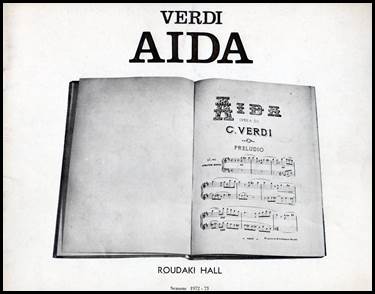

Program cover page: Verdi’s Aida at Tehran Roudaki Hall, October, 1972

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

²) there’s a discrepancy between dates: Verdi’s Aida was performed in Tehran only in 1972 and not in 1974, as listed in APPENDIX B} PRODUCTIONS DIRECTED BY MANSOURI, p. 303.

While Aida did not return to repertory for the next six seasons, Debria Brown, an American operatic mezzo-soprano with great interpretive talent and deep powerful voice, was greeted enthusiastically as Amneris (a last-minute replacement for Michèle Vilma). When the curtain falls late at the evening, eclipsing Aida and Radamès in dying embrace, Amneris’s begging for peace “Pace t’imploro” mesmerized the audience. After impassioned performance as Amneris, Debria Brown revisited Tehran Opera House as Mistress Quickly (Falstaff 1975) and Herodias (Salome 1976).

Costume design for the première at Roudaki Hall, 1972

Sketch by Helen Ensha: Amneris and Lady in waiting, Act II

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

For the season 1973-74, running October 1973 – June 1974, the Roudaki Hall offered an impressive and delicious blend of various styles from bel canto to opera comique and operetta, including modern German musical theatre. The most anticipated productions were six new operas: Boris Godunov, at the top of the season, followed by Turandot, Adriana Lecouvreur, Les contes d’Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann), Carl Orff’s Die Kluge (The Clever Girl), and Der Zigeunerbaron, at the closure of the season, presented in Persian translation by Mahmoud Khoshnam with the cast of Iranian soloists. In addition, the company produced the revivals of Tosca, Madama Butterfly, Così fan tutte, Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail, Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Il Tabarro as curtain-raiser for Gianni Schicchi, and Carmen, the most frequently performed opera at Tehran Roudaki Hall.

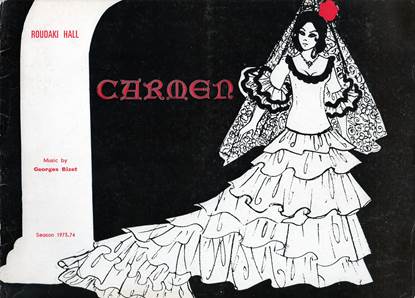

Program cover page designed by Helen Ensha: Bizet’s Carmen at Tehran Roudaki Hall, 1973

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

In November 1973 Lotfi Mansouri offered a reprise of Carmen from 1971 featuring Pari Arianpour (Samar) in the title role of Carmen (Iranian guest singer, who also appeared as Pari Samar), Hila Gharakhanian (Micaëla), Sudabeh Safaieh (Frasquita), Leonor Hajari (Mercédès), Pedro Lavirgen (Don José), Giulio Fioravanti (Escamillo), Daniel Goujvin (Dancaire), Alek Melkonian (Remendado), George Pialoga (Zuniga), and Enayat Rezai as Moralès. The entire opera ensemble gave a special representation in attendance of Their Majesties, the Shah and Shahbanou.

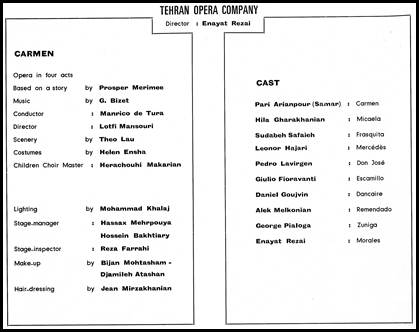

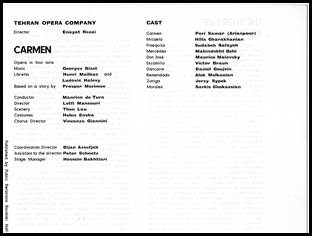

Cast list for Bizet’s Carmen at Roudaki Hall, November 1973

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

After six months, in May 1974 Lotfi Mansouri returned to Roudaki Hall as guest director for production of Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann (Les contes d’Hoffmann). He offered an interesting mise-en-scène under the baton of Maestro Manrico de Tura, opera’s principal residing conductor.

