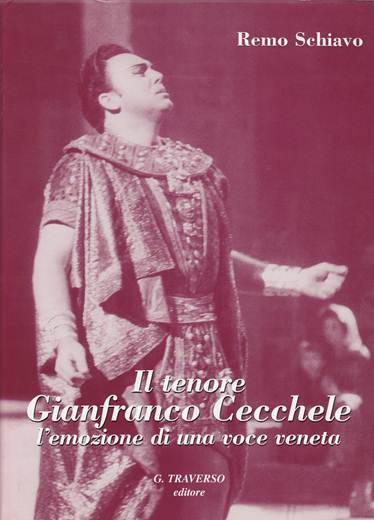

An exclusive interview with the legendary Italian tenor GIANFRANCO CECCHELE

Gianfranco Cècchele’s career was a little bit strange. At first sight one could think that he was crowned before he was king. He made his début in 1964 in Catania and a few months later he already stood on the boards of La Scala in his second opera only. No other tenor had such a meteoric rise unless one thinks of Giuseppe Di Stefano. But Di Stefano profited from the fact that a lot of older colleagues (Gigli, Lauri Volpi, Lugo etc) had showed too much sympathy for the defunct fascist regime and were not welcome at La Scala for a time. On second sight one has to admit that Cècchele too was launched in a period when there was a dearth of lirico spinto tenors. At the end of 1964 Franco Corelli sang his last performances at La Scala (Calaf) and would never return. Mario Del Monaco was no longer young and the voice had lost much of its qualities due to his unrelenting diet of Otellos and the consequences on his health of a car accident that almost cost him his life. Already production values reigned at La Scala and the management didn’t like engaging a rich tenor voice in the diminutive body of Flaviano Labo. Carlo Bergonzi belonged to much to the stand and deliver category and was anyhow not very welcome. And that other young hopeful Bruno Prevedi was notwithstanding his baritone origins more of a heavy lyric tenor than a real spinto. Therefore Cècchele was a godsend as he not only brought the real voice with him but also an athletic figure.

For several years his career blossomed and he did the round of all important Italian theatres, made an American début (Chicago 1966) and was popular at the Verona arena. Only his recording career didn’t take flight (see interview). Somebody (???) published two commercial cassettes with arias from those youthful performances (the tenor says he never knew about them) and they show a healthy blooming and generous Italian spinto with impressive top notes, good breath support though not too subtle in musical interpretation. In his interview the tenor stresses the fact that he didn’t have a vocal crises in 1969 after an impressive diet of heavy parts in Norma, Aida, Turandot, Forza etc; just a chronic tonsillitis. That differs a lot with the interview he gave to Lorenzo Allegri in 1970 after his come back. There he speaks of bad councillors, too many performances and using his vocal cords with brute force. Anyway after surgery he returned to the scene and something had changed. The voice was less smooth, sounded more like Del Monaco than before and some of the youthful sheen had disappeared. But it remained an impressive instrument and he had no problems in continuing his career. In the meantime tenors who started their careers several years before Cècchele had taken their time and were now recognized as the successors of Corelli and Bergonzi. Luciano Pavarotti was not a menace as his roles during the first ten years were limited to a far more lyric repertoire than Cècchele’s. Placido Domingo however was another matter. He belonged to the same voice category as Cècchele as he could switch from lyric to lirico spinto and even to heroic (with less success). The sound of the Spaniard was richer, warmer than Cècchele’s voice and he started to eclipse the Italian tenor. Pavarotti and Domingo got recording contracts which made their name better known. And due to their American experiences they soon understood that Italian was no longer the language of operatic business; so they learned English. Of course two or three top tenors cannot fill the schedule of the most important theatres in the world and there was always room for someone with the great talents of Cècchele. But in his chronology one slowly notes the arrival of interesting theatres which do not aspire to a first or second rank in the pecking order: Sofia, Athens, Bergamo (72), Gelsenkirchen, Constantinople (73), Adria, Marseille (74), Mannheim and Brussels (75). In that last place I heard him for the first time when he sang Tosca at De Munt. He looked the part and had voice to spare in that modestly sized theatre. That was the year too he finally cut his first recital for Cetra. He was clever enough to do a Verdi-recital with pieces from the “anni di galleria” and he did not go for the well-known and much recorded war horses. Still he was a bit unlucky as almost at the same time Bergonzi’s three record Verdi-recital appeared which clearly showed the difference between a very good tenor and a master of Verdi-singing and phrasing (even though Cècchele didn’t sing flat as Bergonzi already did).

