Elizabeth Nash: GERALDINE FARRAR, Opera’s Charismatic Innovator,

Review by CHARLES MINTZER

McFarland Press, click here to order the book

185 pages USA$45.00; phone orders: (USA) 800-253-2187

(all photos courtesy Charles Mintzer collection)

On the cover of this rather expensive, slim, soft cover book, it says “Second Edition.” I was puzzled because I did not know of the “first” edition, and I thought I was generally knowledgeable about opera singer biographies. According to the preface, this new edition supplements the successful “first” edition. Again I had to scratch my head, “Where was I” that I missed in 1981 a serious book/study of Geraldine Farrar? It turns out that the original book and this “second edition” was the college dissertation of Elizabeth Nash, who it says in the preface, had a ten year career as a singer (google: coloratura soprano 1961-70 Kassel, Osnabruck, and Detmold), then joined the faculty of theater arts at the University of Minnesota. The extra feature of this slender volume is the incorporation of some of the memories of Camilla Williams (1919-2012) who had been befriended by Farrar early on her career. Farrar actively supported and encouraged the budding career of one of the first African-American singers to break the color barrier shortly after World War II. We are now privy to Farrar’s advice, and by focusing on a few selected roles, alerting the young Williams to the needs and pitfalls of these roles and of an operatic career.

Ms Nash floats the interesting theory in her thesis that Farrar was one of the very first singers to integrate genuine acting into her various roles, thus joining the elite company of Emma Calvé, Feodor Chaliapin and Mary Garden, the then rare artists who created believable stage figures. The subtitle of the book is “Opera’s Charismatic Innovator.” She maintains that singers like Adelina Patti and Nellie Melba were merely canaries whose artistic credo was to offer the public highly-cultivated vocal art with its full armory of amazing technical skills. Neither Patti or Melba, who often sang Marguerite in “Faust” (a major role of Farrar’s) ever engaged in physical acting in that opera, just an occasional pose. I think it is an exaggeration to claim that before Farrar, even before the other singers mentioned, there were no brilliant singing-actors in the nineteenth century; that assertion flies in the face of many documented accounts of some amazing stage realizations; (think Luigi Lablache, Victor Maurel and Jean de Reszke), but I would accept that for the most part the acting component of opera was largely secondary. I think Ms. Nash is on more solid ground when she disdainfully describes the almost non-existence of meaningful stage directors. The stars usually brought their own costumes, often Paris creations, and the flat scenic backdrops of the time often flapped. She states that when Puccini came to New York to supervise the 11 February, 1907 Met premiere of “Madama Butterfly,” they had only two full stage rehearsals before the final dress rehearsal. It is interesting that Farrar did not sing rehearsals in full voice, and Puccini wondered to confidants if she would be heard in the large theater in a regular performance.

(first photo AMICA, world premiere Monte Carlo 1905, second as Elsa in Lohengrin)

(first photo AMICA, world premiere Monte Carlo 1905, second as Elsa in Lohengrin)

As the bulk of the book is a narrative of her roles at the Met with generous quotes from the New York and out-of-town critics, one misses the other part of a famous singer’s story; the interpersonal relationships and the feuds. Ms. Nash however possesses the wonderful skill of stitching together Farrar’s career narrative with pertinent reviews, mostly good ones, but occasionally, just for balance, some negative comments. The selected reviews are a welcome choice for they often reveal the multi-faceted aspects of Farrar’s continuously developing artistry.

We know from other accounts of that era that Farrar really disliked dramatic soprano Emmy Destinn (1878-1930) dating back to their rivalry in Berlin (1901-1906) , and later Maria Jeritza (1887-1982), but one would never know that from this book. Her love life with its many men (and some speculate, women) is not explored. In most studies I have read of Farrar there is more than speculation about her long affair with Toscanini when he was the lead conductor at the Met and the German Crown Prince when as a young singer she was a star at the Berlin Royal Opera. I think the included quote, when Farrar was asked by a reporter in 1936 for a reaction to the grizzly suicide death of her former husband of seven years, the Dutch actor Lou Tellegen who was suffering from cancer, “I have nothing to say and am not interested” speaks volumes of her ability to “move on.”