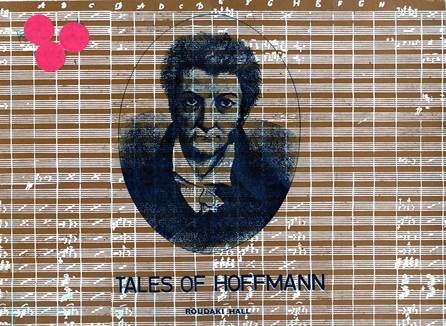

Program cover page with portrait of E.T.A. Hoffmann, Tehran Roudaki Hall, May 1974

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

The scenery and costumes were designed by Wolfram Skalicki in collaboration by Amerei Skalicki. The choir ensemble was led by distinguished Vincenzo Giannini.

Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann at Roudaki Hall, May 1974

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

The leading role of Hoffmann was sung by Nicolas di Virgilio opposite Rudolf Constantin, who sang four villain roles of Lindorf, Coppélius, Dapertutto, and Miracle. Apart of two invited guest singers, the entire cast included the company permanent solo roster, headed by Monir Vakili in three soprano roles: The Muse, Giuletta and Stella, Hoffmann’s unreachable love.

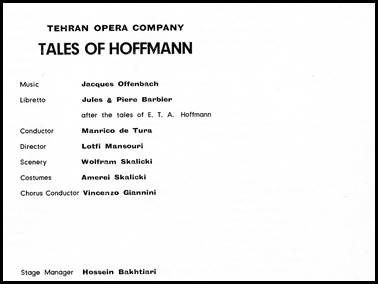

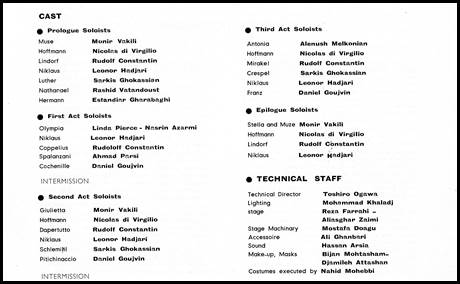

Cast list for Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann at Roudaki Hall, May 1974

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

During 1974-75 artistic season, running September 1974 – June 1975, Roudaki Hall, under direction of Enayat Rezai, presented ten new productions in cooperation of Lotfi Mansouri, one-season artistic advisor to the company, and with a new appointed coordinator director, Bijan Assefjah. The season opened on September 22, 1974, with Don Carlos (with Giorgio Tozzi as Philipp II), followed by Smetana’s Die verkaufte Braut, Verdi’s masterpiece Falstaff (with Giuseppe Taddei in the title role), Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (with Luciana Serra), Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel (translated into Persian by Enayat Rezai), a double bill of Donizetti’s Il Campanello and Orff’s Carmina Burana, Ravel’s L’heure espagnole as curtain-raiser for Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, and Britten’s Let’s Make an Opera! (Persian words by Amir Ashraf Arianpour). From repertory the company chose: La Bohème, Madama Butterfly, Otello (with Tito Gobbi as Jago giving a special representation in attendance by Their Majesties), Loris Tjeknavorian’s Pardis and Parisa, Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci in a double bill with Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, and reprise of Bizet’s Carmen from the previous season, directed by Lotfi Mansouri with Pari Samar in her signature role opposite Maurice Maievsky as Don José and Victor Braun as Escamillo.

Bizet’s Carmen at Tehran Roudaki Hall, May 1975

Maurice Maievsky as Don José and Pari Samar (Arianpour) as Carmen

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

Cast list of Bizet’s Carmen at Roudaki Hall, May 1975

On Febraury 1975 Lotfi Mansouri mounted a new production of Verdi’s 1893 final opera “Falstaff” with Giuseppe Taddei in the leading role, who gave one of his greatest acting and singing performances as the fat, old, delusional English knight.

Program cover page: Verdi’s Falstaff at Tehran Roudaki Hall, 1975

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

In his memoir, Lotfi Mansouri wrote at Mansouri’s Gallery of Illustrious Colleagues, p. 278:

Another great baritone was Giuseppe Taddei, a Genoese darling and a great talent. He started as a Verdi baritone, and I directed him in Chicago as Mustafá in L’italiana in Algeri with Marilyn Horne. I later took him to Tehran as Falstaff. He had an uncanny way with a text, bringing such sophistication to comedy. He was not a buffo – he drew the comedy out of the situation. He knew what Shakespeare meant when he gave this grotesque character a noble title: he was always SirJohn.