In 1976 Cècchele finally made his début at the Met where his career was rather limited (though he doesn’t agree with me on the number of Met performances, the Met records I consulted are clear and perfectly kept). It’s somewhat strange to read in a review of his Michele that he sounded like an underpowered Del Monaco. A bad night maybe as Cècchele proved time and again he could easily fill barns like La Scala and the Verona aria. Anyway with only 25 performances under his belt he had to take his leave from the Met which made his name less than a household one in the important US market. The Met at that time had a number of tenors on its roster who sang more or less the same repertory: Giuseppe Giacomini, Lando Bartolini, Nicola Martinucci, Giorgio Lamberti. Maybe the management thought they could do without Cècchele.

In his interview the tenor too alludes to some record-divi who didn’t like his appearances. Though he doesn’t name anyone specifically we can take it for granted he is thinking of Domingo. Witness the big Scala row that almost wrecked his Italian career and there are some rumours that Domingo was not always a generous colleague in other matters. Someone at CBS once told me Domingo (who recorded a lot for CBS in those years) objected to the production of their Aroldo-recording with Cècchele (a Carnegie live recording with Caballé). After the Scala problems most big Italian theatres followed La Scala’s example and closed their doors for Cècchele which was the luck of many smaller Italian houses or of theatres all over Europe.

I heard him often in my own Flanders in Ghent and Antwerp where otherwise we would have been without such an honest Italian tenor sound. In the eighties big houses with the exception of Vienna and Verona were not interested anymore in the services of the tenor: strange, as in those lean tenor times he could sing rings about most of his colleagues who were let loose in the top notch theatres. Of course his hatred of Regie-Theater was well-known but in traditional productions he would always have been an asset. One often wondered what names like O’Neill or LaScola did in performances and even recordings with an instrument that was better suited to comprimarii roles while Cècchele’s voice was neglected. Even in the nineties his voice was still in good condition as is proven by some later recordings.

Mr. Cècchele was so nice to give us an interesting interview in writing (he typed himself his answers in Italian, cynically noting “I’m becoming a typist at my age). He shows to have a healthy amount of tenor-self-esteem but he is often not shy in calling a spade a spade. We thank him very much for his collaboration, wish him and his loved ones much health (he is now 73) and we can only regret that no modern tenor (Italian and non-Italian) is able to sing the many taxing tenor roles with the vocal splendour and stamina Cècchele had.

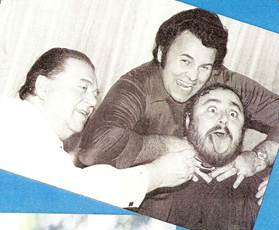

(with Tagliavini and Pavarotti)

(with Tagliavini and Pavarotti)

ON: Please, tell us something about your youth !

GF C: I was born on the 25th of June 1938. That means I still have some vivid war memories. My father was not a soldier anymore as during a march in the rain he became so ill he suffered a terrible bronchitis and was set free. His two brothers were made prisoner of war in Albania. We lived and still live in Galliera Veneta in the North of Italy. There is a magnificent villa which once belonged to the Austrian Empress and which was requisitioned by the German SS. Their commander had an Italian mistress from Trieste and I still remember that beautiful lady as she often visited our home when my aunts knitted and sewed for her. When the Germans finally retreated they indiscriminately shot men, women and even children. My father hid eleven other men in our home and at a certain moment the German commander appeared and forbade everyone to enter while he was waiting for his soldiers, reconnoitring the surroundings. The Germans however didn’t enter and nothing happened.

ON: What did your parents do for a living ?

GF C: My father was a farmer at that time. We had a few cows and calves, 2 pigs, one horse and a lot of chicken and ducks. My mother and my aunts did all the domestic chores.

ON: Was there a radio in you home ?

GF C: Yes there was and we were one of the very few families who had one. Even very young I already was fascinated by the many operas that were broadcasted. I remember the goose bumps I got from certain voices : Gigli, Caruso, Lauri Volpi, Schipa, Pertile, Del Monaco, Gobbi, Ruffo. Great voices could almost be heard every day on radio in those years. We didn’t have records as we didn’t possess a turntable.

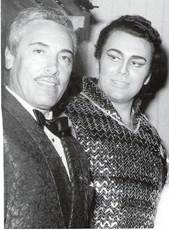

(with Mario Del Monaco)

(with Mario Del Monaco)

ON: At that time there were still a lot of opera movies made, weren’t there ?

