(photo courtesy René Seghers)

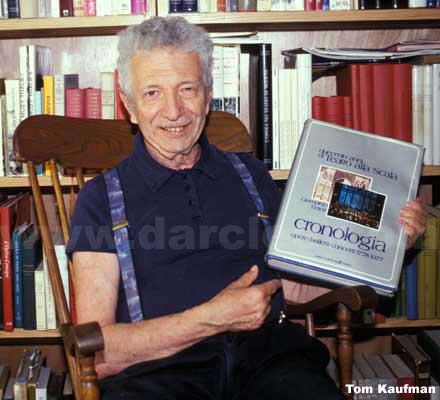

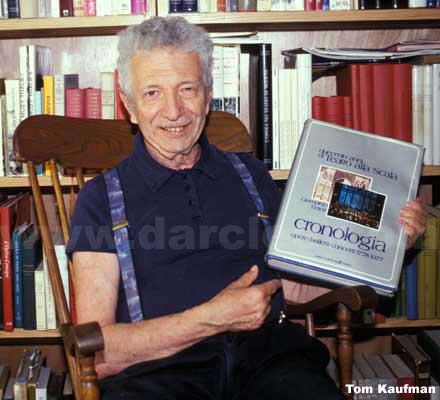

(photo courtesy René Seghers)THOMAS KAUFMAN (Vienna 6 July 1930- Baltimore 22 April 2010) in memoriam

(photo courtesy René Seghers)

(photo courtesy René Seghers)

Dear Tom Kaufman died Thursday the 22nd of April 2010, age 80, in a Baltimore, Maryland nursing home.

Tom was not like anyone else I ever knew. He was an “original” as they now say. He was a gentle soul who couldn’t bear to listen to La Bohème as the death of Mimi was unbearable for him, it would dissolve him in tears. Yet, he was not a Puccini person at all; his heart was with Pacini, Mercadante, Donizetti, Meyerbeer and the other greats of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; although he had a passion for Verdi, especially the early operas that contained elements that harkened back to the composers he most loved. I think his all-time favorite opera was La Juive, but, strangely, he hated Eleazar and thought him a criminal. Tom was a political conservative, but on some subjects he could be amazingly liberal. He wanted lower taxes, but could care less about bedroom issues; in American terms something of a libertarian.

Tom’s research in opera performances and performers was vast. His library resources were probably better than any major university library, and always growing. We were always comparing notes and gossip about new books of interest either just published or in the gestation stage. But having all this data was not an end in itself, although on occasion it seemed to be, because Tom loved sharing his information with other researchers. His main enthusiasm, as with his favorite composers, was opera in the vast Spanish-speaking world, not only Spain but also Central and South America, I think, because the operas and composers he cared about most were popular in that culture. But Tom cast a wider net and wanted to know about the whole world. He could get as excited about a book about opera in Slovenia as well as a book about opera in nineteenth century Valencia. His book VERDI AND HIS MAJOR CONTEMPORARIES – A Selected Chronology of Performances with Casts is a major contribution to the history of opera performance. If you want to know the cast of the first Aida in Hanoi or Calcutta, this is where you must go. Tom’s chronologies were an individual art-form. His technique was to break seasons into the nineteenth century mold built around Christian holidays, even if the material he was documenting was not appropriate to that formula. It was one of his many eccentricities. Yet his published chronologies for the Donizetti Society, and the Patti, Battistini, Caruso, Ponselle, and many other books are not likely to be improved upon.

Tom did not have an easy life; born in Vienna in 1930, a refugee in Paris in the late 1930’s and ultimately an American citizen. Tom’s love of America was without qualification. Tom served his country in the armed forces as a young man, and in retrospect told several stories about those young years and his interesting encounters, and the improbable friends he made for life. Although Tom in his life’s journey ended up as a very patriotic American, there was a European sensibility at work in his personality. I have been told by the editor of Operanostalgia that when Tom had the opportunity, he loved speaking in German. He also had a good command of Italian and Spanish.

In a conversation a few years ago I was quite surprised to learn that Tom personally had not seen all that much opera in person, considering he lived in New York with its huge operatic possibilities, and later the New Jersey suburbs before moving to Baltimore about ten years ago. His wife Marion was a rock in his life; in his Verdi book just mentioned he lists Marion as his research assistant and he dedicates the book to her. On my first visit in the late 1970’s to their home in Boonton, New Jersey I referred to an article in that morning’s New York Times which at that time was “must reading” for people of their age group and background. Marion said, “We do not read the New York Times, we read the Washington Times; we are conservative!”

Tom was a scientist who worked for a large pharmaceutical company, writing technical product descriptions that had to pass muster with the Federal Drug Administration. He was apparently very good at his work. Tom considered himself a connoisseur of food, and would take his guests to Asian buffet restaurants; partially for the plentiful and not particularly costly food, and as a diabetic he could find dishes that were safe for him and also tasty.

Although Tom did not go to a lot of opera in person, his record collection was vast. He had a particular passion for the heroic tenor voice. The composers he most loved often wrote great tenor arias with martial cabalettas, and this was what Tom most admired. He had a passion for the voices of Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, John O’Sullivan, and Nino Piccaluga, and of the more modern period Mario del Monaco and Luciano Pavarotti, tenors who could deliver these thrilling arias with concluding ringing high notes. Of the non-high-note tenors he especially liked Jose Carreras, I think, for the sheer gorgeous beauty of his voice. He did not particularly admire Placido Domingo; not his kind of tenor. And he was starting to warm to Juan Diego Florez, especially his forays into off-the-beaten-track early repertoire.

One of Tom’s “teases” was to talk about the opera Norma as though it should be renamed Pollione. It was never the Callas, Sutherland, or Caballe Norma but rather the Fillipeschi, Corelli, or Del Monaco Norma. We once had a heated and lengthy discussion as to whether La Gioconda was essentially a soprano or tenor vehicle. As a case can be made for either position, I maintained that no opera company would mount that opera without a suitable soprano protagonist; he disagreed, and made a case that this opera was often mounted as a vehicle for a Gigli or a Tucker. The one thing about Tom was that you could argue and disagree with him on the merits of an issue, opera or political, and it did not affect our underlying friendship. He knew his positions were not especially “main line,” in fact, he relished going against political correctness or the perceived given wisdom of the day. This played out in his love of Meyerbeer and dislike of Wagner. He was certain that it was the academics and elite opinion makers who had brainwashed us in the twentieth-century to downgrade his beloved Meyerbeer and put up Wagner as the great and seminal composer all should admire and worship. He did like Lohengrin and Walküre for their tenor arias, but he would take the Huguenots over all of them. Tom was very active in the movement to elevate Meyerbeer to what Tom believed to be his proper and larger place in the overall scheme of things.

Tom will be missed on several levels, his compassion, his generous hospitality, his love of country, and his unflinching positions on operatic matters. Personally, I was about 180 degrees from him on operatic and political issues, but was 100 percent with him as a colleague and friend.

Charles Mintzer. April 2010