Lotfi Mansouri’s Falstaff with Giuseppe Taddei, conducted by Kenneth Montgomery and designed by Theo Lau (scenery) and Amrei Skalicki (costumes) featured the following performers: Robert Kerns as Ford, Alek Melkonian as Fenton, Daniel Goujwin as Dr. Caius, Renato Ercolani as Bardolph, Jerzy Sypek as Pistol, Alenush Melkonian as Mistress Alice Ford, Sudabeh Safaieh, alternating with Nassrin Azarmi as Nannetta, Leonor Hajari as Mistress Meg Page, and Debria Brown as Mistress Quickly.

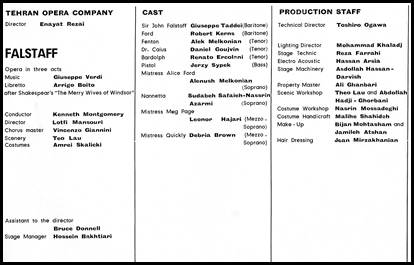

Cast list of Verdi’s Falstaff at Tehran Roudaki Hall, 1975

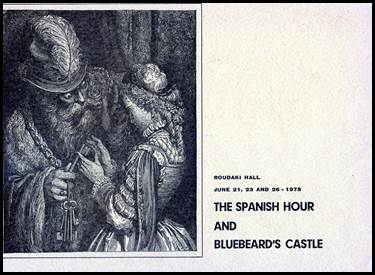

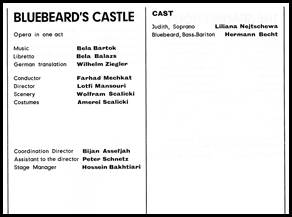

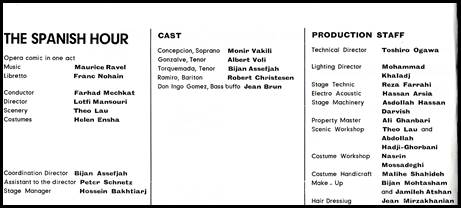

At the closure of 1974-75 season, instead of originally scheduled production of Franz Lehár’s Die lustige Witwe, by Lotfi Mansouri with Kurt Herbert Adler at the pit, Roudaki Hall presented Ravel’s The Spanish Hour (L’heure espagnole) in a double bill with Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, dates: 21, 23, and 26 June, 1975.

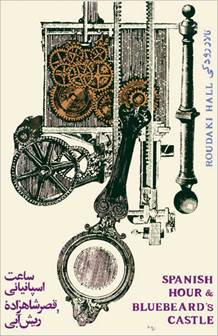

Poster designed by © Sadegh Barirani, 1975

The production was staged by Lotfi Mansouri under the baton of largely acclaimed Farhad Mechkat.

Program cover page: Ravel’s The Spanish Hour and Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, Roudaki Hall, 1975

(Courtesy Liliana Osses Adams collection)

The scenery and costumes were designed by Wolfram Skalicki with assistance by Amerei Skalicki. The Bluebeard’s Castle was performed in German translation by Wilhelm Ziegler with Liliana Nejtschewa as Judith and Hermann Becht as Bluebeard.

Iranian leading soprano, Monir Vakili sang the role of Concepción in Ravel’s The Spanish Hour opposite Bijan Assefjah in tenor part as Torquemada.

Monir Vakili as Concepcion and Robert Christesen as Ramiro, Roudaki Hall, 1975

Source: © Monir Vakili Official Website

Robert Christesen as Ramiro, Albert Voli as Gonzalve, and Jean Brun as Don Ingo Gomez completed the cast.

Cast list of Ravel’s The Spanish Hour, Tehran Roudaki Hall, 1975

³) there’s a discrepancy between dates: Ravel’s L’heure espagnole and Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle were performed in Tehran in 1975 and not in 1972; Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann were performed in 1974 and not in 1973, as listed in APPENDIX B, p. 303; Mansouri’s production in Tehran of Verdi’s Falstaff was not included.