GF C: Oh yes. In our region there were a lot of music lovers and we all went to see those movies. I vividly remember Gobbi’s movies. Do not forget that the baritone was born in Bassano Del Grappa; only 15 kilometres further on from where I live. I was much impressed with his movies like Rigoletto (with Pagliughi and Neri), Il Barbiere di Siviglia (with Tagliavini) and Elisir d’Amore etc; ten in all which I now possess on DVD. The gentlemen, who call themselves producers or directors could learn a lot from those movies. By the way, I finally met the baritone in 1972 when he still sang a wonderful Scarpia to my Cavaradossi in Montecarlo and he directed as well.

ON: In your youth Mario Lanza movies were extremely popular

GF C: A magnificent voice (cunningly amplified), a fine figure with an attractive smile in those movies. I always liked those movies and still like them though he sang in a somewhat Americanized Italian. Bravooo !!!!!

ON: Did you ever visit opera performances in those years ?

GF C: Well, there were opera houses in Venezia which is closest to home and there were houses in Padova, Verona and Treviso as well. Still, though I always liked opera in those years (say between 17 and 20) I dreamed to become a professional boxer and I started in the category welter weight (till 78 kilogram). Heavy weight world champion Primo Carnera’s name still resounded and was a great inspiration. I was the strongest boy in our region and I had proved it “forcefully”. In one and a half year I went from category “starters” to “amateurs” as I won two bouts on points and one with KO. At the time the law stipulated that you came of age at 21 and not at 18.Therefore my father had to sign a document that he was responsible in case of “an incident”. He took the piece of paper and burned it. Gloria Finita.

ON: When did you discover your voice ?

GF C: A child that is born with a different or better voice than other children knows it from the start. As a child with a white voice I sang in church and later on I joined the baritone section. I very much liked to imitate Tito Gobbi-Mario Del Monaco-Beniamino Gigli and Claudio Villa, a pop singer though a nice tenorino. My lucky moment arrived during my military service in the Recruit Centre of Avelino in the south of Italy. There was a celebration on a patriotic day and I sang Granada, imitating Mario Lanza. The colonel heard me and gave me a furlough for ten days on condition I went to consult a singing teacher. I knew nobody in the business but a friend gave me the address of the famous soprano Iris Adami Corradetti who lived in Padova, only 35 kilometers from home. She listened to me while I sang Granada, Torna and Recondita armonia. She told me I had a voice of gold but it would take me six or seven years of study for vocal development, score reading etc. That was simply impossible for me as I was already married and we expected a baby. I asked her to write a letter to the colonel with her opinion on my talent. He read it and asked: “ seven years ? you have a voice that penetrates the soul. I’m sure you will be ready in two years. I had my first lesson on my 24th birthday and I made my début 18 months later on the 5th of March 1964: La Zolfara by Giuseppe Mulé at the Teatro Bellini in Catania.

ON: Your teacher was Marcello Del Monaco, brother of. Why did you chose him and what did he teach you ?

GF C: During the celebration of our region’s patron Saint Maria Magdalena I sang my usual songs plus Recondita armonia. Somebody recorded it and my father gave the record to someone of the family (a doctor who is now running a hospital). He studied as a baritone with Marcello Del Monaco. He took me with him and the maestro accepted me. He taught me the Melocchi method; a method Caruso used too though adapted for a voice of a lirico spinto. In a few months time my voice was transformed. The volume increased, the beauty of the timbre was always present and my high notes became secure, a high D flat included. The method asks for a lowered larynx and perpetual diaphragm support; the way Mario Del Monaco sang for the first 18 years of his career. The method suited me admirably but I don’t think it fits the a voice of a lighter lyric tenor. You cannot generalize when teaching and impose a vocal technique on someone as a singer can only can by receiving examples. With Del Monaco I studied vocal technique primarily but I also studied score reading and I got private lessons from Maestro Renato Pastorino from Milano who collaborated with La Scala as well. As to vocal technique I do believe that the passaggio for a tenor depends upon the opera you sing. Technically spoken you can cover on an E flat, an E natural, an F, an Fsharp but you can also sing it open depending on what you want to express with your singing. I have always been a lirico spinto but when I wanted I was able to sing a pianissimo, a smorzato. Of course every voice has its own pianissimo and mine was definitely not Tito Schipa’s while he didn’t possess my generous sound.

ON: Did you listen to recordings of famous predecessors ?

GF C: There is not a single singer who did not and doesn’t listen to recordings by other famous singers since records were first cut. The important thing is to digest it and keep your own personality while modernizing your interpretation.

