FRANCO CORELLI & a Revolution in Singing, volume 1 by Stefan Zucker

384 pages, New York Belcanto Society (= Mr. Zucker) USA $34.95

Click here to order the book on amazon

Author, publisher and editor -all rolled in one- announces this book as part of three volumes which discuss the evolution of 200 years of tenor singing. Now don’t expect a spun out story full of an internal logic which leads from the times of Nourrit to the emergence of Calleja, Florez or Kaufmann. In reality Mr. Zucker tries by hook and by crook to sell the pirated CD’s and DVD’s he produces. Hence, the 34 pages entirely devoted to his commercial catalogue (pages 322 -356). By crook too is the advertisement on the sleeve that announces “Robert Tuggle, Director of The Metropolitan Opera Archives, contributes a chapter on Björling to the appendices”. This “chapter” consists of a grand total of 49 lines concentrating on the tenor’s fees at the Met and in which Tuggle proves that Bjorling was the supreme tenor of his time, in America at least, proven by his fees compared to other tenors and singers at the Met.

I am fairly confident Mr. Tuggle will not be too happy with Mr. Zucker trying to sell his book by implying that a serious researcher contributed “a chapter” on Björling. Another feature (surely well-known to members of Opera-L) is Mr. Zucker’s penchant for titillating sex stories. Up to now few or any opera lovers at all had Mr. Zucker’s eagle eyes which lead him to write in a caption for a well-known innocent photograph of Del Monaco and Caniglia after a performance of Chénier: “Did he really sing with his genitals in that position ?” The second volume in this series surely promises to be most interesting as Mr. Zuckers promotes this book-to-be-published with a so-called Franco Corelli quote: “People assume that in old age I am hearing Verdi and Puccini in my mind’s ear. No! The music I am hearing and that keeps me going is the sound of Teresa Zylis-Gara having orgasms. “

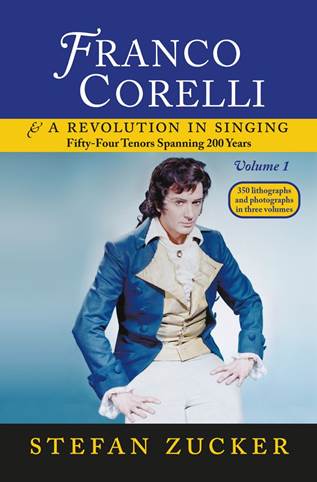

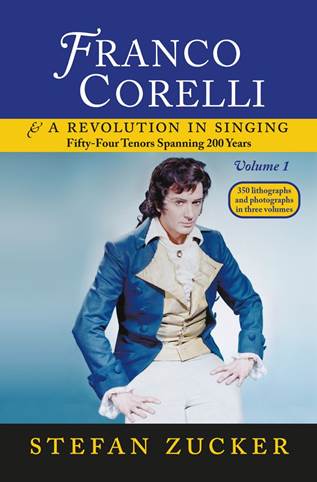

The book’s glamorous cover photograph has Franco Corelli in theatre costume ( Werther) and according to Zucker was made in 1986. Corelli didn’t age well as proven by several photographs taken of the tenor during the eighties. Therefore I’m convinced that Zucker knew this is a publicity photograph taken many years earlier and the year is misleading. But so is the premise of the whole book. The title sleazily implies Corelli was responsible for a revolution in singing which is not true as Zucker and Corelli both heartily admit. “Duprez and his kind of revolution” (from falsetto to chest notes in the high register) or “Caruso and the revolution in singing” (from sweetness to volume) would have been more honest. But then Mr. Zucker couldn’t mine Corelli’s presence in the early nineties during his radio shows. He already sells those conversations on many DVD’s and CD’s and has now decided it’s time to use the tapes in book format as well. The author even publishes the questions (name of the caller included) some not too well informed enthusiasts –including Zucker senior- pose during the show. He informs us he has worked for six years on this project. Does typing out radio interviews really take that much time ? Around Corelli’s opinion of older and sometimes more recent singers (especially Pavarotti and Domingo) Zucker has built some chapters on 19th century stars and on Italian tenors of the past where a few Corelli comments come in handy. With the exception of Jewish-American Richard Tucker, Polish Jean de Reszke and Spanish Placido Domingo only great Italians are discussed and not French-Italian singers like Luccioni, Micheletti, Vezzani (Corsican is in reality an Italian dialect). Maybe Corelli had scant knowledge of them. For money’s value Mr. Zucker adds a detailed chapter on the way most of the aforementioned tenors recorded the role of Radamès which they all had in common (Trovatore could have been done as well; luckily without Vickers) and adds a small but interesting chapter on “the fluctuating fortunes of vibrato” .

