(KF and her second husband + Elisabeth Delius)

(KF and her second husband + Elisabeth Delius)Sunday, July 12, 2020, is the 125th anniversary of the birth of Kirsten Flagstad, one of the most astonishing singers to ever appear in opera and concerts. During her career she enchanted millions of people, and today her recordings are a touchstone that proves truly great singing can convey astounding depths of emotion while still remaining beautiful—even in the most strenuous roles written by Richard Wagner. But The Flagstad of Legend could very easily have never happened. Except for a series of fortuitous circumstances it is quite possible that Kirsten Flagstad would have always remained what she was before her Metropolitan Opera debut—a well respected, hard working soprano virtually unknown outside of Scandinavia. The confluence of events that brought her to the Met—and into operatic legend—is a story that is as riveting as it was unlikely.

Consider…

If Flagstad had not very gradually ended the retirement she enjoyed after marrying her second husband, Henry Johansen, in 1930…

If Johansen had not encouraged her to do whatever she wished about singing again, eventually becoming a constant source encouraging her to take chances she probably would not have taken on her own…

If Ivar Andresen had not become ill and been replaced as King Mark by Alexander Kipnis at her last three Oslo performances of Tristan...

If soprano Ellen Gulbransen had not written to Winifred Wagner about auditioning Flagstad for the Bayreuth Festival after Flagstad thought it was pointless and declined to do so herself…

If Frieda Leider had not wanted out of her 1934-35 contract at the Met…

If Anny Konetzni had been able to give the Met more than just a few weeks at the end of 1934, instead of leaving the Met desperate for someone who could sing the heavy Wagnerian repertoire for the rest of the season…

If Flagstad’s husband had not told her to go to the St. Moritz audition for the Met and promised to go with her to New York if she was hired…

If Swiss soprano Elisabeth Delius had not been considered “thirty pounds too heavy to sing at the Met”….

…Kirsten Flagstad might very well have not have made her Metropolitan Opera (and American) debut on February 2, 1935 and become an instant star, twenty-one years after making her operatic debut and six months shy of turning 40 years old.

(KF and her second husband + Elisabeth Delius)

(KF and her second husband + Elisabeth Delius)

IT STARTED WITH LOHENGRIN

Flagstad’s Wagner career began with Lohengrin. For her tenth birthday her parents had given her the score of the opera and she had taught herself the role of Elsa—in German. This meant she had to relearn the part in Norwegian when she eventually sang it on stage, a reversal of what she later would have to do at the Met when she had to relearn several roles in German after only performing them in Norwegian or Swedish. On June 14, 1929 she sang her first Wagner opera in public—Lohengrin at the National Theater in Oslo. In the audience that evening was the wealthy Norwegian businessman Henry Johansen. He was one of the sponsors of the season and at a party at his Grand Hotel after the performance, he and Flagstad were introduced. When he invited everyone to continue the party at his home, Flagstad went along.

(KF as Elsa)

(KF as Elsa)

“I was in a daze that night. I can’t explain it otherwise,” she later recalled. “Something unusual, quite trivial in itself, happened. Mr. Johansen had a chair in that house that no one occupied but himself. He strictly forbade everyone else to use it. Some of my friends knew about this. Naturally I did not. Well, the moment we arrived I fell into this very chair and made myself quite comfortable. Mr. Johansen said nothing. He let me sit there and even came over, sat on the arm of the chair and spoke to me.”

He invited her to dinner the next evening and she accepted. The next three days they had dinner, went to the opera, and saw mutual friends: “On the third day he proposed to me. Still in a daze, I accepted.” Johansen always insisted he had fallen in love with Flagstad the minute the new Elsa came out on the balcony in Act Two. “At least that’s what he said,” Flagstad commented. “I don’t vouch for it. Men are all romantics at heart. I have reason to believe him, though.” Johansen was twelve years older than her, a widower with four children. Flagstad had been separated from her husband, Sigurd Hall, for some time and had a daughter, Else. After initially agreeing to a divorce, Hall then changed his mind, which meant Flagstad and Johansen had to wait until May 31, 1930 before finally marrying at the Norwegian consulate in Antwerp, Belgium.

Johansen expected her to give up her career and Flagstad was fine with that. She had been singing on stage with few interruptions since her debut on December 12, 1913 when she appeared in the role of Nuri in d’Albert’s Tiefland at the Oslo National Theater and, as she later recalled, with her marriage to Johansen, “I didn’t have to earn my own money anymore and I thought it was time to give it up, anyway, except perhaps to sing at an occasional concert. I was fed up with singing, I tell you. It had been hard, unrelenting work…I felt I had earned a long rest.”

The 1930 Spring Season at the Stora Teatern in Göteborg, Sweden, would be her last engagement and it brought her two new roles: Eva in Die Meistersinger (which she adored and, in later years, rued she had been unable to sing very often) and Anita in Krenek’s opera Jonny spielt auf (which she loathed). The Krenek opera was a modern, jazz-infused score that was only three years old. The only time it drew a full house that season was Flagstad’s farewell performance when she was deluged with flowers, then presented with a silver bowl engraved with the names of all of her colleagues. At the conclusion of his speech, the company manager said, “If you should ever change your mind, you will always be welcome at the Stora Teatern in Göteborg.”

On their wedding trip the new couple motored through Germany, then spent some time in Vienna where Flagstad heard Tristan und Isolde for the first time. She was tired and wanted to leave after the first act but Johansen wanted to stay, so she dozed through the last two acts. After the performance Johansen joked with her, “This is something you could never sing, young lady.” Flagstad agreed.

Back home in Norway she happily settled into her new role of Mrs. Henry Johansen, mistress of a large home in Oslo with numerous servants. But in September she got a call from the Oslo Philharmonic asking her to participate in a concert conducted by Issay Dobrowen. After consulting with her husband she agreed—and discovered that not singing for several months meant considerable work getting her voice back into shape. She decided that even if she was not going to sing in public except on very rare occasions she was going to keep her voice in shape from then on.

