University of California Press, 2014, 449 pages; $45.00

GRAND OPERA; The Story of the Met; by Charles and Mirella Jona Affron

University of California Press, 2014, 449 pages; $45.00

[Disclaimer: I knew Charles Affron, not by name then, but as a standee at the old Metropolitan Opera on Broadway and 39th Street in the 1950’s; I met him again a few years ago at the Metropolitan Opera Archives where he was doing intensive research for this book. I have neither a financial or personal interest in the success of this book which I am reviewing, reviewing only because of my own interest in the subject matter].

Over the years there have been several books/studies on the history of the storied Metropolitan Opera: among them were the works of Henry Krehbiel, Irving Kolodin, and Martin Mayer, the last in 1983. These books essentially stop at the management of Schuyler Chapin and therefore do not cover the more recent Joseph Volpe or Peter Gelb regimes. Although the Affrons cover the Met from the theatre’s inauguration in 1883, the distillation of that earlier history is relatively fresh, and they have uncovered several nuggets of information and anecdotes from the earlier regimes that make for a good read. Having observed Charles doing his research, I can testify that he seemingly looked at everything and had access to rare documents. If there is a problem, or rather a challenge, it is that this interesting subject is so vast that the skills needed in condensation and stitching the narrative together are massive. The Affrons developed a formula for the telling of the Met’s story. They break the chronological telling of the Met’s history for paragraphs on interesting related subjects. For example, they have the historic Flagstad debut in 1935 coinciding with the end of the Gatti-Casazza managership, at which point they insert a mini chapter overviewing the careers of Rosa Ponselle and Lawrence Tibbett, two of the great American singers Gatti developed; in Ponselle’s case going back to her pre-Met vaudeville career and the 1918 “Forza del Destino" debut. Great information and good essays, but jarring in the chronological thrust of the book. When they get to the Marian Anderson debut in January 1955 and the breaking of the color line, they insert a long essay on the Met’s checkered history on race relations both in New York and on the national tour in cities that were segregated. It is necessary to explore this issue for its importance in American cultural history and one does learn in this discussion that there was some serious interest in the engagement of the “colored” soprano Caterina Jarboro (born Catherine Yarborough) in the 1930’s, Selika and Aida, of course. (Jarboro enjoyed a significant career in Belgium, where she lived until the outbreak of the Second World War)

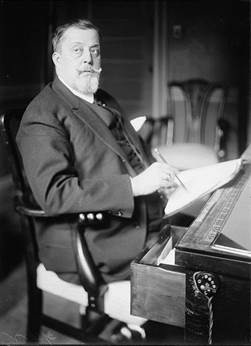

(Gatti-Cassaza and Caterina Jarboro)

(Gatti-Cassaza and Caterina Jarboro)

If one is looking for the Affrons’ “take” on specific singers, the reader is apt to be disappointed. The large index at the back shows, for example, two mentions of Roberta Peters, a singer who holds many Met records, but in fairness Amelita Galli-Curci is only mentioned three times, all in passing, one about her large salary, another about her initial engagement, and a third as a segue to the historic debut of Lily Pons, no estimation of G-C’s vocal or artistic value; Feodor Chaliapin is just one of many illustrious names with no consideration of his art and dominance in and of his special repertoire; there is not even one mention of Margaret Harshaw who not only had a significant Met career, but is a “Met” product (in the paragraph about American singers developed during the War they concentrate on Astrid Varnay and Regina Resnik); and I should mention that the beloved Victoria de los Angeles merits but two mentions, one in reference to being in the 1960 cast of the unsuccessful “Martha” in English. What does this mean? It means that this book is not the place to look for singer information unless that singer is part of a larger theme dealt with in the book, such as production values, opera in English, world wars, financial crises, labor or race relations, PR etc. It is a given that the Met has always been populated by many of the world’s great singers and the Affrons see no need to amplify on their greatness, this is not the mission of this book. If in the current period one wants to know Peter Gelb’s methodology on creating stars, such as Anna Netrebko, there is an informative discussion as to how he has gone about this. He went to Vienna in 2004 and promised her that he would not only make her “a” star at the Met, but “the” star. (page 366 and citation on page 423). In fairness to the Affrons, unlike the previous volumes of Met history, there is now on the Met’s performance database thousands of performances with substantive reviews (metopera.org archives, database}; therefore most readers already know what the critical “take” was on almost any Met artist of interest. In truth, there is not much “new” information “out there” in the world about treasured singers that has not already been told in other forums.

