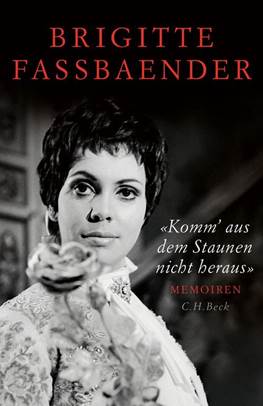

BRIGITTE FASSBAENDER : Memoiren “Komm’ aus dem Staunen nicht herab"

C.H. Beck Verlag München (381 pages – Hardcover 26.95 €) + Click here to order the book !!!

*Click here for Fassbaender herself interviewing Gundula Janowitz

**Click here for a TV interview (German only) and here for a more than 100 minutes wonderful portrait

The title is an outcry by Ochs von Lerchenau from Der Rosenkavalier by Hugo von Hoffmansthal; music by Richard Strauss. Somewhat freely translated it means “I can’t believe my eyes”. Of course the one role one associates Fassbaender with will always be Octavian in the same opera. This book starts for almost 200 pages as a chronology of her life while afterwards she gives a detailed diary on her experiences as a producer and her production of Midsummer Night’s Dream in Amsterdam while in the third part of the book she discusses her productions of several war-horses in her later career. Most readers will be interested in her singer’s career though her reminiscences as a producer are worthwhile too. In her introduction she informs us that she refused the help of a ghost writer and thus is responsible for every printed word.

The book starts out with a very frank discussion of her family ‘s private lives. No quarrel, no adulterous relationship as far as she knows is deleted. And then all at once there is the almost prudish reversal when discussing her own life. There is a short sentence that after several years of marriage she discovered she didn’t only love men but women as well (as everybody with a knowledge of opera and opera singers has known for decades). So what’s the big deal? Why that secrecy when the whole operatic world knows she has been living for more than half her life with her English friend and manager Jennifer Selby to whom the book is dedicated? (initials only in the dedication and it seems her companion’s full name is only mentioned once. I have not been able to spot it). In another surprising reversal she tells of the difficulties a singer -especially a singer specializing in trouser roles- is confronted with. She admits that during her career there was not a diet she didn’t try out to retain her small and svelte figure. This cannot have been easy as she frankly writes she was too fond of several drinks after performances. Indeed, she admits there were quite a few nights when she simply couldn’t remember how she got home.

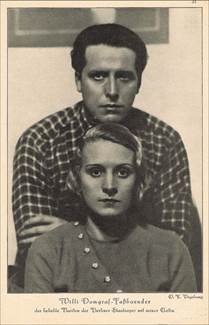

In her first chapters she tells us of her horrid experiences as a small child in the German capital during the horror years of 1944 till 1946. Discreetly she pities the destiny of her mother when the Russian soldiers “liberate” and rape Berlin. If one doesn’t want to be banished nowadays in politically correct German circles she has to make the right moves; that means damning her parents of sympathizing with the Nazis. Nevertheless she cannot and will not deny she started out her career with miles of advantages on other singers. She is the daughter of baritone Willy Fassbaender (who added Domgraf to his name to avoid confusion with another singer).

(Fassbaender's father with his then wife) + click here to watch him sing Largo al factotum (1938) + click here for a film song (1932)

(Fassbaender's father with his then wife) + click here to watch him sing Largo al factotum (1938) + click here for a film song (1932)

