Giuseppe CAMPORA, book review

Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona, Album della Stanza - due

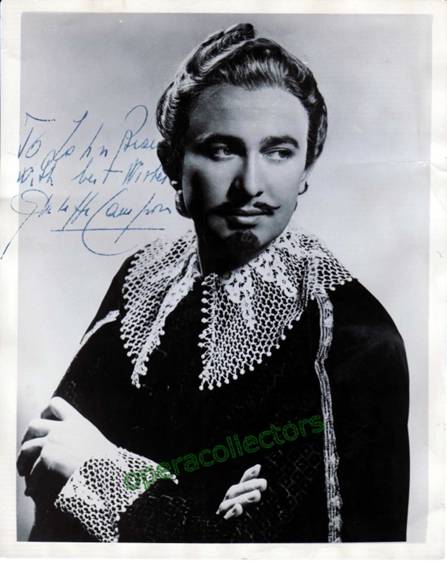

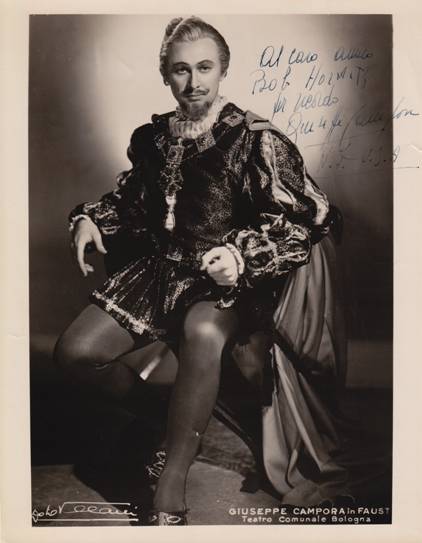

(photos courtesy Charles Mintzer)

Will they ever learn it ? Probably not. Italians and Frenchmen can be extremely loquacious and their academic papers are often crammed with meticulous details on infinite subjects. But no one will ever descend from heaven and (with a few exceptions) write a good book on famous singers. Those books are mainly the works of star studded hagiographers, witness the shabby products by Mrs. Boagno on Corelli and Bastianini in the bad series of singers by Azali Editori. Titles are mouth watering until you take a look at the contents; riddled with mistakes, completely uncritical towards the subject, believing everything what was written in newspaper clippings while half the book is devoted to lovely tributes from colleagues who during their active career tried to stick as many knives as possible into the back of their “caro Franco, cara Giulietta etc.” If one is lucky there is one redeeming feature in those books: often a good chronology and discography.