ON: How long did you study with Del Monaco ? Did he agree with that early début ?

GF C: After seven months I was able to sing Nessun dorma, Celeste Aida and Meco all’altar di Venere and Mè proteggi e mè difendi. I presented myself at the singing contest of the Teatro Nuovo di Milano and sang these four pieces. The general manager asked me who my maestro was en gave a phone call to Marcello Del Monaco. He wanted me to make an immediate début in Un Ballo which I would have to study with his company. He passed me the phone and Maestro Marcello said “Don’t accept”. Well that was not necessary as I had already decided not to accept. I only participated in the contest to assure myself that my voice was different from everybody else. I knew I was not ready to sing a complete opera and I returned to Maestro Marcello. All in all I studied for three years with him. Then I discovered that my vocal means were different than Mario Del Monaco’s as I could easily pass from lyric to lirico spinto and later to heroic tenor. Thus: Butterfly, Pagliacci, Traviata, Otello, Chénier, Adriana etc. etc. My voice was longer than colleague Mario’s. I could sing a high D which he couldn’t. It is true there are some parallels in our voices like they were with Gigli-Tagliavini and Di Stefano-Carreras. The voices may have something in common but the interpretations often widely differ.

ON: How was your début ?

GF C: La Zolfara was my first opera and I didn’t have to fear other tenors as there existed no recordings. I was paid 175.000 lire (ON = the monthly salary of a white collar worker at the time) per evening for three performances; hotel and travel fare also paid for. Money I could well use at the time. Rehearsals lasted 18 days. I found the role rather easy and I couldn’t really show my vocal capacities. To be honest I didn’t like the opera. I was not nervous and I have never been during my career. Musical difficulties have to be resolved while studying the score and not on the scene. It’s like boxing. During your training you resolve your problems of endurance.

ON: And then came La Scala ?

GF C: After La Zolfara I did a few auditions and immediately got some contracts as the Italian operatic world was always on the lookout for new talent and everybody had gotten wind of a new tenor. So in June 1964 I sang my second opera on the stage of La Scala. I made my local début in the role of Adriano Colonna in Wagner’s Rienzi; a role originally written for a mezzo soprano. Mario Del Monaco should have sung the title role but he declined (ON: Del Monaco was still suffering from the consequences of a grave car accident). So Di Stefano accepted the role and had more than an hour of music cut. I was very sorry that my part too lost some 18 minutes of music. After the premiere I was asked in the office and Luigi Oldano proposed the role of Pollione in Norma for the next La Scala season. My first roles in those years were Pollione, Radames, Ernani, Calaf, Don Alvaro. I wouldn’t advise those roles to my pupils if they don’t have the vocal weight and are lirico leggieri or when they are slightly built and cannot recuperate quickly after such a role.

ON: Why did they ask you in 1965 for the Paris performances of Norma with Callas ?

GF C: Initially Del Monaco would have sung those performances but he got to know that her lover Onassis had “prepared” the theatre to receive La Divina in a worthy way and he refused to honour the contract. The Paris Opéra all at once was without a tenor and asked for the help of La Scala and they gave my name. I was very much moved to meet and to sing with such a celebrity. At the first recital I sang my romanza which she listened to and then told conductor George Prêtre: “at last a new tenor is born”. The rest is history.

ON: Your chronology mentions a few recording sessions with Decca though as far as I know no recordings ever appeared on that label.

GF C: After those Paris Normas I signed a contract with Decca where at the time Mario Del Monaco was one of their exclusive artists. They proposed a complete opera (title to be discussed) and two records of arias. My English was not too best and I was not aware of a clause that stipulated the contract was valid for five years with the possibility for Decca to renew it for another five years on condition that I could record only if Mario Del Monaco refused to make these recordings. He did not and in reality this was a system to prevent me to make records. I had two different proof sessions though always with the same technicians for whom nothing ever was OK. I lost patience and wished them to hell. It was not possible to have the contract resolved and I lost ten years as a recording artist. Nice people, don’t you think ? Afterwards I recorded La Vestale for Bongiovanni and in the series “Il mito dell’Opera" there is a recital by me with 21 arias.

ON: You have a big family. Wasn’t that a hindrance for a world career ?

GF C: God has given me three big gifts: the voice, a good musical memory and the greatest gift of them all: a wonderful wife who gave me three sons and two daughters. At this moment I’ve got already eight grandchildren. Therefore I don’t miss the theatre anymore. But it is not true that for familial reasons I preferred to sing in Italy. After the Paris Norma of 1965 I sang Ernani and Simon Boccanegra in Bilbao, Oviedo, Barcelona and in Vienna I sang at least 16 performances a year.

