2012, 231 pages. AU$45. Wakefield Press; 1 Parade West. Kent Town, South Australia 5067

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

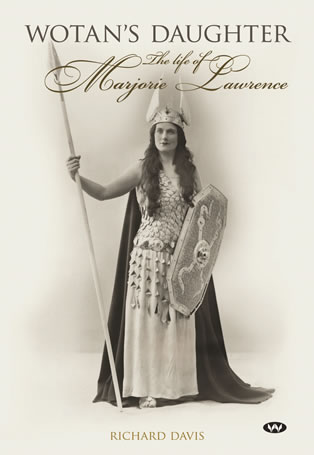

WOTAN’S DAUGHTER, The Life of Margorie Lawrence by Richard Davis

2012, 231 pages. AU$45. Wakefield Press; 1 Parade West. Kent Town, South Australia 5067

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

This biography/study of the legendary Australian Wagnerian diva is a most welcome contribution to the literature. It is a serious telling and analysis of an artist’s rise from a humble farm in Dean’s Marsh, Victoria, Australia to the heights of opera in Paris and New York with several stops in between.

The author at the outset informs the reader that in his opinion Marjorie Lawrence’s best-selling 1949 autobiography and the successful 1955 Hollywood film it inspired, Interrupted Melody, is a very selective telling of her story, almost a fabrication, but surely a good story and an inspiring movie. He tries to set the record straight re the half-truths from the book and movie as to her family life, her various lovers, and her early struggles to establish herself on the operatic scene. Opera enthusiasts will care little about the family dynamics and rifts re money and early relationships. We get a clearer description and analysis of her feud with the great Germaine Lubin when they sang together in Paris. Marjorie in her book describes Lubin as a jealous “has-been,” when in truth, when they sang together in “Lohengrin” in Paris in the early 1930s, Lubin was near the pinnacle of her fame and powers. Sure, Lubin saw in the young and athletic Australian a potential rival, but stress should be put on “potential.” How many established artists look all that kindly on a talented youngster coming up in the profession, performing “their” roles and who may have particular gifts (like an easy upper range) that threaten their supremacy. I am reminded of the anecdotes about Caruso feeling the competition with the young Hipolito Lazaro’s easy and ringing high C’s. All this proves is that singers, like most people, are human when they worry about the new competition, possibly embarrassing, justifiably or not.

(photos courtesy Charles Mintzer collection)

(photos courtesy Charles Mintzer collection)

Her first few years in Paris (1933-1935) were great for learning her craft, being exposed to opera production on a major level, and meeting leading figures and powers in the opera world. Marjorie was well trained by Cecile Gilly, the ex-wife of the famous Algerian baritone, Dinh Gilly, who left Cecile to live with Emmy Destinn. The author had access to rare documents outlining Marjorie’s student travails in the busy French capitol. Davis’ information shows the struggles a young singer goes through in finding the right teacher, finding the financing of the difficult and expensive student phase, and ultimately finding the “right” people who can put together all the elements into a “marketable” package. Marjorie found the right teacher; her talent was so promising that Mme. Gilly was willing to wait for her success as her “payback,” and Mme. Gilly had the right connections to launch her career in a methodical and logical way. Mme. Gilly at first thought her a contralto and developed her lower range, and only with that secure foundation in place did she then realize that Marjorie was really a dramatic soprano that she unleashed her great upper voice. She wasn’t quite ready to “take on” Paris, but was ready for smaller theatres, with Monte Carlo an appropriate starting point. Legendary impresario Raoul Gunzbourg, the guiding force in Monte Carlo, is here portrayed as something of a “dirty old man,” making unwanted sexual advances to the budding Aussie. But Marjorie had her success and was noticed by important figures in the profession, and after additional performances in the French provinces, was ready for a Paris debut.

In Paris she cut a significant swath and for the two years she shared the stage with Lubin. In her “Lohengrin” debut, Marjorie singing Ortrud to Lubin’s Elsa. Her roles in Paris were “Walküre” Brünnhilde, Salomè in “Herodiade,” Rachel in “La Juive,” Aida, “Götterdämmerung” Brünnhilde, Donna Anna, Brunnhilde in Reyer’s “Sigurd,” Salome in the Richard Strauss opera, Brangäne in “Tristan und Isolde” to Lubin’s Isolde, and Valentine in “Les Huguenots.” In 1946 she sang Amneris in a specially staged “Aida.”

In 1934 the Met had heard about this Aussie who was having great success in Paris and put out feelers, even offering her a contract when it looked as though Frida Leider would not re-sign for the 1934-35 season, but the thought of relearning the Wagner roles in German and her overall inexperience made Marjorie delay the Met for at least another year. And, of course, as everyone knows, the Met solved the Leider problem by engaging an unknown Norwegian soprano, and the rest is history.