As Tehran Roudaki Hall Opera House approached its 1975-76 season under successful directorship of Enayat Rezai nothing of extraordinary would forecast the troublesome events. The entire ensemble made their best efforts to present an elaborated line-up of eleven operas. Yet another invitation for Lotfi Mansouri to join the company in directing a new production of Lehár’s The Merry Widow with Kurt Herbert Adler at the pit was cancelled.

Season 1975-76 at Tehran Roudaki Hall Opera House

During that time, the Shah of Iran dismantled the existing two-party system and, by establishing the single political party Rastakhiz (Resurrection) not only agitated people on the streets, but his reign on the Peacock Throne was nearly at the end. Regardless, March 19, 1976, manifested another event of grandiosity with the institution of the Sal-e Shahanshahi (The Year of the King of Kings) by adopting a new Imperial calendar which broke with the Islamic chronology; the year was no longer 1355 – consistent with the migration of Prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina, but 2535 – a year marking the conquest of Babylon and the foundation of Persian empire by Cyrus the Great. Shockingly, two days later, during Persian New Year (Now Rooz), Enayat Rezai was suddenly dismissed from his post as General Director of Tehran Opera Roudaki Hall, the company which he created and served passionately during ten years. Therefore, the season continued as scheduled until June 1976 under direction of Bijan Assefjah (Ahsefjah.) Finally, at the opening and the closure of the last 1977-78 season, the company offered new ambitious productions of Carmen, portrayed by Pari Samar in stage direction by Bijan Ahsefjah. Once in full blossom, the ephemeral history of Tehran Roudaki Hall Opera House ended in the wake of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

In June 1975 Lotfi Mansouri bid farewell to Tehran Roudaki Hall Opera House questioning himself: “Were my best efforts raising cultural level of the average Iranian? Hardly.”

In 1971 his arrival as guest director at the opera house for the production of Carmen was “greeted like a rather shiny penny from heaven.” Immediately, as he recalled, he “hurled” himself into his new assignment. “Money wasn’t an issue; as a matter of fact, there was no budget. I was simply told I could have whatever I wanted. Still, after so many years at major international opera houses, flagrant extravagance simple wasn’t in my blood.”

In chapter six of his memoir “Back on Track”, Lotfi Mansouri detailed his production of Aida, p. 97:

While I used the unlimited budgets to put handsome productions on the stage, mounting an Aida unequaled for elaborate trappings by any theater in the Western world, other members of the staff were busy telling the financial authorities they needed more money for materials I had ordered, then promptly stuffing that largesse in their own pockets. Nepotism had become a driving force at the theater, with everybody’s friends and relatives on the take. The nepotism grew so rampant I began to wonder if there weren’t perhaps a couple of overpaid camels on the payroll.

I never knew where I stood with anybody. Any number of barnacles on the hull of the opera company took it amiss when I tried to teach them some discipline and responsibility. They were determined to undermine my position wherever they could.

As years passed, Lotfi Mansouri’s operatic journey in Tehran went “from bad to worse.” He found himself “in the middle of a political situation that was slowly but surely coming to a boil.” And he continued: “As a native son with a Western lifestyle, I found myself constantly approached by people eager to share their experiences with me, and many of those experiences were harrowing.”

And then, he added:

As if this weren’t rough enough, the pressure for me to resettle in Iran was unrelenting. The culture minister told me how necessary my services were for my homeland, both as an opera director and a television producer. Everywhere I went, people were constantly telling me how ungrateful I was for not having long since accepted this generous offer. Every time I went back to Geneva, I was a nervous wreck, and it was taking more and more time for me to recover.

Lotfi Mansouri’s “audience” with the Shah of Iran, 1974

Source: Lotfi Mansouri “An Operatic Journey”

© University Press, 2010, p. 93 (extract)

Finally, he “managed to negotiate” his “departure from this forced sojourn in a golden cage” and ended the chapter as follows:

In 1979, the Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini returned to Iran after fourteen years in exile and removed the shah from power. Under Khomeini’s doctrinaire regime, there was no room in the culture for opera or other frivolities of that nature, and so the opera house was converted into a venue for religious plays. I imagine it’s probably still rife with intrigue and corruption, and doubtless, to this day, somebody’s camel has its name on the payroll.

(With all due respect and regret, Mr. Mansouri’s peculiar narrative seems, at some points, a bit confused and unfair, especially in today’s context, towards young and talented Iranians trying to revive Roudaki theatre past glory by recent performance of the enthusiastically welcomed Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi, the first Italian opera in decades, set modestly and brilliantly accompanied on two grand pianos at Vahdat Hall, the former Roudaki Hall.