In March 1931 the call came again for concerts in Bergen and in Oslo and then in June, for performances as Verdi’s Aida (a role she had enjoyed doing before) at the National Theater in Oslo. There were other occasional concerts and then in late November she got a frantic phone call from Göteborg. The soprano who had replaced her at the Stora Teatern had become quite ill. Could Flagstad please bail out the company by learning the role of Dorota in Jaromir Weinberger’s Schwanda der Dudelsackpfeifer (Schwanda the Bagpipe Player) in time for the opening in eight days? She discussed it with her husband and, with his blessing, accepted the challenge. And then something changed. “I found out soon enough that he [Johansen] was thrilled every time I sang,” she later recalled. “In one way he didn’t want me to sing, for my own sake and for his, too, because he wanted me constantly with him. But when I did sing he was the proudest man alive, as if he had himself created my voice.” Johansen, in fact, became her biggest fan and a constant voice encouraging her to take new opportunities as they arose and which she otherwise would probably have let slip past.

(Aida)

(Aida)  (Dorota)

(Dorota)

During the Schwanda performances in December the general manager told Flagstad that if she would sing the title role in Handel’s Rodelinda, they would give it in two months, in February 1932. She accepted, and after the premiere Johansen said to her —very excited—“After hearing you tonight, I’m convinced that you can sing Isolde!” He was prophetic. A month after Rodelinda, the Norwegian Opera Association asked her to sing Isolde in June when they planned to give the first performances of Wagner’s opera ever given in Norway. She turned them down flat. But when they explained the first five performances would be sung by the famous Nanny Larsen-Todsen, with Flagstad taking over for the last five, she agreed, even though by that time she would have only six weeks to learn the role.

THE FIRST ISOLDE

Click here to listen to her singing Isolde's Liebestod

Click here to listen to her singing Isolde's Liebestod

Flagstad’s mother, Maja, had coached most of the top singers in Norway but, for some reason, mother and daughter had never worked together until then. It would be the first time Flagstad had sung a role in German, and she was fully aware of how difficult Isolde was: “Isolde is a severe test for the voice: either it can be completely destroyed; or it can grow, as mine did.” She worked with her mother several hours a day and after a while she made a startling discovery. All of her dresses were splitting down the seams. She was not gaining weight; singing Wagner’s long, sustained phrases was developing her back muscles like a swimmer, and increasing her lung capacity. Maja was relentless and unmerciful. “In the middle of a passage she would stop, look at me sternly, and say, ‘Kirsten, there is a sixteenth-note rest here. It has not been placed here as a decoration—remember that.’” Maja was also amazed at how her daughter’s voice was growing in size.

Flagstad’s first Isolde was on June 29, 1932. No one expected her to own the role like the experienced Larsen-Todsen did. But, as the Aftensposten’s critic wrote, “It fulfilled every expectation. But virtue of her youth and brilliant vocal art, Kirsten Flagstad triumphed as Isolde. Her interpretation of the role confirmed that we have in her a Wagnerian singer for whom we may cherish the greatest expectations. If the lady wishes, it will not be long before she can appear both at Bayreuth and at the Metropolitan!”

Prophetic words, indeed, even if Flagstad herself did not seem to believe them, as evidenced to her reaction when the famous soprano Ellen Gulbransen came to her dressing room after a performance. In addition to singing throughout Europe, Gulbransen had been a leading soprano at Bayreuth between 1896 and 1914. She told Flagstad flat out that her voice was meant for Wagner and it was a pity she was “burying it” at home and not singing abroad, adding Flagstad should try to go to Bayreuth and learn the proper style of performing Wagner.

Flagstad laughed, thanked her for her advice, and explained, “I’m sure I haven’t the slightest chance of singing at the Bayreuth Festival where they engage only the very best. Besides, I am not considering any career abroad as a singer. I am happily married, and if I continue to sing, I will be fully satisfied to sing here at home.”

Gulbransen promptly took matters into her own hands and wrote to Winifred Wagner who replied that Flagstad would be welcome to audition in July when singers for the following year’s festival would be selected. Henry Johansen urged her to go, pointing out it would be a great educational experience if nothing else, so “with trembling knees” Flagstad went down to Bayreuth on her own. Winifred Wagner was gracious and introduced her to Heinz Tietjen who was, as Flagstad later put it, “the head of everything,” and then told Flagstad to come see her after the audition in the Festspielhaus.

In Oslo, Tristan had been performed with cuts, including one in Isolde’s Narrative, which is what Flagstad was using for her Bayreuth audition. She had gone over the music with the accompanist, Professor Carl Kittel, one of the festival’s head coaches, so he knew there was a section in the middle she didn’t know. But during the actual audition he forgot and played the cut passage. Flagstad was forced to stop and explain to everyone she did not know that part. Once she finished the Act One excerpt she wanted to sing the Liebestod but was told, “No, no, that’s sufficient.” She assumed that was the end of any association with Bayreuth, but Winifred Wagner set her straight. They had been impressed she chose the Narrative for her audition, no one else had done that in Frau Wagner’s experience, and they wanted to engage her for the next two years of the Festival, in 1933 and 1934. Unfortunately major roles had already been assigned, but they could offer her small roles that would give her the opportunity to pick up the Bayreuth tradition. “You need the polish of language and the grand manner and style,” she was told. Flagstad was hired to do the Third Norn in Götterdämmerung and Ortlinde in Walküre and to understudy Eva in Meistersinger and Sieglinde in Walküre for appearances in July and August 1933.

ENTER ALEXANDER KIPNIS

Back in Oslo she had three more performances of Isolde to sing in August. To her surprise, her voice seemed to have grown since her previous Isoldes just a few weeks before. “It had not only grown but it responded to my wishes with much more ease. Moreover, it had deepened to a darker color.” She also had a new King Mark, Alexander Kipnis, who was stepping in for an indisposed Ivar Andresen. Kipnis listened in amazement to Flagstad’s first act and then went to her dressing room after the second act to tell her how impressed he was. First he spoke to her in German, but she was shy about her German and responded pretty much in monosyllables. Then he switched to English which she knew fairly well, but was even shyer about using. “Luckily, Kipnis didn’t tell anyone abroad what an idiot the Norwegian Isolde had been,” Flagstad recalled. “To the contrary, he recommended me to opera managers in both Europe and America. And I was soon to discover what it meant to be recommended by Kipnis. He opened up the way for me.”

(Kipnis as Marke)

(Kipnis as Marke)

The American critic Oscar Thompson heard one of those August Tristan performances and gave Flagstad her first reviews in the US, in the New York Post (October 8) and then in Musical America (October 25) where he wrote: “If not of heroic figure, she brought to Isolde much of womanly charm, united with an exceptionally smooth and musical delivery of the music, which was highly impressive and convincing in its wide gamut of emotion, from the first nuanced utterances of the opening scene to the final exaltations of the Liebestod.”

