John Boni on his personal experiences with Mario Del Monaco

When my son, Mario, was three years old I heard a troubling raspiness in his voice, to me an ironic condition because his full Christian name is Mario del Monaco Boni, after the great Italian singer, Mario del Monaco whose death almost twenty-five years ago on October 16 closed the chapter on that rare operatic creature — the heroic tenor.

Mario had not yet been born when I visited his namesake him at his villa in Lancenigo just four months before he died. There I discovered that in a small way I had touched the life of a boyhood hero who had touched my own so enormously.

I was a teenage del Monaco groupie, long before the word was coined. From my home in South Philadelphia, (only two blocks from the birthplace of Mario Lanza, for whom my tailor father made a suit), I Greyhounded to the old Met in New York to hear him sing. My Uncle Bruno, a fixture in the Met standing room line during the forties and fifties, held a place for me. Through the kindness of him and his cronies I saw Mario in Otello, Ernani, Carmen, Andrea Chenier and in Maria Callas’ extraordinary Met debut in Norma. In those days, I had the extra bonus of the Met touring company and my trip to Philadelphia’s Academy Of Music were mercifully shorter.

In college I met other del Monaco fanatics who would also cut classes to hear Mario sing. (Incidentally, we’re always on a first name basis with our heroes, a familiarity that somehow brings them closer to us. It’s never Mays, Snider, Mantle. It’s Willie, Mickey, the Duke and … Mario. In opera, as in baseball, passions about our heroes run high and loyalties are forever.)

It was during those collegiate trips to the Met that I fashioned a banner out of a twenty-four foot long roll of shelf paper on which I painted the legend, “Bravo, Mario, il re dei tenori,” (Bravo, Mario, king of tenors). We brought it to each performance and hung it from the old Met’s dress circle or balcony railing during final curtain calls. When Mario emerged, my Uncle Bruno and other standees now at the orchestra pit shouted for him look upward. Covering his eyes against the glare of the spotlights, Mario found the sign and shrugged modestly. We knew he was pleased.

Afterward, we waited with our half-folded banner at the stage door, hoping to catch his attention. Mario would graciously sign our programs as his wife whisked him out of the winter weather into a waiting limo. I told him in my feeble Italian that we were students from Philadelphia who traveled everywhere to hear him sing. Subsequently, whenever he saw us outside the stage door with our banner, he greeted us with a jovial “gli studenti.”

So it was that many years later, in 1982, I decided to attend a master class that Mario, his wife Rina, and the soprano Marta Lantieri gave yearly to young singers at his villa in Lancenigo. I went as observer, but the trip was really a pilgrimage. It was time to tell my idol how much he meant to me. Class was held in the villa’s small music room. At the entrance we were greeted by his bronze bust, which is now in the museum at La Scala. In the room itself, beautiful portraits of Mario in all his roles graced the walls. A framed program of an early appearance in Andrea Chenier was signed by its composer, Umberto Giordano. It was inscribed “To the only Chenier.”

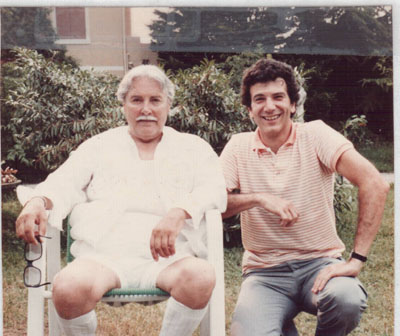

We all came alive when Mario entered. He always wore white, the only defense against the sweltering July heat. His hair and mustache were also white, framing a fashionable pair of wraparound sunglasses. Still handsome and charismatic at sixty-eight, his tremendous personality nevertheless seemed constricted by the ravages of the renal problems he had suffered over the past six or seven years. I was told he underwent dialysis several times weekly in the villa. My written notes at the time say that “he always appears distracted, as if looking for something that could contain his energy. Or perhaps he is still searching for some way to use again the magnificent instrument that age and illness have taken from him.”

I sat in his presence during the first days of classes, watching, writing, listening and bursting with the need to express the extent of my hero worship. I was biding my time, waiting for an appropriate moment to speak with him privately and remind him, if he remembered at all, of our banner madness many years earlier.

I created the opportunity several days later. I had spent an afternoon scouring the local Ricordi’s for del Monaco recordings and came across his autobiography. I thumbed through it and the first page I happened to stop at contained a paragraph, the last words of which were “il re dei tenori.” The full sentence read, “Another time, spectators in the balcony hung a banner thirty meters long on which they had written, `Bravo, Mario, il re dei tenori.’” I was overjoyed. Not only had he remembered the banner, he had included it in his autobiography.

Emboldened by the reference to our banner, I approached Mario the next day before class. I showed him the sentence and informed him that I and my friends were the ones who hung the banner. As he absorbed the information, I could see the tumblers of his memory falling into place. When they did, his first words were “gli studenti?” “Si, si,” I responded excitedly. He flashed his brilliant smile and shook my hand vigorously. He brought me to his wife Rina, who was confined to a wheelchair and out of earshot of our initial conversation. She smiled and said she also remembered the banner, saying it was the most unusual thing that ever happened to them in an opera house. It thrilled me to learn that they had taken notice.