One of the very useful inclusions in this book is the detailed listing of Farrar’s fourteen Hollywood movies made between 1915 and 1920. I think it is fair to say that Farrar was the most successful of the many opera stars that ventured onto the silver screen. And yet Farrar never allowed her cinema success lure her away from her first callings: opera and concert; only going to Hollywood to make movies in the summer off-season of the Met. This speaks volumes of her high seriousness, which from Ms. Nash’s quoted opera reviews inform the reader of the diligence she invested in her stage characters. For Cio-Cio-San she bought Japanese art and engaged a Japanese maid, in order to study the authentic delicate and subtle movements. She asked the original Tosca creator (on the stage) Sarah Bernhardt to help her understand and develop the character on the deepest level. Whether one reads the review quotes in this book or those on the Met’s database (www.metopera.org archives, database, key word, Farrar review) one knows that her stage creations were always growing, they were “works in progress.” She was constantly adding and subtracting details to her impersonations. And the critics felt in reviewing a later Farrar performance after the premiere, that there would be some new character development to note.

For those interested in Farrar the woman, there is very little in the book after she leaves the opera (1922) and concert (1935) stages. In the early days of the Met broadcasts, Farrar was often the host, explaining the story and accompanying herself on the piano in excerpts from the broadcast opera to make her musical points :

At the Flagstad debut in 1935 she allowed herself to comment on the historic nature of the event. Farrar also maintained a voluminous correspondence and was outspoken with her strong artistic, social and political opinions. (see below).

There is no doubt that Farrar was a huge star, one of the all-time greatest. She possessed an attractive lyric soprano capable of dramatic accents that was trained by several estimable teachers, including the formidable Lilli Lehmann. (a fine and representative compilation of her work is on the Marston label: http://www.marstonrecords.com/farrar/farrar_tracks.htm ). She often consulted with leading stage figures including Sarah Bernhardt re stage presentation. As a highly attractive woman she was a natural celebrity and good press fodder, for in addition to her physical beauty she was highly articulate and could defend herself and her opinions to a press that was eager to publish anything she said. As an American artist of excellence she commanded huge attention and admiration in her own country. The book states she sang 493 times at the Met (in New York); the total Met figure is 672 (New York and the national tour). Statistically it is one of the most impressive and important careers in Met history. Her 139 Cio-Cio-Sans alone rivals Antonio Scotti’s 217 Scarpias as the largest role total of a leading singer. Some others of note are: Calvé’s 137 Carmens, Caruso’s 116 Canios, Martinelli’s 124 Radameses and MacNeil’s 102 Rigolettos. Farrar also amassed other significant totals with her 67 Toscas, 65 Carmens, 59 Margueritas and 39 Goose Girls in Königskinder.

In summary, Mr. Nash’s book is a valuable distillation of Farrar’s American operatic career, read Metropolitan Opera. She not only makes but stresses her basic point that Farrar was a singing actress as much as a pure singer. She indulges in the cliché that she was a singer who would rather make an ugly sound if it strengthened her dramatic point. Her Hollywood period emphasizes that she could really act; after all, these were silent films in which she starred. For Farrar the large-scale personality one has to search other sources.