In addition to working on her Bayreuth roles, Flagstad took the advice given to her by Heinz Tietjen after her audition, and began to study the Ring Brünnhildes, starting with Siegfried. “I realized that if I could manage the Brünnhildes I would probably be invited back to Bayreuth every summer. But the thought did not make me any more ambitious, really. After my Bayreuth audition Dr. Tietjen had asked me, ‘Do you want to come to Berlin and the Staatsoper [of which he was also head] and get into the repertory and sing all these roles?’ I had said no. He was astonished and wanted to know my reasons. I said, ‘Why should I? I’m happily married and I like staying in Oslo.’”

When she got to Bayreuth in June 1933 she dived headfirst into the rehearsals, soaking up everything she could. She recalled, “the performances went marvelously, my two small roles and all. They sharpened my appetite for more. When it was over I was invited to come back the following year and do Gutrune in Götterdämmerung and Sieglinde in Walküre. Dr. Tietjen repeated his offer to have me come down to Berlin, adding, ‘If you can come to Berlin in May next year, I will coach you for Sieglinde.’”

(Heinz Tietjen)

One of the highlights of that year’s Bayreuth Festival for Flagstad occurred on August 4, when she sang the soprano part in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, conducted by Richard Strauss. The concert was in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of Richard Wagner’s death, and the third anniversary of Siegfried Wagner’s death. Ironically, in the letter Strauss wrote to Flagstad years later inviting her to give the world premiere of his Four Last Songs, it is obvious he did not remember they had once worked together. But after the Beethoven performance Bayreuth’s chorus master, Hugo Rudel, came up to her, bowed, and said, “I have heard, coached, and conducted more performances of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony than I can count, but I was to be in my late seventies before I was privileged to hear a soprano soloist like you, Miss Flagstad.”

Though she had a few concerts that winter, Flagstad worked steadily on her new Bayreuth roles, looking forward to going to Berlin to coach with Tietjen. This assumed even greater importance when she was invited to sing Sieglinde in Brussels on May 24 shortly before she was to do the role at Bayreuth—thanks to glowing praise from Alexander Kipnis. So she went to Berlin eager to polish the role, but found Tietjen was involved with a Strauss festival and, despite repeated promises on his part, he never managed to actually see her. Having enjoyed a week of Strauss operas, Flagstad went to Brussels where she made a disconcerting discovery. The performances were being given by a German opera company. Her colleagues were German and all very familiar with the Wagner tradition, something she had been specifically hoping to learn from Tietjen.

The rehearsal was a disaster for her. Though she knew the role cold she was suddenly terror-stricken and forgot all the stage directions. The Hunding whispered to her, “Listen, how often have you sung Sieglinde, anyway? Something’s wrong here. You have either sung it too often or not at all. Which is it?” Flagstad replied, “I’ll tell you after the performance, if you don’t mind.” Fortunately at the performance her confidence had returned and things went extremely well. When she confessed to the Hunding it had been her very first Sieglinde he didn’t believe her.

AMERICA BECKONS

At Bayreuth Tietjen “deplored” the fact he had been unable to see her in Berlin. She apparently was indisposed for her only Sieglinde performance but her Gutrune caught the eye of the critics, one of whom wrote, “With her excellent stage appearance and vivid acting, Kirsten Flagstad managed to liberate Gutrune from the neutral significance she is often given in this drama.” It was during that 1934 festival that everything changed for her.

Fritz Reiner had been impressed by Oscar Thompson’s review of her Oslo Isolde in Musical America and invited her to sing three performances of the role in Philadelphia in October. She was under contract in Göteborg from September to December, singing Fidelio and Tannhäuser, but the management of the Stora Teatern refused her request to shift her dates a little so she could accept Reiner’s offer, so she had to turn him down.

Then, a week before the Bayreuth Festival ended she got a cable from the Metropolitan’s European agent, Eric Simon: “Are you interested in singing dramatic Wagnerian parts like Isolde and Brünnhilde at Metropolitan next season? Stop. Keep this to yourself until later. Letter follows. Stop. If interested, please answer by telegram. Eric Simon.” She was stunned and not at all sure what she ought to do, so she called her husband who was back home in Oslo and asked his advice. He was delighted for her and very proud of the opportunity that had appeared just out of the blue. “But what of you if something comes of this?” she asked. “I’ll come with you,” he replied. “Say that you are interested.”

When the letter from Eric Simon arrived it instructed her to go to St. Moritz in Switzerland where she was to sing for Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the Met’s general manager, and the conductor Artur Bodanzky who was in charge of the company’s German wing. She was to be prepared to sing the three Brünnhildes, as well as Isolde and Fidelio. She had six days to prepare, while she sang her final performances at Bayreuth. She had started studying the Siegfried Brünnhilde but knew practically nothing of the Götterdämmerung, so she went to see her Bayreuth coach, Carl Kittel, to ask his advice—which was tricky since she could not explain the circumstances. Kittel said she should learn Götterdämmerung’s Immolation Scene so she could do it from memory. To further complicate matters, Flagstad had not sung Isolde in two years and in Bayreuth, of all places, she could not buy a copy of the Tristan score. “We’re not giving Tristan this year,” was the answer she kept getting. There were also no scores for Fidelio which she only knew in Norwegian.

When she thought about what she was being asked to do and the difficulties she was having trying to prepare, she said to herself, “Well, this looks pretty hopeless, but, come what may, I’ll go down to Switzerland. If they don’t want me it’s all right too.”

She sang her last Gutrune on August 20 and left the next day for St. Moritz, still very unsure she was doing the right thing. “My determination to give up my career after my marriage had completely collapsed. The quiet home life I had so looked forward to had lasted less than three months. Then I had slid into work again—and had liked it. After all, I was a singer! I was torn with conflicting emotions.”

(Carl Kittel) (Otto Kahn)

This was not, actually, the first time the Metropolitan Opera had approached her. In 1929 Otto Kahn had heard her do Tosca in Göteborg and given her his card, but she had put it aside since his name meant nothing to her. The newspapers got a hold of the story that a powerful director of the Metropolitan Opera had hired her and asked her about it. She immediately quashed the idea. But Kahn had written to Gatti-Casazza about her and Gatti asked Eric Simon to look into the situation. A few months later Flagstad received a letter from him asking for extracts from reviews, translated into English, as well as stage portraits, to be sent to New York. Flagstad did not put the request together with having met Otto Kahn after Tosca and could not understand why the Met was contacting her. Getting together reviews, having them translated, collecting photographs was a lot of bother, so she did not reply to the letter. Three weeks later a second request arrived. Not wanting to seem ungracious, Flagstad obliged, though she was annoyed at being put to all the trouble since it seemed absurd the Met would actually be interested in her. As it happened, she heard nothing back.