Father Fassbaender was one of the pillars of the Berlin operatic scene, a movie star and a charmer. He had a high lyric baritone who concentrated on Italian roles after one bad experience with Hans Sachs and his records prove that a German can sing Italian arias and duets (even in German) as well as someone born south of the Alps. Without doubt nowadays he would have had a world career. After the war he became head of productions in Nuremberg. Therefore from her earliest youth Fassbaender lived in a world where opera’s, lieder and classical instrumental music were abundant. She wants us to believe that as a young girl she was soon aware of her vocal talent and hid it from everybody. But one day she relented and from Berlin sent an example of her voice to her father in Nuremberg. He immediately reacted with an invitation to teach her. All’s well that ends well but I’d have it appreciated if Fassbaender would have taken more pains to discuss her voice in depth. Once more she is very reserved; doesn’t mention the extension of the voice, the volume, the strong and the weaker points and limits herself to “androgyne”. Chapters later we get the important information she recorded Azucena with Giulini and she says she would never have been able to sing the role in the theatre. Her voice indeed was a fine textured warm mezzo with enough volume to fill La Scala or the Met without problems. It didn’t have the cutting edge of a real Italian mezzo and she specialized in Mozart, Strauss and Wagner (Brangäne, Fricka and Waltraute; no “Entweihte Götter” for her). Still she doesn’t explain how someone not being able to sing Azucena took on several performances as Eboli and Amneris. As Berganza she was a credible Carmen and an inspired Charlotte and she puts singing and acting on the same level. Many people will remember Fassbaender for her outstanding Lieder recitals. She broke gender prejudices by singing Schubert’s Winterreise and Die schöne Müllerin.

Fassbaender started her career at 22 with small parts; being almost every evening on the scene in München. But everyone soon recognized her talent and two years later her comprimaria days were already over. From there on it was only way up though she never became a real world star with a household name famous outside operatic circles. But everybody (managers, conductors, directors and especially audience members) knew that her performances and concerts were more than reliable. Here was a serious artist that gave unmitigated pleasure, seldom had off-nights and liked to sing difficult repertoire. In her stories of the theatre she is often generous for her colleagues; made easier by the fact that a mezzo seldom is the prima donna of a performance and doesn’t have to stab soprano competitors in the back. She speaks with warmth of other singers like Wunderlich and Janowitz and has a few axes to grind with Karajan and Domingo. The conductor didn’t take a no for a role for an answer and banished her from his circle. The tenor with the groping hands and wet kisses tried to seduce her, was pushed away during rehearsals but profited during scenic performances of Werther to behave in the way that broke his career and reputation (this page was written before the me-too accusations were made).

After a career of 28 years she combined the life of a singer with the job as a producer for six years as well. This was the solution to the rising problem of her menopause which she is not shy to discuss and caused her a lot of worries. Fassbaender tried hormone therapy, reworked her singing technique without success, got more and more nervous, still gave some performances of Clytaemnestra at the Met at the end of 1994 and started the new year with a blunt letter to everybody concerned that her singing days were over. She started as a head producer in Brunswick and two years later became general manager of the Innsbruck opera house in Austria; courtesy of the local female mayor who wanted a female boss. Fassbaender devotes some interesting pages on the problems of running a small house; on financial difficulties, on triumphs she got and big mistakes she made by bad choices of repertory, on the way she was side-lined when her contract was not renewed.

The second part of the book is no less interesting. It is almost a day by day diary of her experiences as a producer at the “Nederlandse Opera” in Amsterdam from September 1991 till October 1993. At the time she still combined singing and producing. Even with this handicap it remains a stunning story of incompetence by many people, downright laziness, artistic pretentiousness and throwing taxpayers’ money in the drain e.g. general manager Audi flying to meet Fassbaender in Britain for a small chat and a nice expensive dinner afterwards. It probably is not Fassbaender’s aim but her stories confirm this reviewer's opinion that a lot of operatic concepts and so-called artistic choices are just baked air. Many a theatre could do well with less money if everyone concentrated on working instead of talking. All in all an interesting book with two deficiencies. There is no performance chronology and the section on recordings is just a list without detailing Fassbaender's role (often very small in some operetta recordings) or mentioning other singers; limiting itself to “Lieder von Schumann”. Nevertheless I was surprised to notice that the mezzo recorded 29 lieder recitals and only one operatic one. The book has an index.

Jan Neckers, April 2020