GERALDINE FARRAR LETTERS

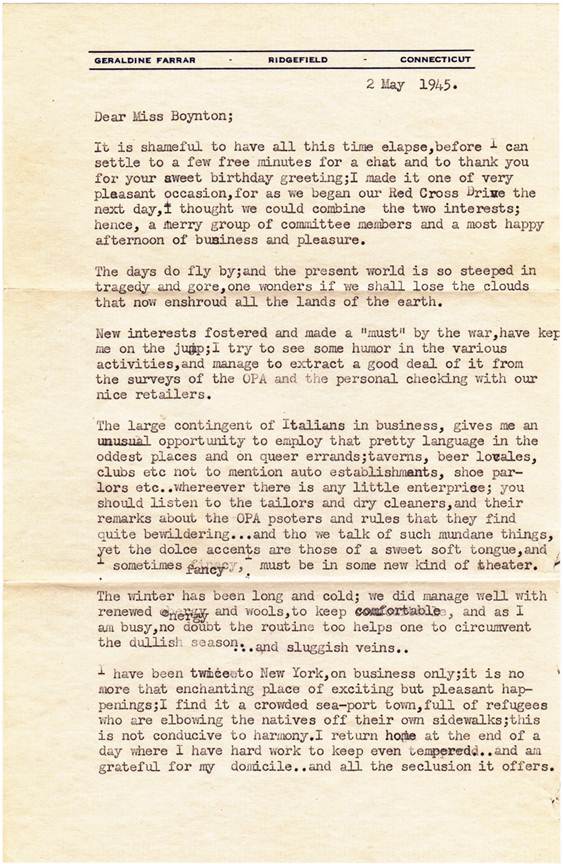

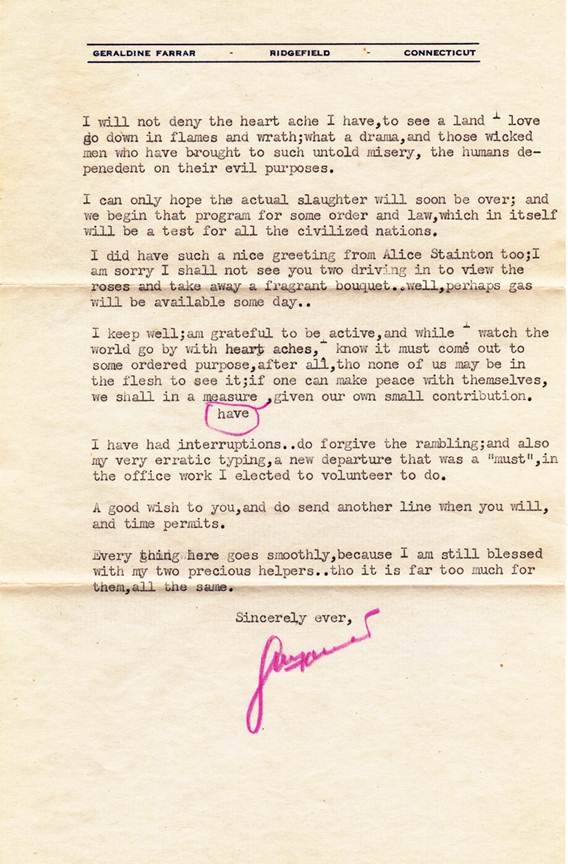

(as a volunteer during WWII)

(as a volunteer during WWII)

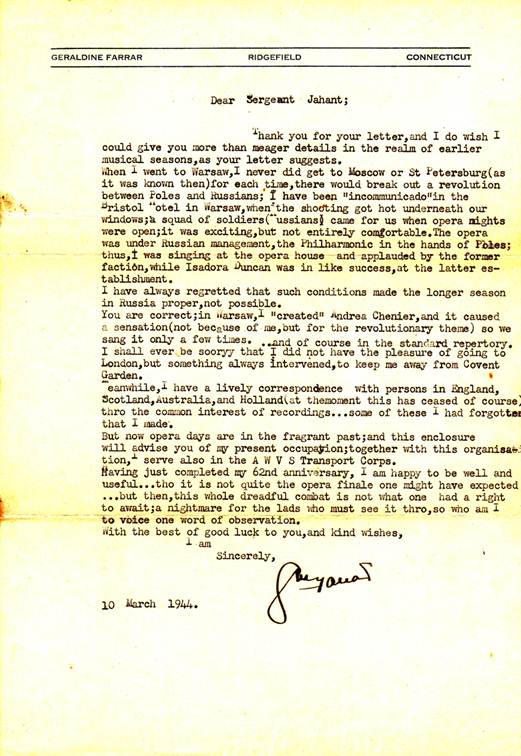

I was lucky to inherit almost a hundred Farrar letters from a retired “Gerryflapper,” Claudia Boynton of Chicago and later Leesville, South Carolina, a woman who as a young girl became fascinated with the Farrar phenomenon and carried on dedicated correspondence with her from the early 1920s until Farrar’s death in 1967. Many of the notes and cards in the collection I inherited are merely “thank-you”s for birthday and Christmas greetings, but during the 1940s when Farrar was doing war-related volunteer work she let her hair down in long typewritten letters and the multi-faceted woman emerges. Her strong American patriotism comes through as well as her rock-ribbed New England conservatism.