When she arrived in St. Moritz she was met by Eric Simon. “I reminded him that he had written me several years before. He had no recollection of our correspondence.” She asked how did the Met get her name. “Alexander Kipnis has been talking about you,” he replied. He also explained to her that the reason for all the secrecy was that Frida Leider—ironically her Brünnhilde at Bayreuth—wanted out of her contract and while Gatti did not want to keep singers who were unhappy, the Met needed someone to sing her roles after Anny Konetzni left in December.

LEIDER’S DILEMMA

Actually, Leider had been sending the Met a steady stream of letters about the difficulty her Met contact was causing her. In one she said her doctor had warned her that traveling on the Atlantic Ocean for several days in winter would be terrible for her arthritis. Though New York audiences and critics had greeted her warmly, she was not happy at being pigeonholed as a Wagner singer. She had sung two seasons at the Met, 28 performances, all Wagner except at one concert when she had sung Alceste’s “Divinités du Styx.” By contrast her repertoire for her four seasons at the Chicago Civic Opera had included Verdi, Strauss, Mozart, and Rachel in La Juive, in addition to Wagner. Covent Garden, and her home theater, the Berlin Staatsoper, also gave her a wide repertoire.

Then there was the developing political situation in Germany. Hermann Göring had appointed her, Heinrich Schlusnus, Rudolf Bockelmann, Helge Roswaenge, Maria Müller, and others to the “Prussian Chamber of Singers” i.e. Kammersängerin, with long term contracts and honorary salaries. Though the Nuremberg Laws were not enacted until the following year, Leider and her husband, the Berlin Staatsoper’s concert master Rudolf Deman (who was Jewish), were under increasing pressure by the Nazi regime. Being so far from him (and from her elderly mother) at a time of such uncertainty was clearly something she would rather avoid—especially if she were only going to be allowed to sing Wagner at the Met. But, in the meantime, the Met needed to replace her.

(Leider) (Hermann Weigert and Varnay)

Once Flagstad was in St. Moritz, she went to her hotel to rest. She had been on the train since five that morning and was exhausted. But Hermann Weigert (later the husband of Astrid Varnay) tracked her down and wanted to go through what she would sing the next day since he would be accompanying her. There was no piano in her room so they went to his pension where there was a piano in the salon. Flagstad was always shy about singing in front of people unless it was a performance, and when people began settling in to listen to what they clearly assumed was a bit of entertainment, she became even more ill at ease.

Weigert asked about her repertoire and grew more and more annoyed as she explained the difficulty she had had trying to find scores, and the fact she was studying some roles but didn’t yet know them. When she offered to sing Sieglinde he cut her short. “Nobody wants to hear you in that that! Can you sing [Walküre’s] Todesverkündigung scene?” Flagstad replied she could, but only using the score. Weigert became increasingly annoyed when it turned out she didn’t know Götterdämmerung by heart and finally snapped, “Is there anything at all that you know by heart?”

“Yes, Tristan!”

By then Flagstad was getting annoyed, too. She was doing her best to accommodate the Met, they had asked her, after all, and Weigert was making no bones about the fact he thought she was a lost cause. Finally Weigert asked, “Do you know ‘Ho-jo-to-ho’ from Die Walküre?”

Flagstad said she did.

“By heart?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Sing it, then!”

Flagstad was fed up at the way he was treating her. She let loose all her fury and sang the hell out of the war cry. He nearly fell off of his seat and, in a complete about face said, ‘You’re going to be engaged right away! Don’t doubt it for a minute.’” Though she wasn't so sure abou getting hired, Flagstad, as she later put it, “did consider it a triumph that I’d been able to convince Mr. Weigert that I had something to offer.”

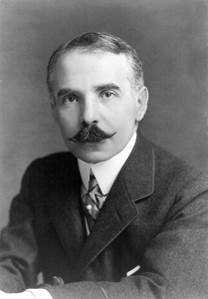

THE FATEFUL AUDITION

The next day, August 22, was hot and sultry, without a breath of a cooling breeze. The audition was held at Suvretta House where the Met’s general manager, Giulio Gatti-Casazza, vacationed every year in St. Moritz. Before the 11 o’clock audition itself Flagstad and the other singer who was involved, Swiss soprano Elisabeth Delius, had a brief rehearsal with Hermann Weigert. Delius was an experienced dramatic soprano who knew all the big Wagner roles in both German and Italian. Born in Mülhausen in 1890, she had made her debut in Augsburg during the 1919-20 season as Leonore in Fidelio before moving on to Chemnitz and Prague. She also sang in Dresden, Basel, Bern, and Zurich. She had an enormous repertoire stretching from Donna Anna in Don Giovanni to Marie in Wozzeck. Flagstad thought Delius seemed very poised and assured.

They were to perform in a large room filled with heavily upholstered furniture, a thick carpet, and massive velvet drapes, all of which would muffle a singer’s voice. Delius was dressed in an evening gown, Flagstad wore a simple dress and matching jacket. When she heard Delius sing Flagstad decided she didn’t stand a chance. Delius possessed what Flagstad described as “a gorgeous voice, beside her I was nothing at all.”

But while Delius was singing “Dich, teure Halle” Flagstad noticed a Swiss fifty-centime piece on the floor and picked it up. “I’m not at all superstitious; still I like to feel that the little coin has brought me good fortune. I had it set in my bracelet later and treasure it.”

Gatti came into the room along with his second wife, the former dancer Rosina Galli, conductor Artur Bodanzky, and Eric Simon. Rather than hearing the two sopranos separately, they were auditioned together, in front of each other. One would be asked to sing a number, then the other had to repeat it, allowing the listeners to instantly compare them. Bodanzky began by asking Flagstad what she wanted to sing but refused her offers to sing Sieglinde or Elisabeth. “We don’t need you for that, Madame Flagstad. What else do you know?”

Eventually both singers were asked to sing the Todesverkündigung scene from Walküre, and Leonore’s aria from Fidelio. Bodanzky asked Flagstad to do Isolde’s Narrative. She explained about being unable to find the score at Bayreuth but volunteered to sing the Liebestod. “No, everyone can sing the Liebestod. Sing Brünnhildes Ho-jo-to-ho.” Flagstad let fly with everything she had.