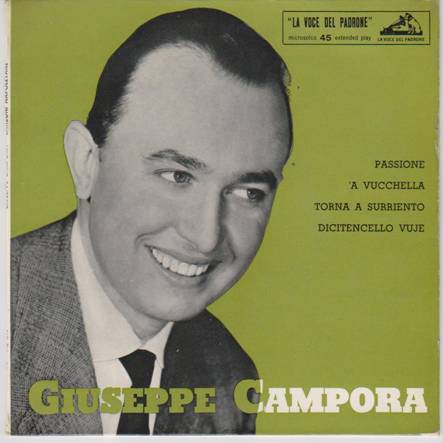

Some books on Italian singers are a prime example of “campanilismo” (the local belfry tower). Italians are first and foremost inhabitants of their village or city (or even quarter of a city) and they are Italians only when the azurri (the national soccer team) play. Therefore it is quite normal that one or another local bank publishes the biography of a local hero, often including singers who have become almost anonymous citizens in their own neighbourhood while still interesting to vocal buffs all over the globe. Of course those books are not easy to be found as they do not pop up in the normal book circuit. World-renowned tenors like Flaviano Labo and Gianfranco Cecchele got an interesting biography but it can take ages before you get your hand on a copy. The editor himself had to put all his notable energy and well known killershark mentality into the task of trying to get his hands on the Giuseppe Campora biography under review. It was published in 2006 in a series called “Projetto La Stanza della Memoria, fototeca per una città.” by the Cassa di Risparmio (Savings Bank) di Tortona. Tortona is a very small city in Piemonte, the North-Western corner of Italy. It is somewhat of a contradiction that a Campora biography belongs to “the memory room of Tortona” as the tenor sang a few concerts in his home town but never even one single opera performance. But he clocked 90 performances at the Met alone and he starred in many performances in Chicago, Newark, Hartford etc. Still someone at the Cassa realized that Campora’s memory is better known in the US than in Italy and therefore the interesting “ritratto di una artista” by Giancarlo Landini is to be found in English translation as “Portrait of an artist”. But why, oh why is the even more interesting biographical section on the tenor’s life not included ? as a lot of basic facts are only to be found in these 13 pages. The chronology of Campora is by the well known Gilberto Starone and it seems to be rather complete and fascinating for cast readers as myself though it is not always accurate. By now Starone should know that Campora did not make his foreign début in 1949 in the non-existing “Opéra Royal Flamand” in Antwerp. Dutch is the language of the land and there has never been “an Opéra Flamand”. It always was the Koninlijke Vlaamse Opera. And Campora didn’t sing Lucia with Gianna D’Angelo in 1965 in New Orleans. Starone for once cannot give an exact date for obvious reasons as the performance took place in December 1962 and is still known as the local début of Placido Domingo in the small role of Arturo. And the Elisir with Peters in Hartford was on Saturday the 26th of 1975 and not on Monday the 28th.The discography seems to be very complete as well as it includes all pirate issues and some mouth-watering live items which up to now have not appeared on CD or DVD. One small carping: the book mentions a 45 giri record with Torna a Surriento and Dicitencello Vuje and doesn’t mention that the record also includes Passione and A Vucchella.

Campora was born in Tortona on the 30th of September 1923. The family was not rich as the mother did her homework and father Campora was a labourer. Sister Sylvana worked in a tobacco factory. Music for those people didn’t mean expensive records, or a private radio an definitely not concerts or performances. Music was best made oneself and with Campora it started as it did with so many good Italian singers: in church. Another possibility was performing with an amateur company and there Campora learned to appreciate operetta which he as one of the few Italian tenors of his time would sing (and record on Cetra). The book only mentions once “pieno Regime, tempi difficili” but doesn’t expand on those difficult times during the Regime. Among the many photographs there is one of Campora with a large group of boys in the Balilla (the Fascist Youth Movement). Campora is one of the few kids not in uniform but as a school boy he undoubtedly had to sing “Giovinezza” (in the third Mussolini-adoring version recorded by Gigli) or the “Inno al Duce” (with new lyrics for Puccini’s Inno a Roma). In his amateur days Campora got his first voice and music lessons. I don’t know why he didn’t become a soldier during the war as he had the right age. In a small town like Tortona (less than 20.000 inhabitants at the time) a young fresh tenor voice would soon be noticed but Campora had stiff competition. A local truck driver had a real dramatic tenor voice and though completely unschooled was the more popular: Primo Zambruno who only at 37 took the risk of an operatic début in 1951 (Timaclub produced an interesting Zambruno CD) and whose international career therefore was rather short. After the war Campora studied privately with two maestri for 4 years while at the same time working as a railway policeman and fulfilling his military service. In the meantime he had already made his début at the well known Teatro Petruzelli in Bari, replacing an ailing Galliano Masini in La Bohème . Continuing his studies he performed in Lucia, Tosca, Bohème, Rigoletto and Butterfly in smaller provincial theatres with other young singers in 1948. The names of some of his partners still ring a bell: Franca Duval, Maria Marcucci, Ugo Savarese, Tatiana Menotti. In those singer rich times nobody would have dreamed of offering a début to a completely unknown and untested singer at the opening of La Scala as happened recently. From 1949 on the Campora career takes flight. The theatres become bigger (Communale Modena, Teatro Grande Brescia, Teatro Verdi Trieste) and so are the names of his partners (Zeani, Panerai, Fineschi, Barbato, Manachinni, Favero, Petrella, Bechi). The “Portrait of an Artist” rightly tells us of those happy times when “lirica” was still the most popular music in Italy, when simple people could recite all the lines from the famous “romanze”, when a young talented tenor could easily rise above his humble station and earn a lot of money. As Campora sang in good provincial opera houses he concentrated on the iron repertoire for which his lyrical voice was so apt. In 1950 that meant a dose of Butterfly, Tosca, Faust, Mefistofele, Rigoletto, Traviata. In those days with less government subsidies local houses couldn’t perform less hackneyed pieces which were already often done at La Scala or the Rome Opera where at the end of the year Campora made his début in Mussorgsky’s Sorocinsky (with Boris Christoff). It earned him the right to return in 1951 in bread and butter operas like Bohème (with Olivero) or Traviata. In the summer of that year he got his first taste of recording when Decca invited him to sing the tenor leads together with Tebaldi in their now historic productions of Butterfly and Tosca. He was now so well-known that he was invited for the famous Brazil tour where he sang performances of Bohème and Traviata with Tebaldi. During the tour he got to know better the other artists like Christoff, baritone Paolo Silveri, the tenor Salvatore Puma and the American soprano Mary Callas. Campora was one of the singers in the famous concert where open enmity broke out between Callas and Tebaldi. 1952 sees Campora’s big break. In February he makes his début at La Scala (though like Carlo Bergonzi one year later) in a world première of a now forgotten work; Rocca’s L’Uragano. Probably the Scala contract was signed several months before Campora’s world renown. Indeed, in that same month Decca launches the recordings made in the summer of 1951. Up to that moment some Columbia-, RCA- and Cetra-sets monopolize the new LP market but now Decca-London makes it appearance with spectacular good sound and an even more spectacular young and fresh couple Tebaldi-Campora. Even a severe critic like Louis Migliorini in Opera News is swayed around. “Campora sounds like a young Gigli but with better taste” is his verdict on the tenor’s Pinkerton. In the recording opera buffs get their first taste of the new tenor. He has the goods: the voice is warm, fresh, very “simpatico”, it has ring above the stave and a nice vibrato. The voice on record sounds full and adapts well to the mike and it comes as a surprise that Giancarlo Landini in his astute essay calls it “light lyric” and not fully suited to the repertoire Campora was singing. Piano too is not Campora’s forte and some people will soon object to the inbuilt tear in the voice. Landini finds another weak spot in Campora’s chain mail though this is indeed easy to find with historical hindsight. The tenor from Tortona has a generic style. He is at his best in Puccini but he sings Verdi, Donizetti and later on Bellini, Rossini and Gounod as if they are contemporaries of the maestro from Lucca. Landini tells us that at that stage of his career Campora couldn’t have sung Radames in a big theatre but he still sounds fine and sings beautifully in the 1952 colour spectacular of Aida where he and Tebaldi lend their voices to Sofia Loren and Co. I remember well how impressed I was when I first saw and heard it. Only a repeated hearing twenty years later revealed the savage cuts made by the director in every duet so that this movie has now become unpalatable. One week after the Aida he performs with Maria Callas for the first time; a Traviata in Catania. During the summer he gets another Italian consecration: performances of Traviata (with Olivero/Callas) and Gioconda at the Verona arena; still an Italian institution at the time and not conquered by hordes of tourists. With almost the Verona cast he records Gioconda for Urania and ads Forza for the same label to his recording list. With Rosetta Noli he puts Traviata on vinyl for Remington. And then his career stalls.