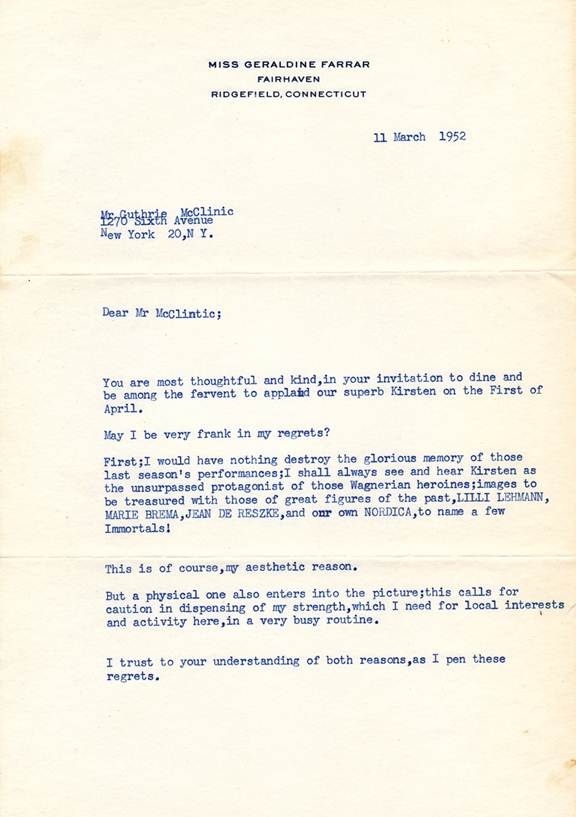

(letter to Charles Jahant, click here to read more about him)

(letter to Charles Jahant, click here to read more about him)