“You sang flat. Do it again,” Bodanzky said. Flagstad did.

“Once more,” Bodanzky ordered. She sang it a third time.

“That’s right,” Bodanzky said, and asked Delius to sing it, but not to repeat it.

“Now let’s hear your Elisabeth,” Bodanzky said to Flagstad who thought he seemed genuinely interested.

Delius was asked to sing the Immolation Scene through entirely. Then it was Flagstad’s turn but Bodanzky said, “But don’t sing the whole thing—start towards the end.”

“By then I was feeling quite happy over the way the audition was going,” she remembered. “Gatti appeared to be pleased with me. Mr. Bodanzky, though, looked very serious and forbidding.”

(Delius)

(Delius)

(Gatti) (Bodanzky)

With the Götterdämmerung excerpt the audition was over. The two sopranos were told to wait in the hall while Gatti, Bodanzky, and Simon conferred. While they waited—for 45 minutes—Delius turned to Flagstad and said, “They’re going to take you,” but Flagstad wasn’t at all so sure. When the men emerged from the room, Gatti looked at Flagstad and said, “Auf Wiedersehn,” before disappearing. Eric Simon invited the two women to lunch and when Delius went to change from her evening gown into something more appropriate, Simon said, “Now I can say it! You will be engaged by the Metropolitan, Madame Flagstad. The contract will reach you in less than two weeks. Before that time you must not let it be known that you have been engaged.”

When Delius rejoined them she said, “Well, Mr. Simon, I’ll tell you what’s happened before you tell me. They’ve engaged Madame Flagstad. Isn’t that so?”

Simon confirmed her suspicions, then added, “They liked you very much, too, but—well, you know yourself—you are much too heavy. You don’t mind my being frank do you? You’d have to take off something like thirty pounds before you came to the Metropolitan.”

Flagstad described Delius as “one of those persons with very short necks, packed thick.” When Flagstad tried to convey how badly she felt for Delius, the other soprano insisted that she didn’t mind at all the way things had turned out. “She was one of the best losers I’ve ever met,” Flagstad said.

Later that afternoon she met again with Bodanzky. “He gave me a list of the parts I should study. The three Brünnhildes, Isolde unabridged, Leonore in Fidelio; and the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss. ‘Find yourself a good coach and learn them as fast as you can, then come to America. The quicker the better.’” Flagstad explained she was committed to sing Tannhäuser and Fidelio in Göteborg until the end of December.

“Do you suppose you can find time to go to Prague and study these things with Professor Szell?” Bodanzky asked.

Flagstad said she’d try. “His parting words to me were: ‘Come to New York as soon as you know these roles. And above all, do not go and get fat! Your slender, youthful figure is not the least reason you were preferred.’”

When her contract arrived two weeks later it stipulated she should also be prepared to sing Elsa in Lohengrin, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, and Sieglinde in Walküre. Everything, of course, in German. She was engaged for nine weeks, from January 28th to March 31st, 1935. As an indication of how little the Met thought of her, she was paid by the week ($550), not the performance (some leading singers were being paid twice that per performance), and there was no option to renew the contract—something the Met rued many, many times in years to come!

It was an extraordinary gamble. She had never sung any of the Brünnhildes or the Marschallin. Her performances of Elsa had been in Norwegian and she was scheduled to sing her first Elisabeths and Leonores in Swedish. There were a number of sopranos at that time who could perform the same difficult repertory. However, no one, before or since, has dared to attempt to learn so much in so short a time. The Met was either very confident or—more likely—simply desperate.

Flagstad tried to get released from her Göteborg contract, pleading that she had done many favors for the company before, and she badly needed the time to learn her new role. “All they said was, ‘Oh, you can do it, anyway. We know your ability.’ They refused to release me.”

WORKING WITH SZELL

(Szell and composer Jaroslav Křička in pre-WWII Prague)

(Szell and composer Jaroslav Křička in pre-WWII Prague)

After singing her Tannhäusers, Flagstad went to Prague to work with George Szell for ten days. It was not a pleasant experience. “Professor Szell treated me like a beginner,” she said. “He bullied me and scared me nearly out of my wits with his outbursts of rage over the most minor mistakes….After ten days of inhuman drudgery, Professor Szell declared that I didn’t need to worry about my roles; that I knew them cold. He said he would personally write Artur Bodanzky and tell him that. For the first time he smiled.”

While in Prague she did manage to hear some opera, but no Wagner: Les Huguenots, Hilde Konetzni and Rose Pauly in Don Carlos and Pauly in Fidelio, as well. Flagstad’s own performances of Fidelio when she returned to Göteborg were a triumph. Friends and fans all wanted to hear her once again before she went to New York and the performances were sold out.

Of course the Scandinavia press was filled with the news that a local singer had been chosen to sing at the famous Metropolitan Opera in New York City. One interviewer, for the Aftenposten, expressed concern that singing dramatic soprano roles might cause her to lose the unique color of her voice. Flagstad agreed that her voice was lyric but that it had started to change when she sang Isolde. Simply singing Wagner did not necessarily mean the essential ring or tonal color of a voice must change. And as an example she pointed out that Frida Leider, her Bayreuth Brünnhilde, “proved that she still had kept hers. She sang beautifully.”

Flagstad and her husband sailed from Göteborg on December 29 on the Drottningholm. A journalist asked her if she was looking forward to performing at the Met. “I look forward most to coming home when the engagement is over,” she replied. When the interview was published the headline read: “Kirsten is homesick before she leaves.”

(SS Drottingholm)

What neither Flagstad nor her husband knew, of course, was that the future of the Metropolitan Opera itself was in considerable doubt. Between 1910 and 1928, General Manager Gatti-Casazza had actually made money producing opera, building up a surplus of a million dollars. But with the stock market crash of 1929 and the resulting Great Depression, the Met’s financial cushion had vanished. Attendance was down and there were fewer subscribers. There were extensive talks with the New York Philharmonic about merging the two institutions but nothing came of them. In fact, it was not until April 28, 1934 that Lucrezia Bori, the popular Spanish soprano who was head of the committee conducting a drive to raise an opera guarantee fund, could announce that another season of the Metropolitan Opera was assured. Subscribers were notified the next day of the fourteen-week 1934-35 season, the shortest in more than thirty years.