But the most remarkable moment was yet to come. Several hours later, Signora del Monaco and Mario handed me a snapshot which they had taken from the wings of the Met’s stage. I was stunned. There it was, a photo of the banner with those big black letters I had painted on it hanging from the dress circle. Blow it up and you’d see me, Joe Curti, his late brother Dino, Ed Howell or Steve Vasso, hanging over the railing screaming mezzo-forte in tribute to another spectacular Mario performance. My own memory snapped back to one of those nights and, indeed, I remembered a flash bulb going off from the stage, a sudden recollection as vivid as if it happened that very instant.

Sadly, I never again saw the photograph. Signora del Monaco was sending it (I think) to publishers in Rio for the Brazilian publication of the autobiography. They hadn’t located it in time for inclusion in the Italian edition. I am told that it’s been published in some very large book on opera, which I’m still trying to track down. I would love to post its image in this article. Still, seeing it at that moment was enough, testimony that the relationship between the hero and worshiper goes both ways. Most of the time we fans never learn this. Happily, I did.

Mario’s voice was thrilling, quintessentially Italianate and possessed of that brilliant ring known as squillo. A voice either has it or it doesn’t. His did. His sound was so seamless from bottom to top that he seemed to have no technique. Yet despite his effortless vocal production, we felt that he flirted on the edge of danger — how could a voice of such enormous size and passion expect to reach the top of the tenor’s range without faltering, how could it sustain the punishing tessitura of Chenier or Otello? But with Mario, it always did.

Unlike many heroic tenors, his voice was not metallic or strident. Indeed, it had great beauty, which was most evident in his many lyrical passages. Yes, you critics who accused him of “shouting,” he often sang with finesse and a fluid lyrical line. Those sections thrilled me more than his dramatic declamations. An air check of a December ‘57 Met broadcast Carmen, his much overlooked London recordings of Mephistofole, La Gioconda and Tosca, to mention just a few, are testaments to his floating but still muscular leggerio.

The point is that he did modulate his vocalism. But his mezza-voce sounded like other tenors’ mezzo-forte. Were Mario a baseball player, he’d be a slugger and bat clean-up like Mickey or Hank and he’d thrill us with his spectacular home runs. Baseball fans would never criticize Mantle or Aaron because their dingers were too long, or because they didn’t hit enough singles or doubles; yet critics always faulted del Monaco for the size of his voice. It was what it was. If you want another kind of voice, go to DiStefano or Bjoerling — they bat second and third in the operatic line-up.

Mario did hit his share of doubles, however, and we thought they were more beautiful for their restraint because we knew he could pop them over the fence at will. Most importantly, his voice reached the bleachers — sorry, the balcony of the Met. We always heard him in the cheap seats. Not a bad attribute for an opera singer, and one that’s noticeably absent in this era of mostly polite, sanitized and lustless singers.

Mario was an electrifying stage personality. The full package couldn’t be appreciated on records, which merely archive his vocalism; and of those, the pirated live performances are preferable over the more sterile studio recordings. There are exceptions, of course, notably the above mentioned Tosca with Tebaldi and London, the exciting La Gioconda with Cerquetti and the great, also missed, Ettore Bastianni, the von Karajan Otello. A Met broadcast Otello in March of ‘58 with de los Angeles and Warren was extraordinary, as was an earlier one conducted by Fritz Steidry, in which the tempi practically came to a screeching halt. Yet Mario used it to his advantage — Otello appeared more noble and measured at first, making his inevitable disintegration all the more startling. These are the adjustments a good actor makes on stage, inspired by the presence of an audience as opposed to studio engineers.

Nothing need be said about his Otello. Others sing Otello, he was Otello, a role that must have obsessed him since he sang it 426 times. His was such a visceral portrayal that even his few moments of serenity were ominous and nerve wracking. His Chenier was intense and aristocratic and I’d follow his Samson into the jaws of hell. He sang Canio like no one else, but it was a role I didn’t buy him in. How could Nedda prefer any Silvio to this hunk? (Well, okay, maybe if someone like Sherrill Milnes were singing Silvio.) I wish I had seen his Cavaradossi, Turridu, or Calaf. I’d even settle for a good live recording of any of them, but my search thus far has been fruitless.

One final note. My mother had been staying with us in Los Angeles when my friend Bob Prag, the classical guru at Tower Records in Los Angeles, called to tell me that Mario had died. She had lived all my adolescent years with his recordings blaring from my room and watched daily my growing affection and fanaticism for his singing. She said that Mario had waited for me to visit him before dying. Sentimental, romantic, preposterous, even, but I like to believe it was true.

Ciao, Mario and thank you again. I’m still listening. And so is my son. His voice isn’t raspy anymore. But he isn’t a del Monaco either. We’ll never see one again I’m afraid.