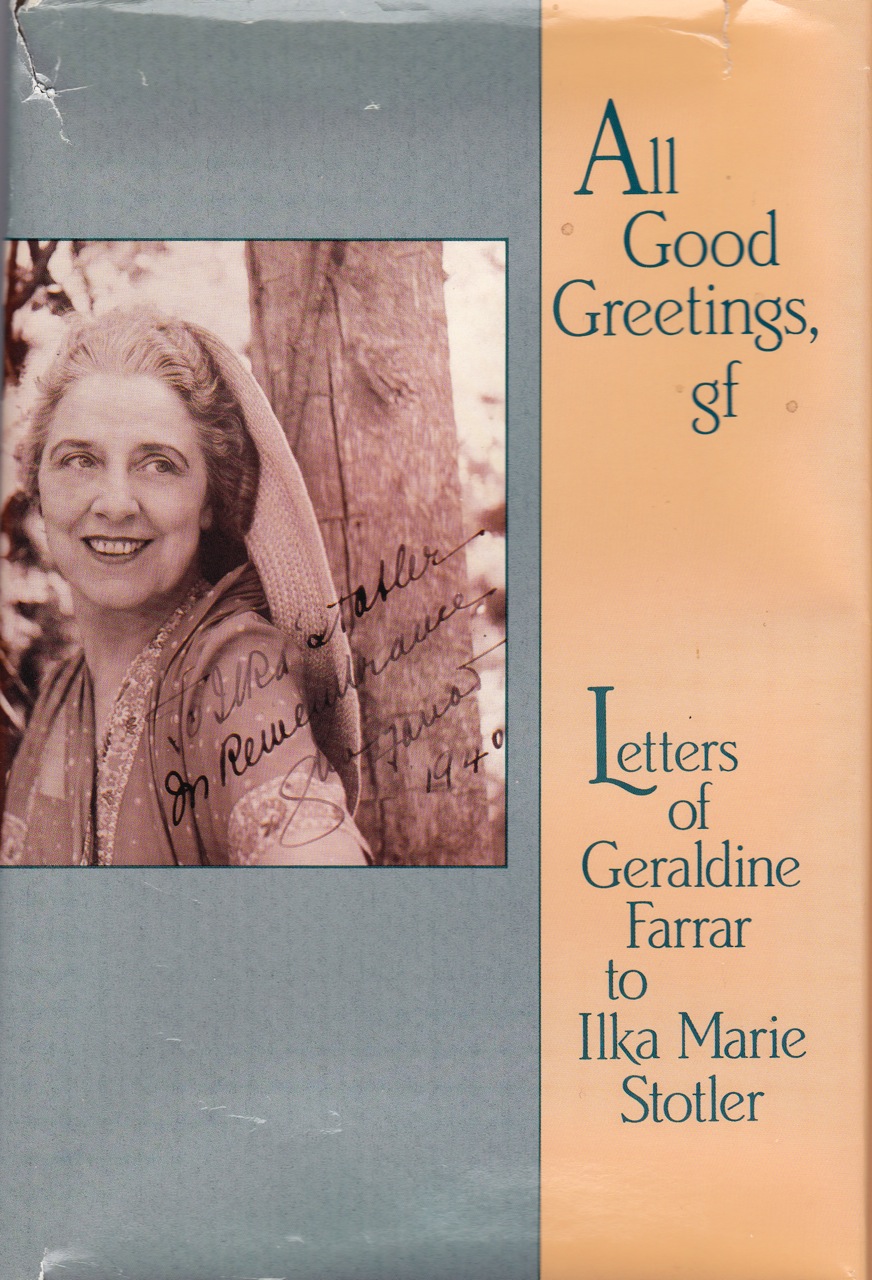

Farrar’s letters to Marie Stotler, a fan who became a friend, were published by Stotler’s niece in1991: ALL GOOD GREETINGS: LETTERS OF GERALDINE FARRAR TO ILKE MARIE STOTLER, 1946-1958. 1991 University of Pittsburgh Press. Interspersed in Farrar’s letters to Miss Stotler are snatches of opinion about singers and performances she heard in New York or on the radio or television, and on occasion recordings. Going through the book I am quoting items that I think would be of some interest to readers of this website. These musical and operatic comments are not the total focus of these letters for Farrar is very vocal about national and international politics, food, gardening, health, and everyday concerns. If one wants to understand the deeper underpinnings of Yankee conservatism and Republicanism, Farrar’s frank opinions are a good start.

1947

In a letter postmarked 20 November 1947: “Yes, the radio “Tosca” was very bad. I listened carefully to all three acts; there was not merit in it.” The 1947 “Tosca” broadcast from the Met (Elen Dosia, Jan Peerce, Frank Valentino)

In a letter postmarked 22 November 1947 she allows herself to speak of fabled Italian actress Eleonora Duse and compare her to Sarah Bernhardt: “I was not an ardent admirer of this strange lady, though I am willing to credit a zealous press agent in the matter of her soulful misery and constant suffering. I think she was a neurotic, a hardworking artist, and certainly not in robust health, but to play roles of glamour and youthful passion, it gave me no pleasure to see a woman of years without make-up, artifices or illusion, gray hair in untidy profusion and awful dresses…She did nothing to help herself at the age when I last saw her, whereas Sarah Bernhardt was an element of any illusion she chose and what a voice! Duse’s was a wail most of the time. To my way of thinking, the theater “is” the theater, and should create illusion especially in the realm of poetry and legend.”

9 December 1947 she talks about the broadcast of Otello with Toscanini and the NBC Symphony: “Talking with the Maestro’s [Toscanini’s] secretary this morning, preparing for the second half of Otello [on radio] he tells me the rehearsals were twice daily with cast and orchestra. No wonder the results are perfection. Yet one of the smaller singers ventured to remonstrate, saying that she could not come back for the last rehearsal, but that she would, even so, be letter perfect. This is indicative of the young people today – no idea of any concentration or joy in work. Imagine the “glory” any of us older singers would have felt to be chosen for such an occasion The hours we rehearsed, without food or rest, all intent on the lovely results, and these little nit-wits – truly it is to despair that ever again we shall have first rate performances.” [Could Farrar be referring to Nan Merriman, the Emilia, the only other female in the cast other than Herva Nelli, the Desdemona?]

On 11 December: “The Otello with Toscanini was rarely beautiful. It just goes to show what careful preparation and a certain amount of talent will do. Singers blossomed out under the Maestro’s baton. He told me he had rehearsed them two hours morning and afternoon, for four weeks. Well, the results indeed repaid his care.”

In the same letter she mentions Mary Garden [1874-1967], the one singer to whom she was most often compared, and many people believed they did not admire each other. “Miss Garden has, as yet, brought forth no book but she should. It would be good reading of a fascinating era. She comes from Aberdeen, but has lived here from her early youth. Her father was in the automobile business, Packard, I seem to recall, while her mother and a second daughter were present. Miss Garden was a protégé of a wealthy lady (as we have all had the good fortune to be, or we would have had retarded achievements indeed) but in making her career she had need of no such assistance. She owed her first Paris engagement to the goodwill of a charming American singer, Sybil Sanderson, and from then on her career soared, and quite rightly. There was much in her like Fremstad; they seemed always restless and dissatisfied, both women of difficult tempers.”

On 11 December she allowed herself to opine: “My thought of Grace Moore was always of a Broadway singer; a pretty voice and face, but no proper opera foundation, and too pleasure loving to accept the stern discipline that would have made her a better singer.”

On 24 December she notes: I did not listen to Manon. I like Bidu Sayao, but I was busy with other matters. Sometimes a voice does not properly warm up, which may induce off-key strain. The caliber, also, has to do with steady pitch. Some delicate voices like [Lily] Pons often overshoot the mark; there is no support, only the most tenuous of head voice, which means an unreliable pitch if there is the slightest thing wrong with the general condition. Deep breath control is the great essential.”