A further complication, hanging over everything, was the as yet unannounced retirement of Gatti-Casazza himself; this would be his final season. Throughout the season, the question of money and the succession would be inextricably mixed. Gatti returned from Italy on October 26 and resigned on November 9. He told a friend that he was looking forward to going to Italy to live in his villa on the edge of the Lago Maggiore and “listen to the blackbirds sing.”

In early December, Gatti’s right-hand man, Assistant Manager Edward Ziegler wrote a colleague in London and described conditions at the Met: “With us things are desperate and we are fighting for our existence. Our future is in the lap of the gods.” The season opened December 22 with a brilliantly cast Aida: Elisabeth Rethberg, Maria Olszewska, Giovanni Martinelli, Lawrence Tibbett, and Ezio Pinza, conducted by Ettore Panizza who was making his debut. Ziegler reported to a colleague: “During the entire first week we had extraordinary good business, and thus far we have to report only one disappointment and that is the new dramatic soprano, Konetzni, who did not turn out to be up to standard. Konetzni is only engaged for five weeks, so that we are not going to be punished much....Lotte Lehmann came in on New Year’s Day and sang a gorgeous Elisabeth, in fact the whole Tannhäuser performance was about the best I ever heard. Melchior and Tibbett were at the very top. Last night we gave Forza del Destino with Rethberg and never since I have known her has she sung as she did last night. She is in marvelous voice, and is making the best use of it, which makes me correspondingly happy because, confidentially, Rosa Ponselle won’t sing this role anymore because she says it is too high for her, or too something....So far as our future is concerned, there are no plans as yet. We are still doing a lot of budget making, thinking and discussing, but the crux of the whole situation is the lack of funds. How it will end I don’t know.”

FLAGSTAD IN NEW YORK

(Astor Hotel)

(Astor Hotel)

Little did he—or anyone else, for that matter—know their salvation had arrived in town on January 8. Once Flagstad and her husband had settled into their suite at the Astor Hotel and gotten a bit acclimated to their new surroundings Flagstad wrote to her mother about their first few days:

“Mother dearest,

“I suspect you have been waiting to hear from me, but I wanted to wait until I had something definite to report. The journey was nice, very little heavy sea, so I, we, were up and about all the time and enjoyed the relaxation and not least the food and nice company on board. We arrived in New York Monday 7th but due to heavy fog were unable to get ashore until Tuesday evening. I can tell you that sailing into New York in the evening was spectacular. The Statue of Liberty emerging from the fog and all the lights on the skyscrapers—it was amazing. We live at an excellent hotel and we have two rooms and a bath. We got the grand piano from the theater yesterday so it is quite cozy here. 9th floor with a view on two sides, especially at night with all the neon signs: it is a fantastic view. The thing is that we live in the center of the city, close to Broadway. It takes me 5 minutes to walk to the Opera which is quite practical. We are often invited out, but I have to ask most people to wait until later, as I have so much to do and am dead tired early in the evening, probably because of the many new impressions, the language and the work. My English surprises me, I manage nicely and besides English, I also have constantly to speak German, so my brain is somewhat overworked. I am overwhelmed with all kinds of requests for advertising and publicity, but answer none, it is massage, photos, clippings and other things like that. The weather was very hot the first days, but now we have clear sky and sunshine, it’s cold and partly snow that won’t stay for long and yesterday it was a violent hurricane, ice cold. The climate is said to be quite dangerous for singers, but so far I am perfectly all right, as to voice and body.

“Friday we were at the Opera for the first time and listened to Siegfried with Melchior and Mme. Konetzni, new here and has had no success; she is famous in Germany. The scenery was in a state of decay and when you have been to Bayreuth...

“From the orchestra I heard a lot of nuances, there were more than 100 musicians and the sound was magnificent. We were dressed up in grand gala and you must believe the audience was impressive! Yesterday we listened to Der Rosenkavalier, it was quite lovely and I merely state the fact that it is beyond any human being to sing the Marschallin without any orchestral rehearsal or a lot of other rehearsals.”

The day after they arrived, Flagstad and Johansen reported to the Met and talked with Gatti, Ziegler, and Bodanzky who noted approvingly that she was as slender and youthful as she had been at her audition. Flagstad asked to be relieved of the Marschallin and, considering everything else she had to learn, this was agreed to, which was a great load off of her mind. She was asked to come back the next day and let them hear her again before they decided which parts she would actually do. As Flagstad explained it, “We had Götterdämmerung, and I was beside myself with fright. Except for practicing all parts every day on board ship I hadn’t sung a tone for several days; texts, everything was swept from my mind. Bodanzky said it would be better to wait and give me respite with my part until Sunday [January 13].” On that occasion Flagstad sang her part flawlessly and Bodanzky “was extremely friendly and encouraging.”

All the operas Flagstad had been hired to sing were already in performance with the exception of Götterdämmerung. Though Gertrude Kappel was already scheduled to sing Brünnhilde in the first performance, it was decided to have Flagstad sing the dress rehearsal of the Prologue and Act One on January 15 for the simple reason that no one at the Met had ever heard her in actual performance! They had no idea how she would sound with an orchestra, how she would look on stage in costume and makeup.

It is a rehearsal that has become legendary. After a false start (she was singing into the wings), Flagstad set the place on fire. Unlike many singers, Flagstad always sang rehearsals in full voice, and when she opened up that morning people were amazed. One story is that tenor Paul Althouse, her Siegfried, was so astonished he missed his cue. What is verified is that Bodanzky was simply flabbergasted at what the Met had found in their newest soprano. He turned the rehearsal over to an assistant and ran to get Edward Ziegler. Helen Noble was Ziegler’s secretary and she described what happened: “BANG! went the door one January afternoon in 1935 and there stood the usually calm, dry Bodanzky in the open doorway [to Ziegler’s office] electrified with excitement. His eyes were popping and his arms cutting the air as though he were still conducting. ‘My God, Ned! My God! Come hear this woman sing!’ He turned and dashed back toward the auditorium, Mr. Ziegler hot on his trail. I couldn’t resist. I followed too.