Author Davis never claims that Marjorie was in Flagstad’s league as a vocalist, but he definitely feels she did belong in the upper echelons of her voice category. Unlike Lubin, Flagstad was very gracious and welcoming to the newcomer, who sang most of her Wagner roles, but never Isolde and Kundry. Lawrence had the luxury of observing the leading Wagnerian Met singers and this in turn added to her vocal sophistication. After Flagstad left the Met and Lawrence was felled with polio, Helen Traubel was elevated to the company’s principal Wagnerian soprano. When Lawrence was ready to resume her career, on a limited basis, and in re-staged settings to accommodate her disability, Traubel gave the Met an ultimatum. If Lawrence was accorded star status as Isolde, the Met would have to find themselves another Brünnhilde. This is the first time I had seen this spelled out so definitively; Davis’s source for this is information is from an early draft of Marjorie’s book. That “bombshell” paragraph was excised from the final edition, presumably for legal reasons, probably because it was more rumor than a documented fact, although clearly Marjorie believed it to be true. Marjorie also felt that Melchior was unhappy with the attention her “return” to the stage was receiving, that he was not the genial colleague generally portrayed by the media.

America, being so vast a country with so many individuals vying for fame, publicity plays a large part in the creation of a star, even in the classical music field. Marjorie in her career had two events that put her on the “front pages:” her daring and exciting mounting of the horse Grane in the final pages of “Götterdämmerung” and riding with great flair into the funeral pyre. This was sensational and it was “front page” material. Her other publicity coup was less happy; her contracting polio in 1941, just when she was about to take over for Flagstad who chose to go back to her homeland Norway for the duration of the war. The loss of the use of her legs and being confined to a wheelchair was a great story from a publicity point of view, but behind those sad images was an even sadder story. The medical fight to regain the use of her legs and the need to continue performing took a toll on her personal life and her finances. When she finally gained enough strength and will to perform, her various concerts and the few specially-staged operatic performances were greeted with great love and sold-out signs, but there was always the undercurrent that these events had an element of sensationalism and played to the audience’s pity. Marjorie wanted to be accepted as a great singer, not an object of pity. Over the next ten-plus years she made an amazing number of appearances and performances from her wheelchair, concerts, some opera creatively staged, fund-raising events, tours for the fighting forces (American. British, and Australian) as an example of courage and the dream to eventually triumph. I think she felt her greatest honor in this period was her White House appearances, especially those for Franklin Delano Roosevelt, also a polio survivor who rose above his infirmities.

Author Davis, who has written about great Australian musicians, knows the classical musical field, and makes only a few factual mistakes, which is not so rare when one is writing of the musical scene in other countries. He states that Marjorie was interviewed on a Met intermission during a Victoria de los Angeles/Jussi Björling “Manon” performance. (Björling never sang des Grieux at the Met) Davis may have the right date for the interview, but such a performance never took place; these things can be easily checked on the Met’s fabulous database.

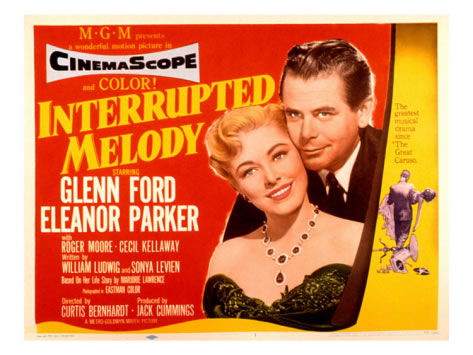

Because the book was so interesting and Lawrence’s story, as told by Davis, so gripping, I viewed the DVD of Interrupted Melody once more. As a sample of a Hollywood biography it has many virtues, but for an opera historian who knows the basic facts of her story, the movie is pure fantasy. It gets the broad outline of her story correct, but the details and the chosen operatic examples are all wrong. Marjorie had hoped in 1954/55 when the movie was being made, that MGM would use “her” voice on the soundtrack, but the studio thought otherwise. Her almost 50 year old voice which had significant wear on it was deemed by the studio brass to be inappropriate, especially for the earlier part of her career. Eileen Farrell covers herself in glory in the soundtrack, expertly synched by Eleanor Parker. The film has Doctor Tom King, her eventual husband, entering her life in 1932 (Monte Carlo debut) instead of eight years later, thus eliminating a series of male companions and lovers. But it is a good film, and apparently, according to Davis, despite her misgivings, Marjorie agreed it was excellent and uplifting telling, if not her real story.

The book does not have a day-by-day chronology although the contours and details of her career are well suggested in the narrative. To the extent that opera singer biographies are still being written today, a chronological tabulation is “de rigueur.” There is a very detailed discography with lots of supplemental information, as Lawrence was heavily recorded “off the radio,” not so many commercial recordings. A superb feature of the book is the documentation revealed in the “end notes.” Davis is able to back up most of his research with these detailed citations, a big plus from the researcher’s point of view. This book is a good “read” as Marjorie Lawrence’s story is so compelling. Recommended.

Charles Mintzer