1948

On 14 January 1948: “Dorothy Kirsten was a protégé of Grace Moore, so I am told, who was very kind to her. Miss Kirsten came here with her manager. I found her a very agreeable young lady; very pretty, a worker and with a fine voice. Not really a theater talent, I would say; she is, however, not at all Broadway, as Moore. I found her sincere and unaffected.” In the same letter she talks about Helen Traubel and segues, “as for Melchior we will not speak of this person, now relegated to the category of radio comic.”

25 April she mentions: “Miss Williams is busy as a bee, always on tour, save for occasional appearances with the New York City Opera. I am fearful that so much travel and work may put an edge on her voice, but we will hope not. She is young and enthusiastic; a good head on her shoulders, and very serious.”

On 26 August she goes back to Helen Traubel: “I heard the Traubel program, and regret the lady’s incursion into true popular music. Also, I note with alarm the emphasis on lower notes, which habit is telling on the uneasy high register. This is not good for a dramatic soprano. In earlier years when she was being bypassed by the MET and sacrificed in a stupid Damrosh opera [The Man Without A Country], Bodanzky, the conductor, argued with me that she had no true dramatic range, the high register not responsive to the demands. I fear I must agree, since later results show this is a marked manner. Up to date, to hear the Traubel voice at its best, one must choose the Immolation Scene with Toscanini.”

On 29 December she again dwells on Mary Garden: “I cannot give you details about Miss Garden; I knew her slightly, but our activities did not merge as is sometimes the case, in benefits or some such ensemble. I was present at the first Pélleas which was a triumph for her and the composer. I have never liked the opera, though I have tried hard to find something in it at various times since. I heard her often in Salomé, a very sensational performance; I would say more from the dramatic than the vocal accomplishment. Hammerstein leaned heavily on her stellar performances and those years that he financed saw many French novelties well worth their production. Nobody was her equal in Thais and Le Jongleur and other typical French roles. She was not a good Carmen but her name was enough to draw forth the crowd. She had fine partners, too, in Muratore and Renaud. Miss Garden is “all” Scot from Aberdeen. There is no Latin or Celt of the more melting kind in her, as far as I knew.”

1949

10 August 1949 finds Farrar recalling: “Gustav Mahler, he was a most sensitive conductor with who I sang a few times at the MET. He was very neurotic, and of uncertain temper and manner. I did not care for his monumental symphonies, and I fancy the fact the he could not measure up to the immortals played no small part in his striving and moods. His blonde wife [Alma], lovely indeed at the time of their marriage, afterward married Franz Werfel; both small men, but they appeared to have some strong attraction for her.”

On 3 September Farrar is in a mood to set the record straight: “A long, sad letter from Lilli’s niece, in solitude at Schartling. She laments, as I would do, fiercely, the insistence on the Max Reinhardt réclame, when the whole musical world knows that the Salzburger Fest was inaugurated by Lilli Lehmann under the patronage of the Archduke Eugen, because he honored her for the great artist she was, with such names as Muck, Mahler, and the opera personnel of the Vienna Oper to sustain the stage and orchestra plan. It makes me angry to note that the charming Bijou Opera House, that is the true home for the Mozart operas, with the Mozarteum for concerts (the cornerstone laid by Lilli herself) should give way to the renovated stables for the Reinhardt plans. The Domplatz will suffer the all too frequent rains, and make performances impossible. The band of mountebanks and inflated poseurs who swoon surrounded Reinhardt with their Broadway moneybags is still a hard mouthful for me to swallow. Ah, well, I am thankful to have memories.”

12 December finds Farrar thinking aloud about the influences of teachers on their pupils: “I do not agree with Mr. Lissfelt [John Frederick, Pittsburgh music critic] re Maggie Teyte. She specializes in French repertoire. For me the voice is brittle, cold and very stylized. A pupil of Jean de Reszke, I had the feeling (as with many of his pupils and those of Marcella Sembrich) that these past masters of song had grafted onto their aspirants the methods by which they had to a certain extent defied time, thus the natural ebullience of a young singer was founded on the older “art,” not the individual spontaneity. Also there is little use for extended range in this genre of French singing, so one never knows if the singers is really endowed with a normal range and dynamics…however this is my personal reaction.”

4 December finds Farrar talking about recordings: “Yes, I have last year’s recording in London of Flagstad with Furtwängler, the finale of Götterdämmerung, a wonderful rendition. They are obtainable here as the London group works with RCA Victor. I have the Welitsch record of Salomé…a good reproduction of the voice, but one must see this primitive creature to enjoy her completely.”