His engagements for the next two years reveal that he is one of the leading Italian tenors but not one of the contenders for the very top; a distinction that belongs too Mario Del Monaco, Giuseppe Di Stefano and Ferruccio Tagliavini. True, Campora performs only at the big Italian houses like La Scala (Adriana with Tebaldi), San Carlo (La Bohème with Jurinac) etc. He stars in Mexico and Buenos Aires as well but there are engagements too in roles which no top dog will accept: Busoni’s Turandot, Jacopo Napoli’s I Pescatori. RAI is happy to recrute him for many a one radio performance of unknown operas like Rossini’s Elisabetta, Glinka’s Life for the Czar. Of course Campora doesn’t realize at the time that many a RAI performance will find its way to (pirate) LP and CD and keep his name well known before the opera public. He is probably embittered when he realizes that his regular recording days too are already over when Mario Del Monaco leaves Voce del Padrone and is cast by Decca/London in roles for which his voice is not always suited (Rigoletto which is in Campora’s repertoire). The discography doesn’t give dates for his one solo Decca recital. So it is not clear whether it was recorded at the end of the Butterfly/Tosca sessions (it has the same orchestra and conductor) or was a recital compensation as often happened with Decca for the arrival of Mario Del Monaco. The two duets with Rosetta Noli recorded in Switzerland too still need a correct recording date.