Please scroll down to video clip: IRAN – Italian Opera in Iran by © Press TV Videos: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6a9aREIkiCk

After production of the Ravel-Bartók double bill, and being “released” in 1975 from his function as an artistic advisor to Tehran Roudaki Hall, Lotfi Mansouri never returned to Iran; instead of the scheduled production of Lehár’s The Merry Widow at the closure of 1975-76 season with Kurt Herbert Adler at the podium, the new administration replaced Mansouri-Adler with Wilfried Steiner as stage director and Hans Peter Raucher in the orchestra pit.

On his return from Iran to Geneva, Lotfi Mansouri’s ten years tenure as head stage director at the Genève’s Grand-Théâtre (1966-1976) included thirty-one opera productions; he premiered with Johann Strauss Jr. The Fledermaus under the baton of Carlos Kleiber and ended with Lehar’s The Land of Smiles (Das Land des Lächelns), conducted by Carlos Kleiber with the orchestra de la Suisse Romande.

In chapter six “Back on Track”, Lotfi Mansouri wrote:

My final production was Franz Lehar’s eminently forgettable bit of ham-handed chinoiserie, The Land of Smiles, in a French version entitled Le pays du sourire. I jokingly referred to it as Le pays du Mansouri, and I had every reason to smile as I mounted it. Sixteen years earlier, I had arrived in Europe as an eager but inexperienced director. Now I was a seasoned and well-known professional, with a mile-long list of credits at major opera houses on three continents. In Dr. Graf I had found the mentor of a life time.”

Sadly, on April 10, 1973, Dr. Herbert Graf lost his battle with cancer. It was also a tremendous loss for Lotfi Mansouri. Their admiration was mutual, as was their friendship and professional partnership. Was he in the fast lane to succeed him? Not likely. But, “at the Grand-Théâtre, the intrigues and political games began, as everyone jockeyed for position in anticipation of Dr. Graf successor. I tried to protect Dr. Graf from the gossip and rumors.”

And, in the same chapter six, Lotfi Masnouri concluded:

Dr. Graf’s successor as director of the Grand-Théâtre de Genève was a Frenchman from Alsace-Lorraine by the name of Jean-Claude Riber. Apparently the board passed over me because I wasn’t French enough, or perhaps because I was too close to Dr. Graf. Like most incoming directors, Riber let it be known in no uncertain terms that everything before him had been garbage and that under his direction the Grand-Théâtre would finally assume its place among the greatest opera companies in the world. I could feel the negative vibes the minute we met. I think my closeness to his predecessor made him feel insecure, and it clearly seemed that he was jealous of my experience at so many major opera houses (…)

In the years to come, I would manage to expunge Jean-Claude Riber from my memory, but he did make one odd reappearance in my life. Some time in the mid-1980s, I saw him out of the corner of my eye, lingering in the back of the lobby after a performance at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. With no appetite whatsoever for another encounter, I raced for the door, hoping he might pretend that he hadn’t seen me, but he stopped me in my tracks and was effusive in congratulating me on my recent appointment as general director of the San Francisco Opera. I put on my Persian cat smile and told him that I owed it all to him: after all, without him, I might still be stuck in Geneva. He took it as a compliment.”

Though, before reaching the San Francisco Opera on the West Coast, Lotfi Mansouri’s operatic journey led him across the ocean to the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto. In following chapters, entitled, among others: “North of the Border”, “From Provincial to World Class”, “Open Your Golden Gate! “Leaving My Heart,” and “An Operatic Voice for North America,” Lotfi Mansouri gives detailed chronicles of his professional and personal life by pointing to his successes and failures, joy and sorrow, love and hate, friendship and betrayal. Hailed by many, still for some skeptical, his characteristic “Persian smile” did not always serve him well or inspire confidence, and, ugly enough, he was accused of being an untrustworthy, arrogant showman.

In 1976 Lotfi Mansouri was named general director of the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto and he held this position for twelve years, until 1988. His first directorial assignment with the company was Verdi’s Don Carlos and he later produced an impressive list of forty-two operas, including some Canadian premieres, like: Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnburg; Janáček’s The Makropulos Case and Jenůfa; Britten’s Peter Grimes, Death in Venice and The Turn of the Screw; Alban Berg’s Lulu and Wozzeck; Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsenks; Tchaikovsky’s Joan of Arc, Ambroise Thomas’s Hamlet, and Donizetti’s Anna Bolena.