(KF as Brünnhilde)

(KF as Brünnhilde)

“A woman was standing on the stage. Great round golden luscious tones poured out with ease, filling the huge space of the auditorium with magnificent sound. A voice made for Wagner’s music…She stood relaxed, unemotional, her hands clasped loosely. None of the usual tenseness, wetting of lips, tightened throat muscles, or other symptoms of nervousness so often found in first rehearsals. Such simplicity and poise—so very effective. I could not take my eyes from her. I was dying to know the effect upon my Boss, so I tiptoed down the aisle and took a quick look at him. Just as I expected, he was so absorbed that I doubted if a clanging fire engine would have disturbed him. Wagner was Mr. Ziegler’s dish and it was being served to him at its best.”

The auditorium began filling rapidly as word raced through the entire building: Drop everything and come hear this voice! When Flagstad hit her sumptuous high C at the end of the Prologue duet, her voice sailing effortlessly over the huge orchestra, Bodanzky shouted “Flagstad, superb!” The orchestra stopped playing and cheered. People in the auditorium applauded loudly. The stagehands cheered. “We had to sing the duet three times that day,” Flagstad wrote her mother. “Bodanzky came up and was very enthusiastic, and so was Mr. Ziegler. Well, all were more than enthusiastic, and the stage director said I was so capable and lovely that I did not need to do anything special—my appearance on the stage and my bearing were enough. Such a demonstration by the orchestra was unheard of here, they said.”

After the rehearsal there was another huddle with Gatti and Bodanzky. It was decided Flagstad would make her debut as Sieglinde during the February 2 Saturday matinee, since there would be no opportunity for her to have a rehearsal and Sieglinde was a role she already had sung on stage in German. Also the Saturday matinee audience was the smallest of the week so it would be a way of cautiously easing her into flow of the season. After that she would sing Isolde on the 6th, the Walküre Brünnhilde on the 15th, and Siegfried on the 22nd. “Bodanzky warned me against the agents who would come in droves, and he asked me to consult with him on everything,” she wrote her mother. “He pinches and pats my cheek and treats me like a little girl. Yes, everyone here seems to think I am ten years younger than I am, and that is wonderful.”

The Met management decided that, despite everything they had just heard, they would not make a big deal of Flagstad’s upcoming debut, do no big build-up in the press, but let the public discover her for themselves. Or was the Met, perhaps, being a bit overly cautious, lest the Götterdämmerung rehearsal be something of a fluke, something that would not happen to that extent in actual performance?

Meanwhile people were asking, “Who IS this woman? Where has she been? Why didn’t we know about her before this?” And, from those in the know, “Why was she only hired as a replacement artist?”

Eric Simon pointed out that the room where her audition had been held was the least conducive possible for truly evaluating a voice with all the heavy upholstery and drapery. While that’s true, it is also true that Flagstad’s voice had been slowly growing over the years. She had never pushed it to do more than it naturally could and singing—singing correctly—so much Wagner over the last couple years had developed her voice to its peak. In addition, a large voice makes its maximum impact in a large space where it can blossom freely. The Met’s auditorium was twice the size of the largest theater in which she had sung before. It was the perfect setting for Flagstad’s voice, at its peak, to sing the music which showed off her artistry at its finest.

Though Flagstad continued working hard on her upcoming roles, she and her husband took full advantage of being in New York. In addition to numerous performances at the Met they took in lighter fare, like Ginger Rogers in Romance in Manhattan, Margaret Sullavan in The Good Fairy, both at Radio City Music Hall, and Gary Cooper’s Lives of a Bengal Lancer at the Paramount. Flagstad’s diary for the last two weeks in January reads like the schedule of an hyper-active tourist, not that of an anxious debutante.

One evening during an intermission at the Met, Flagstad and her husband were standing on the sidelines when an elegantly dressed woman came up to them. “Are you not the young singer who sang the Götterdämmerung rehearsal the other day?” she asked. When Flagstad shyly answered yes, the woman introduced herself—Becky Hamilton—and said her husband was one of the shareholders of the opera, and when she had heard Flagstad’s Gutrune at Bayreuth that summer she had been so impressed she had put a cross next to Flagstad’s name in the program. She had also been at the Götterdämmerung rehearsal and was very much looking forward to Flagstad’s debut. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the two women.

The Met had released so little about Flagstad to the press that critic Pitts Sanborn groused in one of his columns, “Kirsten Flagstad, a Norwegian soprano, soon to be heard at the Metropolitan, is reported to have sung at Bayreuth. Will some benevolent statistician kindly tell when and what?” The day of her debut, her photo appeared in The New York Times. Another paper, The World-Telegram, had large photos of other singers, Eide Norena and Mary Moore, an American soprano scheduled for her debut as Gilda in Rigoletto the following Friday. But the New York music world is a very small place and everyone who had been at the Götterdämmerung rehearsal had told the story to others. As a result of the underground buzz every important critic in the city was at the opera house the afternoon of February 2.

THE DEBUT

About 10 o’clock the morning of her debut Flagstad said to her husband, “I think I will take a little walk in the city." Around twelve she came back to the hotel. "But aren't you going to drive to the opera now?" he asked. “There's no hurry,” she said. “It’s all right if I am there at 12.30. I don’t need more than half an hour to get ready." Johansen’s daughter Kate had impulsively decided to come to New York for the occasion, waiting until she was in the middle of the Atlantic before cabling that she was on her way. She recalled, “Kirsten wandered around the hotel rooms as calmly as if she had been at home in Tidemand Street. Father and I were the ones who were nervous: we were so accustomed to Kirsten taking care of herself and not fussing over anything that it didn't occur to us to escort her to the Metropolitan when she left to get ready for the performance.”

The cast that afternoon included Paul Althouse as Siegmund, which must have been something of a comfort for Flagstad since he had been her Siegfried in the Götterdämmerung rehearsal, Emanuel List as Hunding, Gertrud Kappel as Brünnhilde, and Maria Olszewska as Fricka with Bodanzky conducting. It was only the third time Flagstad had sung Sieglinde and she had no rehearsal.

(Paul Althouse) (Gertrude Kappel)

“As we sat in the auditorium and observed the sophisticated audience, seemingly occupied only with chattering with acquaintances, I wondered with dread how Kirsten would get on,” Kate said.