In the same letter she puts on her fashion hat: “Flagstad is a very sweet person, very forthright and natural, not spoiled by her prodigious success. She has no taste in dress, alas, and does not make the most of her fine skin and pretty hair, The style of the usual dress she wears does not flatter her figure She is amply but well proportioned, with small hands and feet, a wholesome figure at all times. She is inclined to drab colors. Her first concert dress was her very best, a sweeping black velvet with a wide lace collar; she looked a picture indeed.”

1951

On 10 January 1951 she excoriates the recent Don Giovanni broadcast 6 January] from the Met [Reiner: Welitsch, Resnik, Conner, Conley, Silveri, Baccaloni]. “I did not care for the Don Giovanni with Reiner, one of my prized operas. The women were all out of line and the conductor greatest at fault. I have such heavenly memories of earlier performances with painstaking care on everyone’s part; delicacy and refined style. The orchestra was definitely coarse in texture. Welitsch still is unequalled in Salomé, to date her best role, but she is sorely undisciplined and does not always sing true. This is carelessness.”

The following week, in her letter of 17 January she talks of the most recent broadcast: “I did not hear the [13 January] Trovatore, the Rigal soprano is nothing to induce me to hear; on the other hand, I note a critic refers in disdain to the mezzo (whom I have liked for her frank, dramatic display and generous voice) [Fedora Barbieri] while praising the soprano to the skies, mentioning her elegance and dignity…she is stiff as cardboard, and has no appeal at all – my opinion – so you see how one can differ.”

The day after she went to New York to hear the 15 February Wednesday matinee performance of Götterdämmerung [in the mid-week Ring cycle] she wrote: “I am too full of the superb Flagstad performance of yesterday to think of much else. The day was fine and the ride in from the country most enjoyable. The matinée lasted five hours with one short entr-acte. The decors were not good. The Rhine looked like a poor edition of the Hudson Palisades, narrow and out of perspective with too much emphasis on the middle stage, rather than down front. This worked badly for the Rhine Maidens and the finale of their singing. The Siegfried Set Svanholm, was excellent, youthful and buoyant, but the great star was, as usual, Flagstad. How this woman pours forth such torrents of purest lyric melody is something we will not hear again. Her classic line and economy of gesture again made the nobility of the role apparent, where others swirl about the stage with much tossing of drapery. I am exhausted, but the harmonies linger with persuasive beauty. I can relive them all with the inner ear. So frantic was the enthusiasm for her that should anyone voice the slightest difference of opinion I am sure he would be mobbed. How easy it is to climb aboard the bandwagon when all is once again safe!” [The last sentence clearly means that by 1951 the controversy about Flagstad and the War and Norway had lifted enough that her performances were praised without political overtones.]

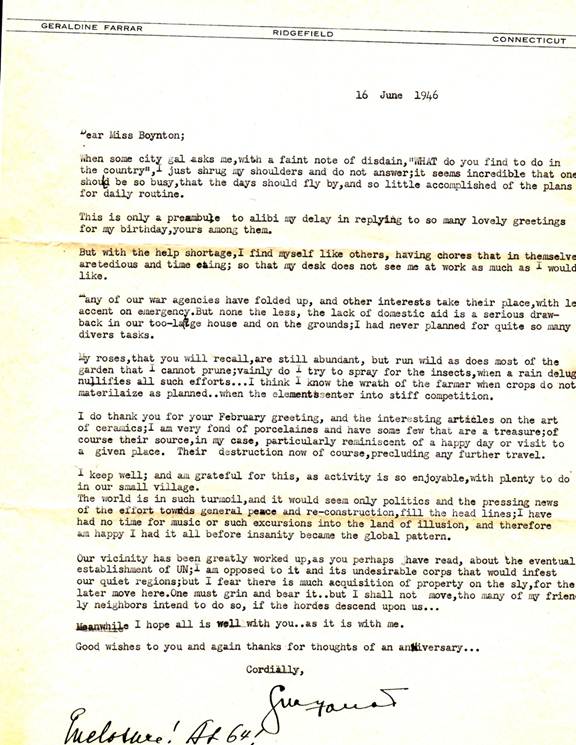

(husband of actress Katherine Cornell, click here to read more about her)

(husband of actress Katherine Cornell, click here to read more about her)

On 5 April she notes: “I heard a beautiful Sunday Symphony; a Wagner program with Eileen Farrell. I have noted this young singer for some time, and she gave a noble account of herself in this offering. She seems to be more of a radio than a concert artiste, but the voice and her use of it, could not be surpassed. However the hour is awkward, 1:00 to 2:30 pm.”