These followed with some standards like: Carmen, Faust, Boris Godunov, Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Die Fledermaus, Die lustige Witwe, Offenbach’s La belle Hélène and Les contes d’Hoffmann, and also included: Verdi’s Otello, Il Trovatore, Un Ballo in Maschera, Simon Boccanegra; Puccini’s La Rondine, Turandot, La Fanculla del West, and Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, Idomeneo, Die Zauberflöte; Umberto Giordano’s Andrea Chénier; Bellini’s Norma; Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde; Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, Elektra, Ariadne of Naxos, and Salome; Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea, and a comic opera by Arthur Sullivan and W.S.Gilbert’s The Mikado.

It turned out, that upon his arrival in Toronto the introduction of supertitles is considered as one of his most important operatic achievements launched for the first time in January 1983 during staging of Elektra at the city’s O’Keefe Centre. Apparently his idea, that the audience could visually follow the plot of foreign-language translated into English and projected onto a screen on the proscenium of the stage, came during the preparation of Monteverdi’s final opera.

In chapter nine of his memoir “From Provincial to World Class” Lotfi Mansouri remembered:

We were planning Monteverdi’s 1642 masterwork, L’incoronazione di Poppea, which has as complicated a story line as has ever been offered in opera. I was concerned about how to convey its intricacies to a modern audience that would be highly unlikely to have read the libretto first. Coming to a performance personally prepared was how it may have worked a century ago, but in our high-speed age, who has time?

And then he continued:

The introduction of supertitles (originally called surtitles) in Toronto may have been our most important accomplishment. For millions of people, they have made opera a comprehensible art form. Supertitles are the most democratic and liberating tool we can employ in the modern era.

Lotfi Mansouri credited mostly his wife, Midge for giving the idea when watching on TV the production of Wagner’s Die Walküre by Patrice Chéreau in Bayreuth, and as subtitles flashed by, Midge said, “You know Lotfi, this isn’t as dumb as I thought it was”. “And the idea was born.”

On the contrary to the repulsed purists and critics – the main opponents, because “they wanted to be the only ones who knew what was going on” (as Lotfi Mansouri jokingly said) – it didn’t take long for the opera houses to begin adopting the innovation by using the translation from the original language into the audience’s language, and the system spread internationally during subsequent simulcasts of live performances, making opera accessible for the public, as he often repeated, “I’ve always believed that opera is the height of music theater. I am also one of those simplistic people who believe that opera is for everyone.”

In 1988 Lotfi Mansouri had became distinguished fourth general director at San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, succeeding his predecessors: Gaetano Merola, a Neapolitan conductor who, by his arriving in San Francisco was not only enchanted by its charm but, he hoped he could benefit the city, by founding opera by the famous Golden Gate in 1923; followed by Viennese born, Kurt Herbert Adler, who began his association with the San Francisco Opera in 1943 as chorus director, and, in 1953 he replaced Merola as general director of the company which he ran for twenty-eight years, until 1981; followed by Canadian opera manager, Terence A. McEwen, who directed the company from 1982 through 1988, when he announced his resignation on the advice of his doctors.

In fact, Lotfi Mansouri’s relationship with San Francisco began in 1951 as “a dollar-per-show supernumerary” carrying a spear or marching in a procession onstage in Verdi’s Otello during San Francisco Opera tour at Los Angeles Shrine Auditorium. In the following chapter ten, entitled: Open Your Golden Gate! Lotfi Mansouri recalled:

I first directed a production at the San Francisco Opera in 1963. You might say it was love at first sight. I was invited back, season after season, and I always looked forward to my time in the City by the Bay and its jewel of an opera house. In 1988, to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of that first production, I heard I was going to be given a silver tray. Instead I was given the company.”