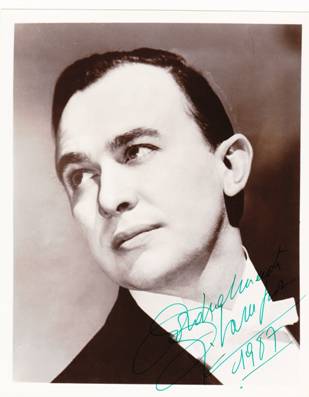

In 1955 Campora gets a career boost when he is engaged at the Met. He starts with Bohème (Tebaldi) and Tosca (Tebaldi/Milanov). Irving Kolodin in his “The Metropolitan Opera” appreciates Campora’s Rodolfo but is severe for his Cavaradossi stating that the tenor “who sang himself out sooner than he might otherwise in a futile effort to justify his use in such a role in a Metropolitan-sized auditorium.” It comes as a surprise that Campora is often asked to sing Faust, Manon (De los Angeles) as well; roles which he has to sing in the original French. In the big barn of the Met Campora is a useful addition to the ranks but he doesn’t’ make a lasting impression. Kolodin further uses words like “pleasant” or “not memorable” (exactly the words our great contributor Charles Mintzer uses when speaking of the tenor). Campora is a popular partner with the great stars, probably because he doesn’t try to upstage them and cannot swamp them in decibels. Therefore the Met often casts him together with their great female stars like Tebaldi and Callas. The tenor is in the Lucia cast where Callas and baritone Enzo Sordello clash and the baritone is fired at the soprano’s request. Photographs reveal Campora to be a slender good looking man, not very tall (1 m. 70) but acceptable and with an eternal smile, singing all the time the same 10 popular roles. For almost 4 years his career is limited to the Met, San Francisco, Hartford (where he will often perform) and the American hemisphere. His easy charm makes him a success with the ladies and in 1955 he marries the Italo-American Franca Nespoli in Mexico. The couple has one daughter: Daniela but the wedding will end in divorce. In 1971 the tenor once more meets Rina Nicrosini, a former sweetheart and by 1974 the two are living together. He marries her in the US in 1983; a marriage not valid in Italy where his divorce is only recognized in 1991. One year later Campora celebrates an Italian wedding at last. Many a singer’s biography suffers from the fact he or she is still alive and doesn’t want private information revealed in a book. Nor do they appreciate even kind criticism of their art: questions which are honestly discussed in the book under review as Campora had died two years before its publication. During his American years Campora only performs a Lorenzo Perosi oratorium (the priest-composer himself is a Tortonese) at La Scala though he finally gets once more in the cast of an important recording with Gobbi, De los Angeles and Christoff. Probably he gets the role of Gabriele Adorno, new to his repertoire, because he is a good score reader and Di Stefano and Björling cannot be bothered to learn the role just for this occasion. Campora also studies the role of Flammen for a RAI-performance of Mascagni’s Lodoletta; part of his artistic heritage as this is still the best recording (since long on LP and CD) among the contenders. His engagements at the Met end in November 1958 and the book states that it is not clear why the opera house doesn’t renew Campora’s contract. In the archives of the Met our brave editor discovered a letter by Campora denouncing Mario Del Monaco in ugly words. It’s probable general manager Bing told Del Monaco of the snitch who had an attack of “jalousie de metier” and maybe the more famous tenor told Bing that the big Met was too small a place for the two tenors. As Bergonzi was coming into his own and Bing still had Barioni, Fernandi and Morell for the Campora repertoire the tenor from Tortona wouldn’t be sorely missed.