It was the most astonishing debut in the history of the Metropolitan Opera, a house that is studded with a rich history of sensational debuts. As impressive as were the debuts of Ljuba Welitsch, Leontyne Price, Franco Corelli, Birgit Nilsson, Joan Sutherland, etc., their reputations preceded them. They all had won acclaim in Europe, or in other theaters in the U.S., so audiences had a good idea of the treat that was in store for them when the artists finally reached the Met. But when Kirsten Flagstad made her Met debut she was virtually unknown on this side of the Atlantic. Before coming to the Met the two roles she had performed more often than any others were Micaëla in Carmen (47 times) and Marguérite in Faust (41 times). The roles for which she is best known today she either sang for the first time in the U.S. or she had sung only a handful of times before her Met debut totally changed the focus of her career. The most astonishing singer seemed to have appeared magically, out of thin air, ready to tackle with impunity roles that other sopranos found daunting, to say the least.

As W. J. Henderson, the dean of the New York critics put it the next day, “It was a performance that began in calm and ended in pandemonium.” During the first intermission, Geraldine Farrar, who knew first hand about the art of singing and what it takes to totally conquer an audience, threw away her script to tell the Met’s radio audience, “Ladies and gentlemen, today we are witnessing one of the greatest events that can happen during an opera performance. A singer completely unknown to us has transported the audience to ecstasy with her marvelous voice and artistic personality. A new star is born!” (Click here to listen to Farrar during the intermission)

It was also during the first intermission that Gatti-Casazza got a telephone call in his office. It was the feisty New Zealand soprano Frances Alda who happened to also be Gatti’s first wife. She was calling from her home in Great Neck, Long Island, where she had tuned into the broadcast late and missed the announcement of the cast.

“Who is that singing Sieglinde?” she asked.

“Perchè?” asked the laconic Gatti. (Why?)

“Perchè a una bellissima voce a canta molto bene.” (Because she has a beautiful voice and sings very well.)

“Una certa Flagstad.” (It’s a certain Flagstad.)

During the first intermission, as her colleagues were congratulating her, Paul Althouse mentioned to her the performance was being broadcast and asked if she had any idea how many people were probably listening. “Perhaps a hundred thousand,” she replied, thinking she was exaggerating. Althouse laughed. “You can figure on ten million,” he said. Flagstad was stunned—more than three times the population of Norway!

Despite the fact that Sieglinde has little to sing in Acts Two and Three, the audience that afternoon remained riveted on Flagstad. And when she left the stage in the middle of Act Three, clutching the pieces of Siegmund’s sword, something unique in the history of the Met occurred. The audience erupted in applause.

After the performance the audience stormed the stage and the ovations seemed endless. “What completely took my breath away was the tribute of the audience to me personally. I was not unfamiliar with applause, but the way the Americans showed their enthusiasm completely overwhelmed me. I felt ecstatic when it was all over, and I realized that my debut had been a success. But I was so dead tired that I only wanted to rest. My husband, Kate, and I walked back to the hotel, as fortunately no arrangements had been made to celebrate my debut.” In an interview back in Norway she said, “After my debut the orchestra sent me a cable and wished me many years at the Met. Have you ever heard anything so strange?”

The reviews the next day were all any soprano, or any opera company, could wish. And they all mentioned that on Wednesday she would be singing Isolde, a role infinitely more complex than Sieglinde. Her first Met Isolde was only the sixth time she had ever sung the role and again she had to do so without a rehearsal. It was also the first time she sang with Lauritz Melchior. The performance confirmed what her debut had promised—here was a voice that comes around once in a century, a beautiful, limpid voice of astonishing breath control and great musicality that seemed to simply float effortlessly on top of the largest orchestral waves without ever losing color or texture. All the critics agreed that on stage she seemed to be the essence of femininity, the perfect physical embodiment of the characters she played.

Lawrence Gilman seemed to sum up the spell Flagstad cast on New York in his Herald Tribune review of that first Isolde: “Last night’s performance of Tristan at the Metropolitan was made unforgettable for its hearers by a transcendentally beautiful and moving impersonation of Isolde—an embodiment so sensitively musical, so fine-grained in its imaginative and intellectual texture, so lofty in its pathos and simplicity, of so memorable a loveliness, that experienced opera-goers sought among their memories of legendary days to find its like. They did not find it….

“And always, throughout, Mme. Flagstad is the finely musical artist who knows the significance of the words she sings, and the shape and rhythm of the musical phrases that enclose them, and the quality of the tone they need for their conveyance.

“Always the voice itself is pure and noble and expressive, of a beauty that is often ravishing to the ear, and a power and clarity that are equal to every demand that is made upon it by the music.

“This is not a review of a performance of Tristan und Isolde: it is a hurried note upon a new Isolde, one of the rarest, perhaps the rarest, of our time: an embodiment so deeply sensitive in its imaginative truth, of so exalted and enamoring a beauty, that the function of the critic becomes, in its essence, a mere opportunity to exercise his highest privilege—what Swinburne called ‘the noble pleasure of praising.’”

Fortunately for opera lovers today, both of her radio broadcasts from that first season survive on CD. Of the debut in Walküre we have Act One complete and all of Sieglinde’s part in Act Two. Alas, nothing seems to have survived from Act Three. Her second Tristan on March 9 is complete. It was only the seventh time she had sung the role she would eventually do almost 200 times, and gives a very good idea of what all the fuss was about.

Click here to listen to Flagstad's debut in Walküre

Click here to listen to the Tristan duet with Melchior

By the end of her first season at the Met—a period of three months—Flagstad was one of the most famous figures in America. And this in the days before social media—no Tweeting, no Facebook, no YouTube or Instagram. She and Melchior made Wagner the hottest ticket on Broadway. Cole Porter put her in the title song of his 1936 musical Red, Hot, and Blue, the ultimate accolade at the time for someone to have “arrived”: “I’ve no desire to hear / Flagstad’s Brünnhilde, dear, / She waves a pretty spear, / But she’s not red, hot, and blue.” By the end of that first season she had brought in $100,000 for the Met, which guaranteed the Met would have a 1935-36 season. It was her presence at the Met that saved the company from going under during the Great Depression.

When Gatti-Casazza was interviewed by reporters, just before he left the U.S. and retired to Italy, he said, “I have given America two great gifts—Caruso and Flagstad.” Clearly she was no longer “a certain Flagstad.”

Paul Thomason, July 2020

Click here for the author's website with many more articles of interest

Sources:

The Flagstad Manuscript, an autobiography narrated to Louis Biancoli.

Flagstad, A Personal Memoir, by Edwin McArthur

Life with the Met, by Helen Noble

Flagstad, Singer of the Century, by Howard Vogt

Numerous articles, files, and observations shared with me by the late Robert Tuggle, head of Archives at the Metropolitan Opera, who was working on a biography of Flagstad at the time he died.