A few weeks later, on 26 April, after all the comments on Flagstad and Farrell she looks back: “I have written about Fremstad, She was cremated and the urn will be taken to her Western home. Her vocal ability was nothing like Flagstad’s. Hers was a mezzo voice of warm color, but not the clarion call of the Flagstad. She worked hard and did accomplish fine effects with the soprano roles of the Wagner operas, but there was always careful preparation for the range that was not hers by nature. Her splendid figure, stately bearing and grace were of the Viking style. Indeed, she was of the great tradition.”

On 3 October she writes, “Hearing Mario Lanza last evening. I could only regret that this fine youthful organ was wasted in yelling over a radio program. He should be studying serious music to become a real singer in opera. A very pleasant chap on the screen, and certainly with vocal potentiality, but the voice will not last long if he continues in the present ear-splitting expenditure of natural clarion-like scale.”

1953

We now jump to 8 December 1953 where Farrar rambles about several singers and items of interest to followers of the Metropolitan: “Tagliavini seems not to be in the company. Bjoerling, I am told, is too fond of his bottle to be a reliable member, though he is announced now and then. Baccaloni must wait, without doubt, for those operas, Barber, Elisir d’amore, etc, where the buffo role is dominant. Miss Munsel after her “Melba” film (which I did not see, so cannot render a verdict, save the observations of English friends who were pretty severe) now seems to be devoting most of her time to her offspring. A recent photograph with it, and recommending some kind of diaper (ad) is the latest addition to the publicity man’s columns. Miss Peters is, by far, the more talented. She is kept busy, and studies hard. I do not know her, only see and hear her on TV. She is pretty and poised. The voice show signs of serious attention, always good and apt to be unusual in these times.” (Farrar must have seen Peters on the Ed Sullivan TV show where she was a frequent guest; I believe she holds the record for number of appearances of an opera singer on that show).

By 19 March 1955 the present vocal scene comes to Farrar’s attention: “A newcomer to the MET is very fine – I’ve known her records for some time, Renata Tebaldi. A pleasure to read that not all critics are immune to fine vocalization allied to dramatic fire.”

On 23 December we now hear Farrar mention Maria Callas: “Mr. Bing has engaged a very fine singer in Tebaldi. I have heard and admired her records only, but the reviews have been excellent and she seems to be in demand. Another is coming to join next year, Maria Callas, a fabulous singer but without the sweet caliber of voice. A fiery person who seems to exult in startling effects. So much the better. These two should stir up some superior interest in music.”

1956

A year later on 1 November 1956, on the same theme: “Mrs. G. [her friend who drove her to New York] and I had planned to go to the Saturday matinee to hear the new star Callas, but she was unable to make the effort. Callas has box office attraction and must be an arresting figure on stage. I have only several records to form a conclusion, not quite so proper as did I hear the living artiste. The voice is brilliant, but there is little beauty in it. The other prima donna, Tebaldi, has a lovely quality. Well, it all makes for interest.”

In her letters Farrar’s operatic interests span the early days of the Twentieth Century through the Tebaldi/Callas era. The letters in the Stotler volume stop in 1958. But she lived another decade and I am sure she kept her interest in operatic happenings through that period, but I have not seen these letters or am aware of her opinions at that time. I was present at the closing of the old Metropolitan Opera House 6 April,1966, and at the beginning of the gala evening several legendary old-time singers took their seats on stage to tumultuous applause (I especially remember the huge hand given to Elisabeth Rethberg, for example, perhaps because she was so beloved and had kept out of the public eye for so long). I forget whether it was Rudolf Bing himself or another master of ceremonies who read two letters of regret that they could not grace the stage that night, Rosa Ponselle and Geraldine Farrar!

Charles Mintzer

BOOK TIP

For those who are interested in the rich library of operatic biographies there is a very helpful 1984 book: Andrew Farkas: OPERA AND CONCERT SINGERS, An Annotated International Bibliography of Books and Pamphlets, 1985, Garland Publishers. Farkas has authored significant books on Jussi Bjoerling, Enrico Caruso, Jr. and Lawrence Tibbett. This title, Ms. Nash’s GERALDINE FARRAR, is listed in the Farkas book and reviewed as to its contents and scope.