He made his San Francisco Opera debut in the 1963 season with production of six operas. It was one of the most fascinating seasons in the annals, and offered revivals of: Arrigio Boito’s Mefistolele, conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli with Giorgio Tozzi (Mefistolele), Sandor Konya (Faust) and Mary Costa (in double role as Marguerita and Elena); Bellini’s La Sonnambula, conducted by Richard Bonynge with Joan Sutherland (Amina), Renato Cioni (Elvino), Richard Cross (Rodolfo); Verdi’s La Traviata, conducted by Molinari-Pradelli with Mary Costa (Violetta) and Renato Cioni (Alfredo); Saint-Saëns’s Samson and Delilah conducted by Georges Prêtre with James McCracken (Samson) and Sandra Warfield (Delilah); Wagner’s Die Walküre, conducted by Leopold Ludwig with Amy Shuard (Brünnhilde), Regina Resnik (Fricka), Jon Vickers (Siegmund); and Poulenc’s The Dialogues of the Carmelities, conducted by Leopold Ludwig and with Lee Venora (Blanche).

As yet, having spent three previous seasons (1963-65) in San Francisco staging mostly revivals, his new production of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore under the baton of Giuseppe Patané, featuring Reri Grist (Adina), Alfredo Kraus (Nemorino), Ingvar Wixell (Belcore) and Sesto Bruscantini (Dr. Dulcamara), rewarded him with a ten-minute ovation at the premiere in Saturday Evening Series, and just about everybody who saw the performance “fell in love with Lotfi Mansouri.” (“50 Years of the San Francisco Opera,” by Arthur Bloomfield, 1972.)

During his association with the company for almost four decades, he had since staged and adapted more than seventy-five productions.

(For complete list of Lotfi Mansouri’ productions please scroll down to San Francisco Opera Official Website:

http://sfopera.com/About/Lotfi-Mansouri.aspx

Undoubtedly Mansouri’s greatest challenge during his tenure was leading the company through the seismic repairs and renovations of the opera building following the damage from the October 1989 San Francisco earthquake.

Amongst his accomplishments at San Francisco Opera, he is mostly credited for introduction of the “Pacific Vision” program to commission several new operatic productions, which have received critical acclaim, including

John Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer (1992), Conrad Susa’s The Dangerous Liaisons (1994), Stewart Wallace’s Harvey Milk (1996), André Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1998), Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking (2000), and Philip Glass’s Satyagraha premiered in 1989, after David Pountney’s 1980 original production, conducted by the late Bruce Ferden.

In 1992 Lotfi Mansouri had became a Chevalier of France’s Ordre des Arts et de Lettres.

In 2001 he was awarded San Francisco Opera Medal, the highest honor awarded to an artistic professional.

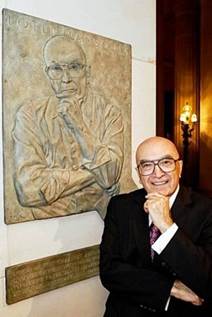

On October 26, 2009, an inscribed commemorative plaque in bronze of Lotfi Mansouri holding the music score was unveiled and permanently displayed in the main foyer of the San Francisco Opera with a quote: “Opera is the greatest artistic banquet created by the human mind with something for every taste.”

Mansouri’s figurative portrait had been commissioned to sculptor Bruce Wolfe, based in Oakland, California.

Lotfi Mansouri in San Francisco, October 26, 2009

Photo Credit: Drew Altizer

© Drew Altizer’s Photography, San Francisco

After thirteen years as general director of the San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, and fifty years in the world of opera, Lotfi Mansouri announced his resignation (and was succeeded by Pamela Rosenberg.)

As he was preparing the final production of Lehár’s The Merry Widow (Die lustiege Witwe sung in English,) he famously said: “One of the first things I learned in opera was that you need to make good entrances and exits. It’s time.”

It was, indeed, a great grand exit in style with Léhar’s spectacular production, waltzing immortal Viennese operetta. (Mansouri’s DVD recording with Yvonne Kenny (Hanna Glawari) and Bo Skovhus (Danilo), conducted by the late Erich Kunzel is available for purchase at amazon.com)

Coincidently, David Gockly who became sixth general director of the company announced Lotfi Mansouri’s death during the rehearsal of Boito’s Mefistofele – Mansouri’s memorable 1963 production – which opened the San Francisco Opera 2013 season.

Thank you Mr. Mansouri for everything you have done!

May his soul rest in peace. Rohesh shad.

In my acknowledgment, I wish to thank Rudi Van den Bulck, Editor of Opera Nostalgia for his continuous support and encouragement and to Director Enayat Rezai for his patient and diligent responses to my queries.

© Liliana Osses Adams

California, autumn 2013