ON: You sang La Gioconda with Tebaldi in Naples, her last Italian performances.

GF C: That’s my only artistic regret. When my career started to blossom Maria Callas, Renata Tebaldi, Giulietta Simionato, Cornell McNeil, Aldo Protti, GianGiacomo Guelfi were winding down theirs. But this is the parabola of life.

ON: How was the artistic relationship with Karajan ?

GF C: Herbert von Karajan was a wonderful conductor. I’m very sorry that due to our different contracts we couldn’t collaborate more. He showed himself to be very respective and what a scrupulous musician he was. During the first rehearsal for our Cavalleria Rusticana at La Scala I sang in one breath with a fine legatura:” E nun me mporta si ce moro accisu e s’iddiu muoru e vaju mparaddisu”. The tempo was broad with a vocal crescendo on an A flat. He asked me:” are you sure you can sing it that way at the performance ?” “Yes” I replied. “100% sure ?” “Yes” I repeated. “Very well, phenomenal” and he took his score and drew a long bow in it to communicate it to the harp and the rest of the orchestra. It is true that normally Bergonzi would have sung those Cavallerias but Karajan had been present at my La Scala Aidas and he was probably already casting the roles for the movie he would later produce. Therefore he preferred me as my sound was more muscular and I looked better in the role as well.

ON: What caused your vocal crises in 1969 ?

GF C: I never ever had a vocal crises. I had chronic tonsillitis which did permit me to sing as well as I used to while some high notes didn’t pass well. I decided to have surgery. I came back as Arrigo in a Vespri Siciliani with Maestro Thomas Schippers for RAI and then sang early 1970 several performances of Cavalleria at La Scala. And I never stopped and looked back. Ah gossip !!!! And no I didn’t change my vocal technique and never had problems while growing older. I have sung on the scene till my last performance (Pagliacci in November 2005) at the Teatro Sociale in Rovigo and then continued giving concerts till the end of 2008. I didn’t stop for vocal problems but I had troubles with my coronary artery (I’ve got 4 medical stents).

ON: Which were your heaviest roles ?

GF C: I had a repertory of 41 roles. Some heavier than others. Vespri Siciliani is more difficult than Tosca, Aida is heavier than Traviata, Otello is more difficult than Butterfly and Andrea Chénier heavier than Turiddu etc. But as I have said before you have to study the role thoroughly and resolve all the problems while studying and not while singing on the scene Usually I needed 5 of 6 days depending upon the length of the role of intense study to master musically a role. But having it in my throat, overcoming all vocal difficulties could take much longer.

ON: What were you paid ?

GF C: Now this is what I call an indiscrete question. I can only say that for the moment I live in a villa with 15 rooms and 5 bathrooms, three garages and a garden of 22.000 square metres. I have given each of my children a place to live and I have always paid my taxes.

ON: How did you prepare for a performance ?

GF C: I’ve always lead a normal life and on a day of a performance I didn’t shut my mouth but spoke normally. Five hours before a performance I would eat a plate of spaghetti with tomato sauce and an apple. I drank one glass only of red wine and drank a lot of water without gas. Two hours before a performance I was in the theatre and started warming up the voice. I always slept well the night before a performance but bad after I had sung as I was always mentally trying to correct the mistakes I had made. I always put everything myself in my suitcases but my wife unpacked them. I don’t think I would have a different career without my wife but my life would have been far more unhappy. It is a joy when one has sung well to share these moments with the person you love.

ON: Why was your Met career so short ? Only 25 performances.

GF C: The interviewer is wrong on the number of performances. In 1978 I participated in the Metropolitan tour and I sang 14 times Cavalleria and Butterfly in 14 different cities. Somewhat later there was a change in the management and it didn’t rehire me as I was annoying some record stars while I didn’t have the support of record companies.

ON: What happened at La Scala in 1981 ? And what were the consequences ?

GF C: Normally I would have sung a number of performances of Cavalleria Rusticana. But there was pressure on them to annul my contract so that Domingo could take over while at the same time his complete recording of Cavalleria-Pagliacci could be presented. La Scala was very rude to me as I refused the manoeuvre and La Scala declared that “I was not suited for the role”. I didn’t’ take it lightly and it all ended with a law suit. Ten years later La Scala had to pay me 268.000.000 millions of lire (ON: 250.000 Euros) in damages. But they asked all other 13 Italian Enti Autonomi not to engage me anymore. The only places in Italy that still hired me were the Verona Arena and the Rome opera. Evidently, they needed a voice like mine for their performances. (ON: Cècchele was invited back at La Scala for one performance of Tosca in February 1989).