Mind you, I’m not suggesting that the whole book is trash; just that it is a rehash of well-known radio tapes with some additional pages. With a stern editor maybe (very much maybe as Zucker belongs to the category of “I always know best”) something could have been made out of this jumble of facts and opinions but I fear the author ‘s personality is somewhat contrary to systematic streamlined contents. Nevertheless there are some flowers blooming in the chaos. The book is published on fine, heavy paper. It is full of superb photographs, several already well-known, but in the finest quality possible. You could even buy the opus justfor the many luxury ones. Moreover Mr. Zucker does know something on singers and vocal technique and the material he discusses and one immediately realizes the care Zucker has taken on getting the spellings etc 100% correct. As already implied this publication has no real theme and comes across as unfocused. Nevertheless there is a redeeming feature. I would advise prospective buyers to read it as a series of rather loosely connected articles. Say: Zucker with and without Corelli on interesting tenor’s careers and singing methods. One article each evening before going to sleep and it will probably work well. The chapters on 19th century singing and someone like Lauri-Volpi who followed the old traditions -killed off by Caruso and his successors- are very enlightening. So are the many references to vocal production though I fear the discussion can be technically difficult to follow. Even more bewildering; for every example of “covering” Zucker offers examples of tenors who don’t follow the rules and still had world careers. The same can be said for the long discussions on lowering the larynx (Del Monaco), floating the larynx (Corelli) or not using that technique at all.

Zucker (and sometimes Corelli too) has rather inconvenient opinions. Few belcanto lovers will agree with both men that Gigli was at his best after 1937. The late Rodolfo Celetti, Italy’s best known vocal critic, wrote in the complete Italian Gigli-Voce del Padrone-series that the tenor’s voice markedly declined from that year on. Still Zucker has a point when he stresses the new found dramatic impetus in the tenor’s singing. As to pure sound nothing can compare with Gigli’s earlier versions of Chénier’s arias but as a believable character the tenor is more convincing in his 1941 complete recording. By the way don’t believe Zucker for a moment when he writes the tenor became a compelling actor in his movies. Zucker sells Gigli’s movies on DVD and cannot bring himself to declare the tenor was a complete hack hamming his way on in front of the camera. Readers will be surprised too by Zucker’s statements that Caruso is somewhat unmusical while at the same time he acknowledges the superb quality of the voice. Still it is true that Caruso triumphed by virtue of a volume which gave precedence to drama over musical subtlety. The obsession with decibels started with the Neapolitan and continued, except for Schipa who never forced his slender means as for instance Ferruccio Tagliavini did. Sweetness (and maybe less masculinity) took a step backwards. I too have the impression Caruso sometimes was less subtle in his operatic recordings than in his many Neapolitan and Italian songs which sentiments probably touched him more than the hard boiled operatic stuff.

One of the more irritating aspects of the book is the constant habit of Mr. Zucker referring to volumes 2 and 3 where he will delve deeper into the matter. It doesn’t help much when one has to wait for another book before the riddle is solved. In his foreword Mr. Zucker asks for generous donations to continue the good works as “my resources are depleted”. It is true commercial publishers have given up publishing books on opera singers. Still I doubt true benefactors will come forward to help Mr. Zucker telling us in volume 2 when, where and how many times Franco Corelli ejaculated. Maybe the author would do well to restrict himself most of the time to singing. His announcement for a forthcoming biography on Gigli already tells us in detail on his “seven children out of wedlock, his affair with a Jewish woman, his admiration for Hitler, Goebbels, Goering and Mussolini etc”. As a professional historian I can understand the importance of these stories but nevertheless I hope Mr. Zucker won’t forget that Gigli was an operatic singer too. I doubt the slightly maddening construction of this first volume will lead to sales figures that put it on the New York Times weekly bestseller list. Therefore I have the slight inkling that a second and third volume will not appear soon though it shouldn’t take another six years to type out interviews with Bergonzi, Kraus, Alagna etc. or copying the pages of correspondence in the Met archives on the Del Monaco-Corelli rivalry. Maybe Mr. Zucker would do well by simply calling his forthcoming volumes “Conversations with singers on their careers and methods of singing”.

Jan Neckers