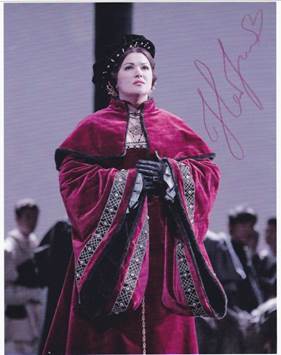

(Margaret Harshaw as Ortrud , what the book is not about, and Anna Netrebko as Anna Bolena, more of what the book is about)

(Margaret Harshaw as Ortrud , what the book is not about, and Anna Netrebko as Anna Bolena, more of what the book is about)

The Affrons’ handling of the Gelb administration is most revealing. They go through all the productions for which Gelb was responsible (except for the Anthony Minghella “Madama Butterfly,” borrowed from the English National and Lithuanian Operas, almost of the productions in his first two years were significantly planned before he became general manager). They give Gelb high marks for his introduction of the popular HD Saturday matinee movie-theatre telecasts in real time from the Met. However, with still secret, incomplete data, the anecdotal

sense is that the HDs only tapped into an already aged, opera-loving existing audience; there is no hard data proving that these accessible movies have built a new, younger audience to love and follow the art form; and after all that was one of the prime reasons given to embark on this expensive adventure. They do suggest in their summation paragraph that the Met’s HDs have reinforced the reputation of the Met at the head of the worldwide opera hierarchy, and for this there is much to praise.

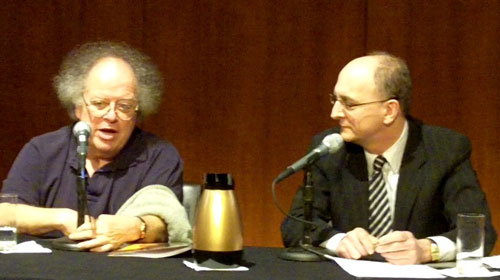

(James Levine and Peter Gelb)

(James Levine and Peter Gelb)

The book has an interesting feature in that for each of the managerships, there is a chart (some taking up to four pages) listing every new work introduced by that manager with dates and statistics. The Abbey and Grau, Conried and Gatti-Casazza regimes naturally introduced the most operas to the Met; the Edward Johnson regime comes off the least innovative, and the Bing regime not that much better. The period from 1975-1990 are considered the James Levine period with Anthony Bliss and others the managers, but Levine as the guiding force. The earlier managers of course were introducing the standard repertory to the institution, and Gatti-Casazza made a point of doing a few contemporary operas almost every season, mostly from the Italian school. Johnson presided over the Met with the war clouds over Europe and then the reality of the War and the post-war situation. Bing was essentially conservative about the repertory and in his twenty-two years premiered only a few new works. There are “on-point” photographs throughout the book, poorly reproduced for the most part, not on photo paper, but inserted at relevant portions of the text.

(Bing surrounded by Callas and Mario Del Monaco)

(Bing surrounded by Callas and Mario Del Monaco)

Even with all the deficits mentioned above, this is still a good distillation of Met history and is a good “read.” The prose style is appropriate to the subject matter and the Affrons met the basic challenge of presenting an interesting and comprehensive telling of the the theatre’s history; this book is not a new regurgitation of vocal art showcased by the Met.

Charles Mintzer