ON: How were your relations with conductors ?

GF C: I was lucky. My career started in the most important opera theatres where the best conductors worked. I picked up a lot with them. Good conductors know and respect operatic traditions which were accepted by the composers themselves. They offer singers a choice so that they can choose the version that is best adapted to their vocal means. A lot of composers jotted down alternative versions in their scores and often noted that the orchestra should be a real help so that the singer can build a character with his musical interpretation. Singing is the most important aspect of opera and pieces are written for singers, for voices. If one doesn’t agree, one can always perform orchestral pieces or chamber music. I simply do not get the MUSICAL DICTATORSHIP of maestro Muti. Yes, I always had a tempestuous relationship with him when he though his tempi were perfect, when he didn’t take into account the qualities of the available voices.

ON: What is the reason for the decline of opera in Italy ?

GF C: In Italy ? In the whole world my dear interviewer !!! Too many crazy and incomprehensible productions. Who is interested in a Norma with tanks on the scene ? Nobody unless a few war crazies. A Traviata with a lot of heroine prostitutes has nothing to do with the opera while producers nevertheless and desperately try to put it in our own time. WHY ? is it better when one updates everything ? Shame!!! I remember my refusal to do an erotic scene in Pagliacci in Germany. I had to simulate sexual intercourse with a nude Nedda bound on a cross. Other tenors had sung the first performances and then I arrived for three evenings. I said no to that scene and the theatre didn’t have enough time to find substitutes for the two remaining performances to act these vulgarities , certainly not wanted by the composer. After the first one they paid my fee, travel and hotel costs and proposed Tosca instead of Pagliacci. I refused to comply with the wishes of those dudes.

ON: What’s your opinion on today’s tenors ?

GD C: Each age has its tenors and if they are good I shall applaud them. But nowadays I’m dead tired of hearing “NEMORINO A TEBE”

ON: Were they roles you regret you didn’t sing ?

GF C: Theatres often proposed roles I would have sung if I had found the time to study them: Un Ballo, Sansone e Dalila, Isabeau, Rigoletto, Lucia di Lammermoor. Yes I did and could sing lyric roles like Alfredo whom I sang often. I made my début in the role at the arena. You tell me you were there and didn’t think it the best of my roles but the reviews were very fine, even it is not my favourite opera.

(with Franco Corelli)

(with Franco Corelli)

ON: Which theatre did you like best ?

GF C: I always felt well in every theatre I have sung with one exception. The one theatre where it was often not very amusing to work was La Scala. There was a different atmosphere. They always looked down on you as if they had to protect and guard a heavenly heritage. You had always to keep in mind what an honour it was to sing in the best theatre in the world.

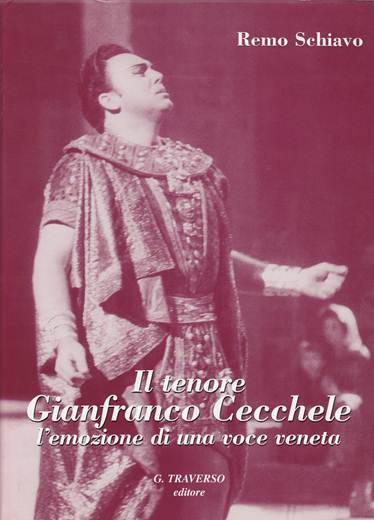

ON: What do you think of the big book on your career and your life by Remo Schiavo ?

It is well researched, has splendid photographs (Editore G.Traverso) but shows some annoying mistakes in the chronology.

GF C: Well, in Italy we say “you don’t look into the snout of a given horse”. I didn’t ask the author to write this book but in my opinion he did well even if there may be a few mistakes. He not only speaks of my career and successes but mentions the sacrifices as well. He gave me 30 copies in return for my compliance with his book and if I want another one I have to buy it even though I get a small discount.

(all these cd's are available through Bongiavanni)

(all these cd's are available through Bongiavanni)

ON: Nowadays you teach a lot of the time

GF C: Yes I do. There is nothing more satisfying than saving a voice that was going to ruin due to wrong lessons. I am happy when I look at the joy in the face of the student whose vocal health is restored so that he or she can finally start working on musical interpretation without vocal trouble.

Jan Neckers