Nor did Campora miss the Met as in 1959 he once more took up engagements in Italy at La Scala (Bohème with Scotto), Canada, Guatemala, Britain and the US. Next year he made headlines as he was chosen to sing and act in the television performance of Francesca da Rimini on RAI (Marcella Pobbe) and this at a time when there were only two public channels. Campora looks splendid in the video and sings with his usual warmth and charm; a very believable Paolo. At the end of the year he sings once more the tenor hero in another performance on national television: Tonio in a heavily cut Italian version of La Fille du regiment”. It is clear that Campora has some inkling that his career notwithstanding his two tv-performances needs rethinking. Invitations from the real big theatres for the bread and butter repertory do not come in as easy as before and the tenor sets on another course. The voice is still fine but the competition is even more formidable than when he started out. Franco Corelli, Carlo Bergonzi, Flaviano Labo, Alfredo Kraus, Giuseppe Zampieri, Doro Antoniolo, Bruno Prevedi, Carlo Del Monte, Angelo Lo Forese, Nicola Filacuridi, Antonio Gallié, Angelo Mori, Ferrando Ferrari, Gastone Limarilli, Nicola Tagger, Gianni Raimondi, Piero Miranda Ferraro, Renato Cioni, Luigi Ottolini, Augusto Vicentini, Ruggero Bondini, Luciano Saldari, etc. take up a lot of place on the Italian scenes while Campora’s contemporaries (as singers, not always in age) like Turrini, Borso, Filippeschi, Poggi,Tagliavini, Di Stefano, Del Monaco continue their career. Campora finds a solution. He is available at RAI and opera houses for roles no top tenor easily accepts as they are too modern or take too much time to learn for a single performance while managements are glad that at least one well known name with a real tenor sound agrees to sing often difficult or unknown music. Unknowing to himself at the time Campora builds further his impressive heritage as a lot of those rare performances will find its way on CD or on the exchange lists between collectors. At RAI he sings Donati’s Corradino lo Svevo and Sonzogno’s Regina Uliva. In San Remo he performs a selection of Zandonai’s neglected Conchita; still the only existing recording and at La Scala he is welcomed back as Orombello in a production mounted for La Stupenda Sutherland in Beatrice di Tenda, virtually unknown at the time. And he returns to an old love: operetta. At RAI he is the tenor hero in selections from Paganini and Czardasfürstin and this leads to several engagements as the Italian tenor Alfredo in a lot of performances of Die Fledermaus in the Rome Opera or the San Carlo where he also sings Orphée in Offenbach’s Orphée aux enfers. He mixes these roles with his customary Tosca’s, Butterfly’s or Traviata’s. By 1964 he definitely sings unhackneyed repertoire for an Italian tenor: Offenbach’s Périchole and even more strange, Bacchus in Ariadne auf Naxos (in Italian) followed by a long series of Lehar’s Das Land des Lächelns in Bregenz (in German). At the Met he is welcomed back twice but only for one performance: Faust in 1963 (“in vocal straits” reports Kolodin) and Simon Boccanegra in 1965 (“by force as a dramatic tenor what he could no longer sustain by art as a lyric tenor” is the scathing Kolodin review). Probably he was called in at the last minute to substitute for an ailing colleague. There his Met career ends and he definitely goes for the heavier repertoire like Turandot , Aida while at the same time he continues with rarely performed operas as Henze’s Der junge Lord (Rome), Wolf-Ferrari’s La Vedova Scaltra (San Carlo). At the same time he is at RAI for operetta recordings which later on appear on Cetra. The same label brings out a RAI-performance of Zaza with Clara Petrella (version without chorus) and what a pity it is. More than half an hour of music is cut, included Milio’s aria “E un riso gentil”. This 1969 recording proves that the voice is still there and sounds unimpaired. At a Newark performance two years later Campora is still a splendid Loris in Fedora (Olivero). He continues his career with a mix of the rare and the well-known: a series of Elemer (Arabella) at La Scala, Lord Saville, Nicoletto (Le Astuzie Femminili), Renzo (I Promessi Sposi). At La Scala he returns for the last time in 1972 (Butterfly). As every older tenor he gives a lots of concerts and often includes German lieder by Brahms, Strauss and Schumann. His career starts to halt in 1974 when he has no engagements during the second half of the year. From now on there are often only 6 performances a year though he still adds new roles to his repertoire like Canio and even Oronte for one performance in a small Dutch theatre. At the end of 1981 it’s over though he cannot really take his farewell. Three years later he is back for a few concerts and in 1986 the 63 year old tenor sings an Ernani new to him, probably with some pupils in the hall of the Verdi Conservatory in Milan. His last recorded performance is as Alfredo in July 1990. Then he quietly retires to his home town where he does some teaching. His last years were probably not very pleasant as the book speaks of “long illness, which he bore with serenity” and the photographs show us an emaciated Campora, difficult to recognize. The tenor dies, aged 81, in his home town on the 4th of December 2004. In these tenor poor times his name still lives on as a prime example of the good Italian tenor we now so severely lack. Campora was not a prodigy like Corelli or Del Monaco but the talent is there for everybody to hear. And he himself would probably be surprised to learn his name still sells. There is one CD on Bongiovanni’s Il Mito dell’ Opera and Preiser already brought out a second Campora CD in its well known series.

Jan Neckers