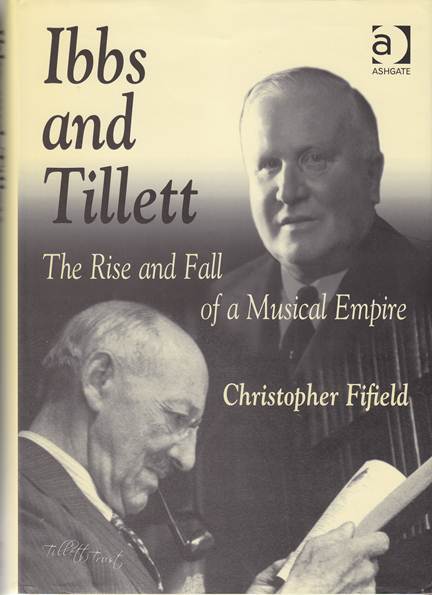

The Rise and Fall of a musical Empire

By Christopher Fifield

www.ashgate.com 678 pp

Ibbs and Tillett

The Rise and Fall of a musical Empire

By Christopher Fifield

www.ashgate.com 678 pp

What seems to be at first sight a great book on a most illustrious music agency turns out to be somewhat disappointing for the vocal buff. The initial owners were not interested in opera and when the young widow of the surviving partner took over in 1948 opera remained anathema to her organisation. Therefore opera lovers will recognize a lot of names of British operatic singers but only in their capacity and indeed main professional activity as oratorio or concert singers. And to be honest, Britain gave us a lot of good honest singers but very few talented with genius. Most Brits who made it in opera (McCormack for a time, Eva Turner, Lionel Cecil, Alfred Piccaver, Margaret Price, Gwyneth Jones, Kiri Te Kanawa etc) are barely mentioned if at all. So the interest of this long and even exhaustingly researched book is limited for those mainly interested in opera.

We get an awful amount of details on the number of artists and contracts while nevertheless it remains unclear how Ibbs and Tillett functioned in reality. Maybe the author presumed that most readers would be familiar with a once legendary name in British music life but readers in the colonies like the US or those who had the bad luck to be born and are still living on the European continent don’t get a clue during the first part of the book. The clouds disappear and the sky becomes far more interestingly when the author interviews people with very vivid memories of the last forty years. Maybe this reviewer isn’t a very sharp guy but it only became clear to me at that moment that Ibbs and Tillett was not a real agency, but more of a clearing house. It connected singers on its lists with choral societies and music clubs on other lists. Ibbs and Tillett were interested in getting performances before the public and not in promoting individual careers of singers. The percentages it took on fees were modest and as a consequence the directors of the firm didn’t become rich on the backs of performers. As often in music business their staff –mostly people passionately interested in good music – were woefully underpaid. As a clearing house Ibbs and Tillett was divided into sections: oratorio, vocal concerts, instrumental concerts etc. The different sections often employed the same artists but hadn’t a clue someone two doors further was engaging the same musician for another activity. It makes fascinating reading indeed to learn how Ibss and Tillett worked in reality for decades: in a hopelessly outdated manner which somewhat resembles large parts of nowadays England where the foreign visitor sometimes has the impression he has returned to the fifties and sixties. At Ibbs and Tillett someone took a call from a music society, jotted down the wishes and then went to look at the performers’ lists and puzzled out who could sing or play the required music and then pencilled down a name of the soloist. Then he or she started to contact the singer or instrumentalist and when there were no objections penned down the name. Most business was done in writing and with as few calls as possible as that was thought to be expensive. Overseas mail and not air mail was to be preferred; even in business with the colonies. And overseas calls (granted, not cheap) were off limits, even in the seventies. As a result this meant an immense amount of documentary evidence was available for this book and some of it is a small treasure trove for the admirers of Kathleen Ferrier who receives a whole chapter in her own right. The lady had strong opinions and much of it would have been lost if the firm had handled problems by phone.

This archaic system was fine from the beginning of the century till the early sixties but then the rot started to enter. Emmie Tillett still refused to accept operatic bookings though it was clear that was were the money was as one got a commission for a whole series of performances with the same pains it took to book one single concert. Some younger men made their entrance, were groomed as inheritors and then got unceremoniously dumped as they tried to change Edwardian procedures. Due to better and cheaper communications and far better transport music business became far more international while at the same time environmental pollution known as rock attracted youngsters all over the world leaving classical music gasping for breath. Classical artists wanted more and more personal handling of their affairs and demanded services of one single agent who would handle all their engagements, notwithstanding if the fare was opera, oratorio or a song recital. Talented people who had left Ibbs and Tillett saw those needs and started modern and performing agencies; often specializing in a few clients instead of the dozens of tenors, sopranos etc. I&T employed. By the beginnings of the eighties it was clear for everyone in the business that Ibbs and Tillett were down and no removal to cheaper premises, no belated acceptance of operatic performances could save it and it disappeared in a whiff of scandal in 1990.

Jan Neckers